By Dorice L. Vieira M.A., M.L.S.

By Dorice L. Vieira M.A., M.L.S.

Faculty Peer Reviewed

The title to this feature may seem a bit odd, but there is a proper way to ask evidence-based clinical questions. “What is the treatment for diabetes?” is not a well-defined question. A PubMed literature search using the terms “diabetes” and “treatment” retrieves a total of 167,843 citations covering a myriad of approaches to the treatment of diabetes: type I (26,884 citations) or type II (35,368 citations), patient satisfaction (1,449 citations) and guidelines (2,723 citations). Using PubMed’s “Clinical Queries” search feature, which applies an evidence-based literature search filter, does not yield significantly better results than the original total–9,456. “How effective is inhaled insulin in the treatment of type II diabetes in adolescents?” is an example of a well-defined clinical question.

The most effective way to generate a potentially answerable clinical question is to base your questions directly on the patient scenario. There are two types of questions that arise from the patient scenario, background and foreground questions. Background questions are simple questions which help clarify information about a disease condition or possibly a diagnostic test. What are the current anti-hyperglycemic therapies being used in the treatment of diabetes? Or, what is the mechanism of action for metformin? These questions are easily answered using a print or electronic textbook. General review articles can also be useful when clarifying basic questions.

Questions determining the efficacy of therapy, agents that may cause harm, differential diagnosis/diagnostic tests and a patient’s prognosis, are four representative types of foreground questions that are most often generated from a patient’s case and will be the focus of this feature. The type of clinical question is determined by the patient case scenario being presented, “In a 62 year-old female with right lower quadrant pain, does the absence of fever rule out appendicitis?”—Thus, you have a question of diagnosis.

Simplified Clinical Scenario

A 42 yo woman presents with type II diabetes. She is on metformin , 500 mg bid. You had recently read that she may be at risk for fatal lactic acidosis.

You ask: In an adult patient with type II diabetes, what is the risk for fatal lactic acidosis associated with metformin? — Thus, we have a question of potential harm. (Note: an alternative is to fill in the table below and then generate the question.)

The characteristics of the case fit into a formula known and PICO, P (patient, problem or population), I (intervention), C (comparison or control), O (outcome). From the patient case, simply fill in the boxes:

| P | I | C | O |

| 42 yo woman (adult)Type II diabetes | Metformin | (none) It is possible to compare metformin against placebo or other therapies if your clinical question calls for a comparison | Prevention of fatal lactic acidosis |

By stating a “well-defined clinical question” and completing the PICO formula, you can now effectively and efficiently search the primary and secondary bibliographic databases.

