I’m surprised I even noticed it. The patient gowns, IV poles, slipper-socks—all normal fare in the hallways of a busy hospital. But down in the elevator bank, just between the Emergency Department and the main hospital floors above us where invariably such sights predominate, he seemed out of place. The stony, oblivious look he carried on his face made my brow furrow just a little deeper, seeing that checked-out expression so characteristic of the over- or under-medicated psychiatric patient.

And then I saw it. Even when it was clear, it took a few moments to put the different pieces of the puzzle together. Spread below him was a thick, murky pool, slightly smeared from the edges of his slippers. It’s always darker than I imagine it will be. Another heavy drop sailing down from the upper gallows of his gown confirms it: this man is bleeding across the floor. I confirm it with a look over to another resident who has put the scene together at about the same time I did, and we both try and engage him. Asking him what floor he came from only brings a group sense of consternation.

“I’m just trying to get a meatball sandwich…”

“Sir, you’re bleeding! You can’t be down here like this.”

The resident, a young Italian woman with an aint-nobody-got-time-for-this look angrily breaks off to activate the Rapid Response Team (RRT), a formal alert that helps bring medical personnel (namely, more overburdened residents) quickly to the site of an emergency. By this time, a member of the hospital police slower lumbers forward with that seen-it-all/don’t-need-to-see-it-again attitude. “Sir, please step over to the side.” Feeling witlessly trapped in the situation, but sorry for this guy – a man in his late 30’s or early 40’s, longer hair, unkempt beard, and despite his protestations, still agreeable enough not to fight with us –I stay on with him, deciding to act as a buffer between him and this guard.

As we slip through a locked door to a secluded hallway behind the elevators, a wheelchair materializes out of the din and we convince him to sit down—in retrospect just trying to sequester his bleeding to his chair rather than sporadically across the floor. The scene still too fresh and his bleeding infrequent enough not to attract too much attention, I try again, just asking for his name this time, and starting with my own. “Kevin” eventually realizes the stir he’s caused, which only increases his frustration, as he sees that his plans for lunch are now lost. “All I wanted was a meatball sandwich,” he echoes in a slow, emphatic rhythm. The RRT arrives, and after a brief period of questioning and a stable set of vital signs, they decide to wheel him over to the ED. As if falling from a tightrope walk of medical care and needing to start again at the beginning, it’s amazing to see how quickly this patient (whose bed is likely still warm upstairs) is turfed away. Fortunately for him, the ED has a similar attitude of intolerance, and seeing him in no crisis and already carrying the physical evidence of someone else’s care (he still had his in-patient bracelet on), they sent him back upstairs. I’m again the witless follower.

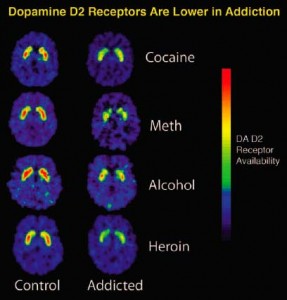

Talking with him on the way up, he tells me how he got to that same ED five days earlier after a heroin overdose in a bathroom. Not sure how long he spent in there, they tell him he went into renal failure (rhabdomyolysis, from what I can gather), and had to spend some time in the MICU. My medical curiosity gets the better of me, and I start asking him about where the bleeding is coming from, and he points to the “tube they pulled out of my crotch”. Less than thirty minutes after they pulled his femoral catheter, the patient got hungry and decided to go on his fateful sojourn downstairs, not understanding or wishing to understand that the pressure dressing required some uninterrupted time to heal. He talked about the low-sodium diet they put him on because of his renal failure, and that between the detox, the feeling of having messed up again, and the shoe-leather food, he couldn’t take it anymore—he needed something to get him through, and that thing was a meatball sandwich. I made a half-hearted attempt to explain why a big sodium load would be dangerous for someone in renal failure (maybe even reviewing the physiology for myself, was I practicing on this guy?), but it fell on deaf ears. That the finer points of renal fluid retention didn’t penetrate his current world view struck me as an appalling lack of perspective, on my part. Without a clear direction to go in after that over-medicalized dead end, I clutched on to the obvious, the immediate.

“Kevin, everything you just told me… Man, you almost died.”

“So what? Like it was so great what I had before? Can’t wait to get back to that,” he spit back with a bitter sarcasm. “What’s the point? I’ve been doing this shit since I was 20, and it hasn’t gotten any better, I’ve just gotten older. I’m over it, man.”

He turned his head away in disgust. I kept mine locked on him, but in that moment I didn’t know what to say. Was he expressing passive, or even active suicidality? Was all this drug use he spoke of just unmanaged depression, or was his grief (appropriately) drawn from his current, dire situation? Should I back off with a few supportive words and call a psych consult? Call his primary team? Was his detox just kicking him pretty hard? In these situations, there’s the naïve conviction that just the right combination of words will turn his hopelessness, will be that spark in the dark that ignites something, that stirs his soul into action, into a changed life. If such words existed, they weren’t available to me at that moment, and so I, too, looked on hopelessly.

After a long pause I asked him if he was hungry. I think he was expecting another moral lecture or pep rally too, because the question caught him off guard. He looked at me hesitantly, and then launched right into a pity-seeking scheme to get that meatball sandwich. “Come on, I just want one sandwich man, how much could it hurt, really?” Even though I felt swayed to just buy one for him in that moment, I thought better and told him I’d see what I could do. After my own escapades sweet-talking the hospital dietary staff, I returned with a full, low-sodium tray. Disappointed, but hungry and gracious enough to accept the gift, he thanked me. I told him I’d come and see him the next day, and I did. We eventually got around to talking about his girlfriend, his shaky job in the food service industry, and his previous experiences in addiction and recovery. At one point he had been sober for over a year. I asked him what he thought was keeping him from getting back to sobriety this time, and he admitted that he could do it again. I asked if I could help, but he declined the offer. Or maybe he had accepted it the day before.

Dr. Jafar Al-Mondhiry is a 1st-year internal medicine resident with NYU School of Medicine

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons