Commentary by Timothy Wong, MD

Commentary by Timothy Wong, MD

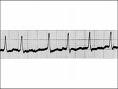

A group of short articles focusing on the consequences and management of atrial fibrillation (AF) recently appeared in the July 7th issue of the Health section of the New York Times. In brief, the articles highlighted the risks of thromboembolism, the lack of very successful medical therapies, and the growing demand for catheter-based atrial fibrillation ablation procedures.

As a cardiology fellow on the consultation service at a teaching hospital in western Pennsylvania, I find that atrial fibrillation is perhaps the most common reason for consultation. I would like to share a brief overview of an approach to atrial fibrillation management and also clarify some points discussed by the articles.

There are several questions that should be answered when seeing a patient in consultation for atrial fibrillation:

1) Is the atrial fibrillation paroxysmal or persistent?

2) Is the patient symptomatic from the arrhythmia?

3) Is a rate control or a rhythm control strategy recommended?

4) Is aspirin or warfarin for stroke prophylaxis recommended?

For the purposes of this discussion, AF in the context of valvular heart disease or reversible causes (e.g. hyperthyroidism, acute myocardial infarction, the perioperative period, etc.) is excluded.

Let’s start off with some definitions. According to the 2002 American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association / European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation, the definition of paroxysmal AF is atrial fibrillation that self terminates, usually within 24 hours. Persistent AF continues for more than 7 days without termination. Permanent AF describes atrial fibrillation persisting for 1 year in which cardioversion has not been attempted or has failed. Accurately classifying the patient into the above categories is important because the groups have varying success rates with catheter based ablations. A good history and physical examination will usually reveal whether or not a patient is symptomatic from the atrial fibrillation.

Once the first two questions have been considered, the data can be used to formulate a management strategy tailored to the specific patient. The ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines give suggestions based on the various combinations of frequency and symptoms. In general, asymptomatic patients may be treated with a rate control strategy using beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers for example. Patients with significant symptoms are often offered a rhythm control strategy, in which pharmacologic or direct current cardioversion is used to convert the patient into normal sinus rhythm, and then antiarrhythmic medications such as amiodarone or sotalol are used to maintain sinus rhythm. If this is unsuccessful, more invasive methods may be considered, including the surgical MAZE procedure, or catheter based ablation. Sometimes, a patient will be offered a rate control strategy on the presenting episode of AF, but later be switched to a rhythm control option if it is too difficult to maintain the rate. The AFFIRM trial demonstrated no survival advantage to a rhythm control versus rate control strategy for persistent AF patients with at least one risk factor for stroke.

Finally, the decision of what type of stroke prophylaxis to offer a patient takes into account the risk of stroke and the risk of the therapy ( i.e. risk of bleeding, compliance, etc.) The CHADS (Coronary artery disease, Heart failure, Age, Diabetes, prior Stroke) score, along with an evaluation for structural heart disease, can help predict the risk of stroke.

With this in mind, my take on the articles in the New York Times is that they may contain a bit too much hype. The risks of atrial fibrillation that were “once thought harmless but now seen as a potential killer” are portrayed as only recently coming to attention of physicians. In fact, multiple studies were published in the 1990’s that brought attention to the ability of anticoagulation to reduce the incidence of stroke significantly, and several review articles in the 1980’s commented on this risk. In addition, surgery is portrayed as “the only proven method to cure many patients”, with catheter based ablations as a less invasive and promising (but not completely proven) alternative. What this opinion fails to mention is that, based on our current knowledge, many patients may not need the cure and can have an excellent quality of life with a very small risk of mortality under the rate control approach. In addition, the success rate of freedom from atrial fibrillation at one year for the catheter-based approach appears to be significantly higher for patients who have paroxysmal versus persistent fibrillation. Rather that reviewing the criteria listed in the FAQ for which hospital to choose to perform an ablation, it may be more worthwhile for AF patients to review with their physician the risks and benefits of a rhythm versus rate control strategy first.

Ultimately, catheter based atrial fibrillation ablation may prove to be a less invasive, more successful modality by which to control this arrhythmia. However, patients and their physicians who pursue this option should first verify that they indeed plan on pursuing a rate control strategy and that first line cardioversion and antiarrhythmic therapy have failed.

Pocket version of the 2002 ACC/AHA/ESC atrial fibrillation guidelines:

http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1017094776302AF_pktguideline.pdf

The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:1505.

Kannel, WB, Abbott, RD, Savage, DD, McNamara, PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1982; 306:1018.

Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study: Final results. Circulation 1991; 84:527.

Wolf, PA, Abbott, RD, Kannel, WB. Atrial fibrillation: A major contributor to stroke in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1987; 147:1561.

Wolf, PA, Abbott, RD, Kannel, WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke 1991; 22:983.

Wyse, DG, Waldo, AL, DiMarco, JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. The atrial fibrillation follow-up investigation of rhythm management (AFFIRM) investigators. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1825.