By Jafar Hamid Al-Mondhiry, MD, MA

By Jafar Hamid Al-Mondhiry, MD, MA

Peer Reviewed

A critical care attending once told me that “learning scars” are some of our greatest teachers. And he was right. Many times, a sense of anxiety and rigorous self-criticism has pushed me to improve and develop more than I would have otherwise. This is the natural state of medical trainees: scared to fall behind their well-matched, naturally gifted, and occasionally outright competitive peers; scared to fall short in the eyes of evaluators; scared to stumble in front of patients; scared to not live up to our formidable responsibilities. Spoken or unspoken, this fear is a corroding thread that innervates the medical education experience. It has ruined lives, pushing medical students, residents, and fellows towards depression, burnout, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation.1,2,3 Male physicians commit suicide at twice the national average, female physicians at 3.5 times the national rate.4

Perhaps this is something we carry into medicine, generation after generation of sensitive souls, trying to help others in ways we can’t help ourselves. Poetic as this may sound, we have evidence to believe it isn’t true. A survey of students prior to matriculating to medical school in the US suggests that future doctors experience less depression, burnout, and emotional compromises to their quality of life than their counterparts in comparable professions.5 What happens in the process of training that creates such a tragic shift?

Medical training has origins as old as the art itself, with codes of how to treat aspiring students of medicine written into the Hippocratic Oath.6 However, one could trace the modern story of medical education in the US directly back to the swampy hills of Baltimore, to the fall of 1893 when Johns Hopkins School of Medicine first opened its doors—but only to students who already held undergraduate degrees. A standard unheard of in its time, the school raised its expectations and its curriculum in ways that would define a new era for medical education. The Hopkins model served to elevate the level of medical training above the unstandardized and unrestricted proliferation of proprietary schools popular in the US at the turn of the century, more often interested in making money than making good doctors. Indeed, the famed Flexner Report inventoried the state of medical training for the nation at large in the beginning of the 20th century, and nominated the new Hopkins system as the role model for American medical education.7

Flexner particularly admired the emphasis on basic science and fundamental knowledge demonstrated at Hopkins. The curriculum owed its roots to many of the famed faculty attracted to the new Hopkins experiment, including the technical master and gynecological surgeon Dr. Howard Kelley, the gracious father of bedside medicine Dr. William Osler, and perhaps most importantly the great academic organizer and pathologist Dr. William Henry Welch. But the scientific “learning by doing” and the unapologetic demand for academic excellence was championed by the last member of the “Founding Four”—the surgical genius Dr. William Stewart Halsted. The revolution at Johns Hopkins Hospital demanded that physicians working there take on the dual role of clinician and academic faculty, with full-time responsibility to the medical school. This was an unprecedented system at a time when medical schools simply chartered local physicians to give occasional lectures, and students were left to fend for themselves or hire additional tutoring. It was a shift resisted by many, including Osler himself, but Flexner expressly praised Halsted for his academic entrenchment, stating that “in a real sense, Dr. Halsted was a full-time professor of surgery from the very start.”8

Among the ways one could describe Halsted’s teaching style, the word “brutal” comes to mind. He often waxed on interminably on some narrow topic related to his current research interests, earning his lectures the nickname “shifting dullness.”9 Still, he worked at the leading edge of scientific and clinical discovery, with practice-defining advances in aseptic technique, aneurysm repair, thyroid resection, breast surgery, hernia repair, and intestinal anastomosis. Halsted expected this new batch of minds at Hopkins to meet or exceed him, and when students were called on for an answer, an incorrect response could be met with biting sarcasm or open ridicule. From his students he culled candidates for his surgical residency program—the first in the world and a highly influential model for the academic surgery to follow, with greats such as Harvey Cushing directly indebted to Halsted’s mentorship.10 As the longest witness to Halsted’s academic trials, surgical resident John M.T. Finney sums up Halsted’s approach appropriately: “To the good student, he was a great stimulus, to the poor one, a constant terror.”11

Dr. Halsted expected his students and residents to take on research topics in the lab and produce original work, after his own fashion. Halsted himself, however, did not learn these techniques or take this focus until coming under the auspices of Dr. Welch’s care and tutelage. This he did not of willing interest, but because of his own troubled past. At one time a leading surgeon in his native New York City, Halsted fell from a high position of surgical authority – operating at Bellevue, Roosevelt, and several other major New York hospitals – under the weight of one of his own great discoveries: cocaine anesthesia. Halsted caught word of the topical use of cocaine from the German medical literature, and in true pioneering fashion immediately took to experimenting with the drug, not only in the operating room but on himself, his colleagues, and even his medical students. In the process, Halsted developed a devastating addiction to intravenous cocaine that eventually engulfed his professional medical life in New York, leading to exile, long-term hospitalization, and, in an ironic twist, a persisting addiction to morphine during the course of his treatment for cocaine dependence.11,12

It was under these dire conditions that we received the Halsted of Hopkins, the man who would later command many of the developing features of this new medical education system. His exile from surgery upon arrival to Baltimore pushed him out of the operating room and into the laboratory, where his only subjects were the stray dogs of Baltimore. Ample evidence from several recent historical inquiries suggests that Halsted persisted in his addiction throughout his Hopkins tenure, undergoing repeated hospitalization, frequent absences from the OR , and even at one point falling under the medical care of Osler himself for opiate withdrawal. 13

