Commentary by Sean Cavanaugh MD, Associate Editor, Clinical Correlations

Commentary by Sean Cavanaugh MD, Associate Editor, Clinical Correlations

A 51-year-old man with a history of DVT diagnosed seven months ago presents to your clinic for follow up. He has no family history of blood clots. He has been on coumadin since his DVT was diagnosed. No testing for thrombophilia has been done. How do you proceed?

Recently, The Annals of Internal Medicine released an excellent statement about the treatment of venous thrombosis (see prior post). Unfortunately, it does not address the more interesting questions of how and why we would evaluate a patient further for hypercoagulability and risk of recurrent DVT.

There is a general consensus that patients with the following disorders have a higher risk of recurrence and should have long-term anticoagulation:

1. Antiphospholipid syndrome: (APS)

A. Anti-cardiolipin antibodies: antibodies against lipid complexes.

B. Anti-Beta 2 glycoprotein I

C. Lupus anticoagulants: A reproducible lupus anticoagulant assay (documented positive assay one more than one occasion)

** Evidence suggests that LA and anti-Beta2 are more thrombogenic than the other anti-phospholipid antibodies

2. Antithrombin III deficiency (and, to a lesser extent, Protein C and S deficiency)

3. Homozygous factor V Leiden (R506Q)

4. Cancer

5. Compound heterozygous factor V Leiden (FVL) PLUS and prothrombin 20210a mutation carriers (Not much is known about the increased risk of homozygous prothrombin gene mutation but it presumably belongs in this category.) Patients who are heterozygous for Factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210a have lower odds rations for recurrent DVTs. Many physicians do not recommend testing for these conditions after an initial DVT under routine circumstances.

It is generally recommended to test for antiphospholipid antibodies and to do an age-appropriate cancer work-up in patients who have presented with an unprovoked DVT.

The patients for whom you might consider a genetic thrombophilic workup include:

- Age <45, any venous thrombosis (the age is arbitrary and variable amongst experts).

- Venous thrombosis in unusual sites (such as hepatic, mesenteric, and cerebral veins – and here you would consider an even broader w/u for myeloproliferative diseases, PNH).

- Recurrent venous thrombosis.

- Venous thrombosis and a strong family history of thrombotic disease.

- Venous thrombosis in pregnant women or women taking oral contraceptives.

- Relatives of individuals with venous thrombosis under age 50.

- Myocardial infarction in female smokers under age 50.

In a broad population of patients without cancer and an initial unprovoked DVT, we know that after discontinuation of coumadin, the cumulative recurrence rate is up to 30 % over the next ten years. Men have a recurrence rate of 25.3% after 7 years and women have a recurrence rate of 9.9% after 7 years. Being able to identify who is at increased risk for recurrence MAY help us make better treatment decisions. There have been a number of articles published on easy tests that might help us discriminate:

1. Patients with an abnormal D-dimer level 1 month after the discontinuation of anticoagulation have a significant incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism, as compared to patients with normal D-dimer level. (15% vs. 6.2% after only 1.4 yrs; adjusted hazard ratio was 2.27). Palareti G, et al., NEJM. 2006 Oct 26; 355(26): 1780-9. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/355/17/1780 The negative predictive value of D-dimer was 92.9% and 95.8% in subjects with an unprovoked qualifying event or with thrombophilia, respectively. Palareti G., et al. Circulation. 2003; 108 (3):313-8. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/108/3/313

2. Patients with thrombin generation less than 400 nM had a 60% lower RR of recurrence than those with greater values (RR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.27-0.60; P<.001). JAMA 2006; 296 (4): 397-402. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/296/4/397

3. Measurement of APTT as a ratio to reference normal range allows stratification of patients with VTE into high- and low-risk categories for recurrence. (patient with ratio > or equal to .95 had a .56 relative risk of recurrence compared to pts with ratio <.95). Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2006; 4 (4):752-6.

4. Residual thrombosis on ultrasound has a hazard ratio of 2.4 for recurrent. Prandoni P et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Dec 17; 137 (12):955-60. http://www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/137/12/955.pdf

In summary, D-dimer, APTT and thrombin generation all evaluate clot activity. Therefore, it makes sense and is more economical to just check one of the three. If that test is abnormal, then proceed with the hypercoagulation work-up. Patients (particularly male patients) with a positive finding on the above-mentioned tests have upwards of a 30% risk of recurrence over 10 years after stopping anti-coagulation. Patients without these risk factors probably have less than 10% risk. Your decision to stop coumadin should include your assessment of the patient’s hypercoaguable state and then consideration of all the other well-known factors that affect the ability to anti-coagulate.

For this patient – a test for anti-phospholipid antibodies is warranted, as well as an age-appropriate cancer screen. If both are negative, his risk can be better assessed with a D-dimer and/or an ultrasound a month or so after stopping the coumadin.

In the absence of D-Dimer elevation or U/S findings his risk of recurrence over the next ten years may be closer to 10% – and a good conversation about his risk aversion should be had with the patient.

If either is abnormal, then his risk for recurrence may be as high as 20+% over the next decade (if he were female, that risk would be substantially lower). And, if there are no contra-indications, then it would be advisable to continue treating. Of course, the patient always has to be able and willing to commit to the life-style changes required.

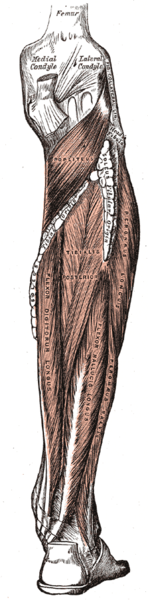

Image from Gray’s Anatomy, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons