Commentary by Howard Leaf, M.D. Assistant Professor, Division of Infectious Diseases and Immunology

Commentary by Howard Leaf, M.D. Assistant Professor, Division of Infectious Diseases and Immunology

Pressure continues to build for healthcare facilities to act to decrease hospital-acquired infections, particularly those associated with MRSA. This is partly data-driven, with one study reporting that 25% of patients acquiring MRSA colonization during a hospitalization subsequently become infected [1]. The call to act is also partly a political response to concerns in the lay press about “superbugs” wreaking havoc both in hospitals and in the community. Seven states have either passed legislation or are considering bills to mandate admission screening cultures (ASC) for MRSA. Some restrict the mandate to ICUs; others do not.

The evidence basis for decisions as to how best to address MRSA in hospitals is growing, although no response is accepted by all. One of the more contentious issues is the value of admission screening cultures to identify colonized patients who may then be isolated and perhaps decolonized. The debate continues as many trials, some with conflicting results, are reported from different settings, utilizing various combinations of interventions (e.g., rapid PCR-based vs. agar culture-based screening, decolonization vs. no decolonization), with non-uniform endpoints (e.g., transmission rates vs. infection rates). Thus a consensus has not developed. Last month a systematic review of 20 relevant papers published through September 2007 was reported in Clinical Infectious Diseases [2]. The authors conclude that “the overall quality of the evidence is poor; thus, definitive, evidence-based clinical recommendations cannot be made.”

Two studies have since been reported and are widely cited. In March, JAMA published the results of a Swiss study examining 21754 surgical patients assigned either to ASC and contact isolation, with decolonization and adjustment of perioperative antibiotics, or to standard infection control, in a crossover design [3]. Rates of MRSA surgical site infection and nosocomial MRSA acquisition did not change significantly in the intervention group, although a low baseline infection rate was noted.

Also in March, the Northwestern University School of Medicine’s 850-bed hospital system reported on its experience, comparing infection rates following the institution of universal screening to historical rates [4]. A 50% reduction in hospital-associated MRSA infections was noted over the 21 months when universal surveillance and isolation was in place. Although decolonization was included as part of the control strategy, adherence to that part of the program was not monitored. Although the reduction in infection rate is impressive, the contribution of the ASC component of the protocol per se needs to be defined. Would screening and decolonization of targeted populations have achieved similar results, at lower costs? Was adherence to standard infection control procedures so substantially improved as to account for a significant reduction in infection rates? Many believe more study is required and that the “one-size-fits-all” approach in different healthcare settings is not appropriate.

While each of the three major NYU teaching hospitals are committed to reducing healthcare-associated infections, their approach to ASC for MRSA differs. While at Tisch Hospital, active surveillance is performed in the 15East ICU, and time-limited surveillance is performed in the Bellevue ICU, the VA performs active surveillance cultures on all admissions to the facility, and on all transfers between wards, as part of a national VA-wide initiative. Whereas both Tisch and the VA place all patients either infected or colonized with MRSA on contact precautions, at Bellevue colonized patients are placed on contact precautions only if a portal of exit is identified. Does this lack of uniformity within the NYU community represent differing views amongst its Infection Control staff? No. Again, these are facilities with different populations, infection rates, and resources. Although favorable cost analyses for ASC have been published [5], hospital-specific factors may tilt the outcomes of such analyses significantly. There are many unanswered questions, and more research needs to be done. As of this writing, the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) 2006 recommendations remain in place, with ASC suggested only when “baseline measures fail” to reduce high MRSA infection rates.

1. Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):776–782.

1. McGinigle KL, Gourlay ML, Buchanan IB. The use of active surveillance cultures in adult intensive care ubnits to reduce methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-related morbidity, mortality, and costs: A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1717–25.

2. Harbarth S, Fankhauser C, Schrenzel J, et al. Universal screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at hospital admission and nosocomial infection in surgical patients. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1149-57.

3. Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Paule SM, et al. Universal surveillance for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 affiliated hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):409-18.

4. Wernitz MH, Keck S, Swidsinski S, Schulz S, Veit SK. Cost analysis of a hospital-wide selective screening programme for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriers in the context of diagnosis related groups (DRG)

payment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:466-71.

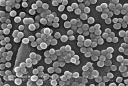

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons, scanning electron micrograph of MRSA

2 comments on “Admission screening cultures for MRSA: Is it time?”

I think there will always be pros & cons to this question. I feel screening will result in avoidable distress to patients. As doctors we need to be very careful how we address this issue.

If 2.4% of children are said to be colonized with this bacteria in their nose and 3 out of 10 adults carry the bacteria in their hand, what difference does it make whether on not we screen them? To surgeons & hospital authorities it may matter. But can we stop other visitors entering hospitals with the bacteria?

We will be soon identifying carriers and advising them to go home with some form of treatment which may or may not work. They are not going to sit in their hame in isolation. Often these patients visit primary care centres with trivial problem, depression and regularly spread the bacteria in the community. They will soon find out that 23% of carriers could die in 2 years.

We must forget our ethics if we advocate universal screening and remember the basic principle of screening is to offer treatment. If we don’t have a treatment to offer, then we must not screen them. Who knows people may live a normal life if the bacteria doen not invade the circulation, so why harm them?

If you don’t screen and isolate infected or colonized patients when they enter the hospital, then you are starting a long line of infections. Number 1 patient (who has not been screened or diagnosed on admission, but is infected) is in a room with Number 2 patient who contracts MRSA pneumonia, he get sick after he goes home, comes back to the hospital and infects whomever is his roommate (Number 3 patient) and any number of healthcare workers he is in contact with and on and on it goes. Somebody has to put a stop to that first infection spreading and doctors know it and so do hospitals.

This exact scnenario happened to my own father who suffers in a nursing home from terminal effects of MRSA pneumonia.

Also, if a person is infected and being admitted for an elective surgery or one that can be postponed, it is always best to try and cure them of colonized MRSA…otherwise they could end up with a chest full of pus or a joint full of pus…it’s disgusting but true. Hospitals would rather just pretend the problem isn’t there, but it is and it can be prevented.

Comments are closed.