Dr. Halsted’s transformation in Baltimore was extraordinary, and it is with historical perspective that we see the guiding hand of addiction in his attitude and behavior. The Halsted of New York was a dedicated educator, a masterful and highly sought-after tutor and quiz designer. Dr. Charles A. Powers, one of Halsted’s former students, recalled his experiences with his New York “quizmaster” in a eulogy to him, remarking that “his patience, steadiness, diligence and above all, his thoroughness, brought out the very best there was in those who were in contact with him.”14 A fellow New York tutor Dr. Lucius Hotchkiss claimed, “he was always ready to help the boys with their work and was very pleasant with them.”15

Opposite to this in every way, was the Halsted of Hopkins: reclusive, hostile, and austere. Where he once was a bold, ambitious, and charismatic operator on the New York scene, in Baltimore Dr. Halsted withdrew more and more from the operating room and into his research work—a transition that would have prolific implications for the advancement of surgery in the early 20th century. As a suffering drug addict, he had a clear reason for preferring the more lenient setting of the laboratory. It was a space of inquiry and even genius, but one that came at the expense of patient care, teaching, and human fellowship.16 Unable to maintain true intimacy with any in Baltimore out of fear of discovery, Halsted was forced to live a life of profound dishonesty, and pushed all his energy into what he felt he could control—his academic work. One can see his obsessive mental pathology in the way he addressed a new class of surgeons, discouraging them from a life of meaningful community service in favor of scientific work:

Public spirited men, those who concern themselves deeply with the immediate welfare of their friends and fellows, who respond eagerly to every call for assistance and strive to perfect themselves for the work that the day may bring forth, have not the time for the prolonged concentration required for the framing and solving of new problems.17

George Heuer, one of his former residents, recalled that Halsted “reminded me more than once that if I aspired to be the head of a department I must make up my mind to forego many pleasures in life.” He even advocated that surgeons should forgo marriage altogether. Halsted shunned what few friends he had, avoided his patients, residents, and even his own wife. Heuer plainly sums up Halsted: “Altogether, in relations to his colleagues, he seemed a lonely figure.”18

Halsted died in 1923, ironically of cholangitis, a disease he made great surgical advances treating during his lifetime. Much has passed between his age and ours, and the pathology of a whole medical culture can hardly be attributed to one man. But Halsted is the ghost of our academic strivings as young medical careerists, the quintessential example of the way we can search, struggle, and succeed professionally, and yet fail in our pursuit of a balanced life. It is the compromise we all must face, but the halls and memories of history will be filled with figures of great professional and scientific achievement at unknown personal costs, costs often erased or forgotten, and so we adapt these role models with naïve passion and inevitable pain.

William Stewart Halsted is likely the single greatest scientific contributor to surgery in American history. In remembering his life, we must consider what was lost in the pursuit of medical greatness—both personally and by our patients. Osler emphatically believed that the obsession with laboratory sciences and technical mastery placed the whole enterprise of medical education in jeopardy, stating powerfully: “To have a whole faculty made up of Halsteds would be a very good thing for science, but a very bad thing for the profession.”19

Dr. Jafar Hamid Al-Mondhiry, MA is an internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Medical Center

Reviewed by Dr. David Oshinksy, Medical Historian and Director of the Division for Medical Humanities at NYU School of Medicine.

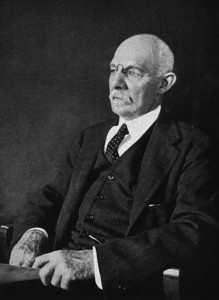

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24448053

- Berge KH, Seppala MD, Schipper AM. Chemical dependency and the physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):625-631.

- Bright RP, Krahn L. Depression and suicide among physicians. Curr Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):16-30.

- Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, Lonnqvist J. A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(3):274-279. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8833679

- Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520-1525. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25250752

- Hippocrates. “… to teach them this art–if they desire to learn it –without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath.”

- Ludmerer KM. Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Crowe SJ. Halsted of Hopkins: The Man and His Men. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1957: 236.

- Bliss, M. William Osler: A Life in Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999: 215.

- Dr. Noland Carter, a former surgical resident under Halsted, calculated that of the 17 residents to fully graduate from his system, 11 set up similar residencies in other academic medical centers, which by 1952 would go to train a total of 238 surgeons. Carter, BN. The fruition of Halsted’s concept of surgical training. Surgery. 1952;32(3):518-527.

- Imber G. Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of William Stewart Halsted. New York, NY: Kaplan; 2010:192.

- Markel H. An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. New York, NY: Random House; 2011.

- Osler W, Bates DG, Bensley EH. The inner history of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1969;125(4):184-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4903725

- Powers C. The Passing of a Distinguished Surgeon. Colorado Med, 1922, xix (no. 10): 195. In: The William Henry Welch papers. Box 23, Folder 32. Baltimore: The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

- Heuer GJ. Dr. Halsted. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull.1952;Supp 90:16.

- His withdrawal from clinical life was so complete that his obituary in Science states plainly, “he spent his medical life avoiding patients.” From: William Stewart Halsted, 1852-1922, Science. 1922;56(1452): 461. (Note: obituary, signed only with “H.C.” likely written by Harvey Cushing)

- Halsted WS. Dr. Tiffany’s place in American surgery. In: Burket W, ed. Surgical Papers by William Stewart Halsted, vol. 2. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press; 1922:509.

- Heuer, 33.

- Osler W. Letter to George Dock, 1912. In: Cushing H. The Life of Sir William Osler, vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1925:335.

One comment on “Mental Pathologies at the Root of Modern Medical Training: Lessons from the Life of Professor William Stewart Halsted”

If only William Osler’s preference for practical clinical medicine over that of rigorous scientific medicine (the probable bias of Halsted) had been adopted in early medical schools, modern medicine might have developed along more humane lines.

Comments are closed.