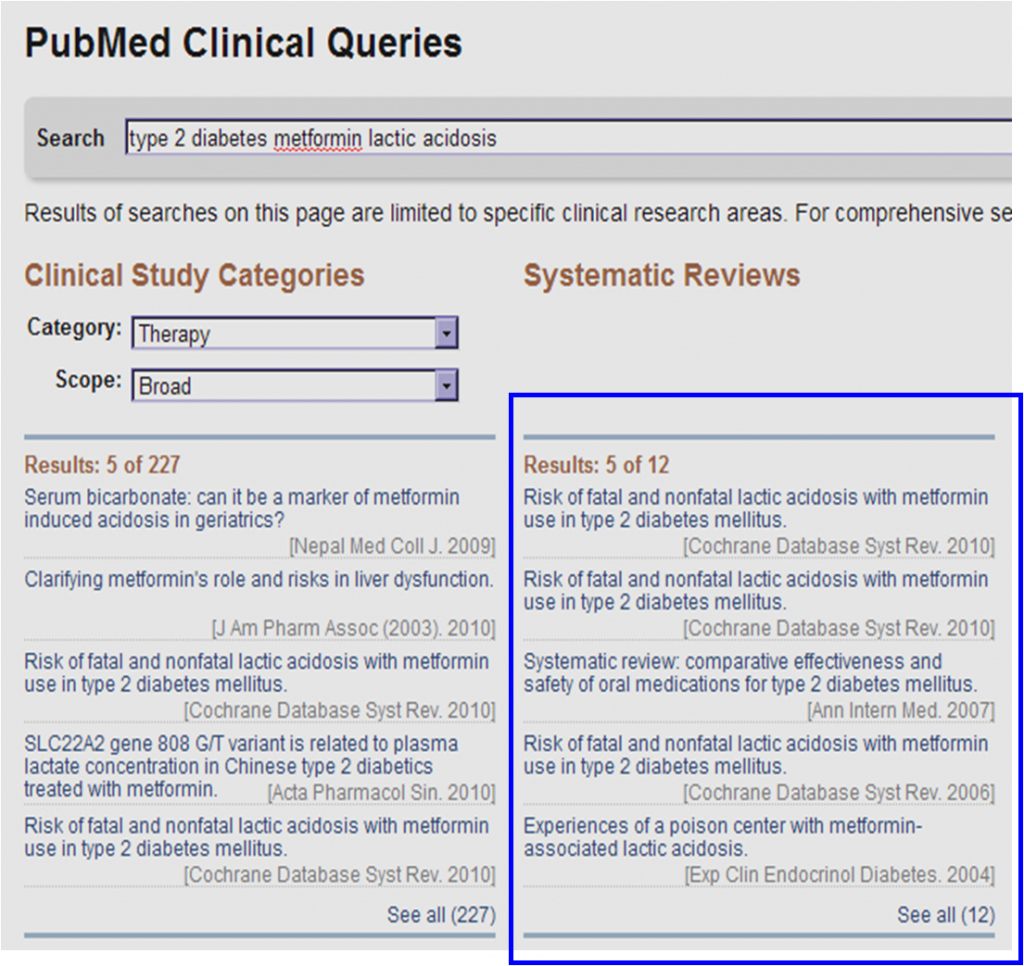

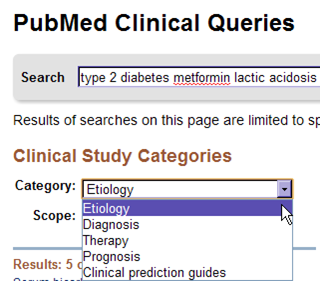

A PubMed “Clinical Queries” search using the terms type II diabetes, metformin and lactic acidosis, listed as separate concepts, retrieves ten systematic reviews, one of which is a Cochrane Library systematic review that has been updated three times (currency and accuracy is a primary objective for Cochrane).

PubMed converts the search as follows, translating keywords in the appropriate Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) when possible. It also applies a filter which includes systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of clinical trials, evidence-based medicine, consensus development conferences, and guidelines.

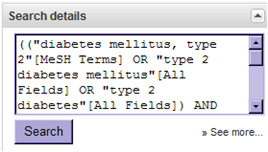

((“diabetes mellitus, type 2″[MeSH Terms] OR “type 2 diabetes mellitus”[All Fields] OR “type 2 diabetes”[All Fields]) AND (“metformin”[MeSH Terms] OR “metformin”[All Fields]) AND (“acidosis, lactic”[MeSH Terms] OR (“acidosis”[All Fields] AND “lactic”[All Fields]) OR “lactic acidosis”[All Fields] OR (“lactic”[All Fields] AND “acidosis”[All Fields]))) AND systematic[sb]

The search strategy can be found in the “Search details” box on the right side of the PubMed screen results.

The search strategy can be found in the “Search details” box on the right side of the PubMed screen results.

And the evidence shows . . .

Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Metformin, a medication used to lower glucose levels in patients with diabetes mellitus, has long been thought to increase the risk for a metabolic disorder known as lactic acidosis. This review summarised data from all known comparative and observational studies lasting at least one month, and found no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in 59,321 patient-years of metformin use, or in 51,627 patient-years for those not on metformin. Average lactate levels measured during metformin treatment were no different than for placebo or for other medications used to treat diabetes. In summary, there is no evidence at present that metformin is associated with an increased risk for lactic acidosis if prescribed under the study conditions. (Realize that in the majority of studies patients with multiple comobidities and at higher risk of side effects of the study drug/procedure are usually exluded. Thus the consclusions that are drawn regarding safety apply only to the study conditions and inclusion criteria of the patients-ed.)

The biomedical bibliographic databases are great but are only effective when you take a systematic approach to searching them. Take a few moments generating well-defined clinical questions generated from a PICO table, search PubMed’s Clinical Queries, and review your results. Will you encounter problems? Yes. No system is perfect. If you are having problems or want to make sure that you have conducted a comprehensive search, please remember to consult a Public Services Librarian for assistance. Faculty librarians are skilled in obtaining the highest level of results from a wealth of resources and well as in teaching you how to search the various biomedical databases offered by the NYU Health Sciences Libraries!

Dorice L. Vieira M.A., M.L.S. is an Associate Curator NYU Health Science Library

Peer reviewed by Neil Shapiro, Editor-In-Chief, Clinical Correlations

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons