Peer Reviewed

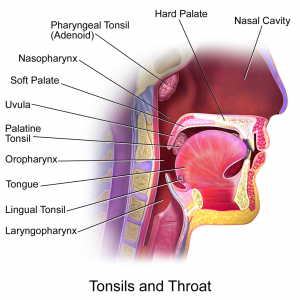

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is relatively rare but incidence has increased in the US over the past 40 years. [1] Tonsillar cancer is the most common type of OPSCC followed by base of tongue cancer, which together account for 90% of all OPSCCs.[2] The incidence of both tonsillar and base of tongue cancers individually have also increased in the US.[3] OPSCC is more common in men than women and smoking and alcohol are well known risk factors for it.[1,4] However, the increased incidence in the US has not seen a parallel rise in smoking and alcohol consumption.[5] This implies some other factor may be responsible for epidemiologic changes in OPSCC rates.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted disease in the US and can cause cervical, vulvar and anal cancer.[6] HPV exists in over 100 types and is found in skin and mucosal tissue. It is strongly associated with OPSCC, especially of the tonsils and base of tongue.[5] As OPSCC, tonsillar and base of tongue cancer have increased in incidence, the proportion of HPV-positive OPSCC has also increased.[2,5] By one estimate, the percent of HPV-positive oropharyngeal tumors increased from 16% in the 1980s to 73% in the 2000s[1] while multiple other studies support these findings.[7,8] In addition, the absolute number of HPV-positive cancers has increased while it has declined for HPV-negative cancers. This decline in the number of HPV-negative OPSCCs parallels a decline in smoking in the US.[1] Detection of HPV DNA in OPSCC varies widely; from 25% in some studies to 100% in others.[2,9,10,11] This may be due to the variety of tumor sites studied, techniques used for detection and how long before the sample was tested.[2] For tonsillar cancer specifically, one study estimated HPV to be present in 40-60% of cases in Western cultures.[12] Thus, there is a significant epidemiologic connection between HPV and OPSCC.

A role for HPV in OPSCC pathogenesis is also supported by molecular findings. In certain high risk types of HPV, E6 and E7 proteins made by the virus can deregulate the cell cycle by preventing the normal function of p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) protein respectively.[2] As an example, HPV-16 DNA is a risk factor for tonsillar cancer and the oncogenes E6 and E7 are generally expressed in HPV-positive tonsillar carcinoma.[5] There is also an association of p16 over-expression with HPV-positive OPSCC, an indicator of E7 inactivating Rb which in turn upregulates p16.[2] HPV-positive tumors infrequently have mutated p53 and often show chromosome 3q amplification (similar to that in HPV-positive cervical and vulvar cancer).[2] Conversely, p53 mutations in OPSCC are associated with alcohol and tobacco use.[13] HPV-positive OPSCCs occur at younger ages and are less likely to have a history of alcohol or tobacco use compared to HPV-negative OPSCCs.[3] Interestingly, this evidence suggests that HPV and smoking or alcohol are molecularly distinct etiologies of OPSCC.

Reported prevalence of oral HPV in individuals without OPSCC is highly variable. Despite this uncertainty, incidence rates for tonsil and base of tongue HPV infection are increasing in recent years and birth cohorts.[3] In one study, high risk HPV types were found in the oral cavity of 4.5% of HIV-seronegative and 13.7% HIV-seropositive individuals, with HPV-16 the most common type.[12] The increased rate found in HIV-seropositive individuals may be due to abnormal oral mucosal immunity resulting from HIV infection. Also, oral HPV infection in both groups was associated with HSV-2 seropositivity, a marker of sexual behaviors. In the HIV-seropositive group, oral-genital contact was associated with oral HPV infection.[12] Other studies have shown that a high number of oral sexual partners, young age of first intercourse and increased number of open-mouth kissing partners were associated with HPV infection.[14,15,16] Furthermore, markers of high-risk sexual behavior has increased in recent birth cohorts.[3] Therefore, increasing HPV infection rates are likely a result of changes in sex practices.

Not surprisingly, risky sexual behavior is also a risk factor for HPV-positive OPSCCs.[1,13,14] Patients with a history of oral-genital sex are more likely to present wtih an HPV-positive OPSCC when compared to those without such history.[5] In men, risk of OPSCC increases with age of first intercourse and increasing number of partners.[5] Interestingly, the combination of current cigarette use and HPV-16 seropositivity is associated with additional risk of OPSCC beyond what would be expected by summing the individual risks alone.[13] One hypothesis is that HPV induces an immune response and that smoking abates it.[2]

Considering the evidence, it seems clear that recent changes in sexual behaviors increase the risk for oral HPV infection and have led to the observed increase in OPSCC. If trends continue, by 2020 the number of HPV-positive OPSCCs is expected to surpass the number of cervical cancers in the US.[1] Unfortunately, the potential of the HPV vaccine to prevent oropharyngeal infection has not yet been conclusively demonstrated. A double-blind controlled trial did show significantly fewer oral HPV16/18 infections in women four years after receiving the bivalent vaccine compared to those who did not.[17] However the study was limited in that baseline HPV prevalence was not assessed. The vaccine is effective in preventing cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile and anal infections suggesting it would be comparably effective for oropharyngeal infection and by extension, OPSCC. Regardless, these epidemiologic trends are strong enough to warrant not only HPV vaccination of preteen males and females as is currently recommended by the CDC, but also to inform safe sex counseling and screening for cancer risk factors for all patients.

Dr. Tyler Litton a former NYU medical student is a current radiology resident at Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Howard Leaf, MD, Medicine, NYU Langone Medical Center

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294-4301. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21969503/

- Ramqvist T, Dalianis T. Oropharyngeal cancer epidemic and human papillomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(11):1671-1677. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21029523

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and –unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):612-619. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18235120

- Licitra L, Bernier J, Grandi C, Merlano M, Bruzzi P, Lefebvre JL. Cancer of the oropharynx. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;41(1):107-122. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11796235

- Hammarstedt L, Lindquist D, Dahlstrand H, et al. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(11):2620-2623. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16991119

- Anic GM, Lee JH, Stockwell H, et al. Incidence and human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution of genital warts in a multinational cohort of men: the HPV in men study. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(12):1886-1892. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22013227

- Mehanna H, Beech T, Nicholson T, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer–systematicreview and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013 May;35(5):747-55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22267298

- Näsman A, Nordfors C, Holzhauser S, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus positive tonsillar and base of tongue carcinoma: a stabilisation of an epidemic of viral induced carcinoma? Eur J Cancer. 2015 Jan;51(1):55-61.

- Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Doody DR, et al. Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(21):1626-1636.

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):24-35.

- Mehanna H, Franklin N, Compton N, et al. Geographic variation in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer: Data from four multinational randomized trials. Head Neck. 2016 Jan 8. [Epub ahead of print] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hed.24336/references

- Kreimer AR, Alberg AJ, Daniel R, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in adults is associated with sexual behavior and HIV serostatus. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(4):686-698.

- Gillison ML, D’Souza G, Westra W, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(6):407-420.

- Anaya-Saavedra G, Ramirez-Amador V, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, et al. High association of human papillomavirus infection with oral cancer: a case-control study. Arch Med Res. 2008;39(2):189-197. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18164962

- D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(9):1263-1269.

- D’Souza G, Cullen K, Bowie J, Thorpe R, Fakhry C. Differences in oral sexual behaviors by gender, age, and race explain observed differences in prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection. PLoS One. 2014 Jan 24;9(1):e86023.

- Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 17;8(7):e68329. http://oralcancerfoundation.org/hpv/pdf/Oral-VE-CVT-2013.pdf