Peer Reviewed

“Wounded healers. It’s a concept…inspired by the story of Chiron, a centaur in Greek mythology who was renowned for his skills as a healer. Chiron was wounded by a poisoned arrow but his immortal status sustained him…He was thus condemned to spend eternity roaming the earth in agonizing pain, healing everybody but himself….the phenomena of depression and suicide among medical students and doctors suggest that we…fit into this archetype. “

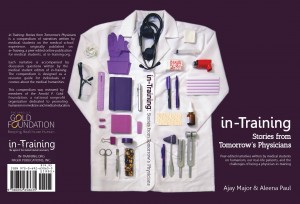

The above selection is an excerpt from a moving essay written by medical student Ajay Koti called “Wounded Healers,” which examines the unacknowledged burden of depression on medical students and physicians. It is just one of many profound essays from a recently published book called In-Training: Stories from Tomorrow’s Physicians, a remarkable compendium of reflective pieces penned by medical students across the country. According to the book’s preface, In-Training was first conceived in 2012 as on online publication where medical students could share reflective pieces about their experiences on the medical wards with their colleagues. The idea struck a chord, and very quickly evolved into a virtual forum of communal experience consisting of over 1000 articles, leading its founders, Ajay Major and Aleena Paul—who are now internal medicine residents—to compile and publish the best pieces in this book through a partnership with the Arnold P. Gold Foundation.

Pieces are organized into themed sections that span the full breadth of the medical student experience in a chronological fashion. It begins with a section entitled “Dissection Lab,” a collection of pieces detailing the overwhelming fear and heavy responsibility that accompanies our first days in anatomy lab, and progresses to other relevant subjects, including “Learning Curve,” a section detailing the agonizing self-doubt and insecurity that comes with being a first-time medical student on the wards, “Systemic Afflictions” which consists of stories focusing on marginalized, vulnerable patients and their interactions with an increasingly complicated health care system and its sociopolitical entanglements, and “Death and Dying,” an emotional collection of essays about students’ first experiences responding to the deaths of their patients. Perhaps most importantly, the sections “Burnout” and “Work-Life Balance” tackle the increasingly relevant issue of physician fatigue and depression, a subject that New York trainees have become all too aware of after several recent, tragic suicides by residents in our city’s training programs.

In addition to the terrific diversity of topics covered by these pieces, the format of the writing is also quite varied, employing poignant short stories, cogent, convincing essays, and beautiful poems to explore its many themes. Each piece is accompanied by several thought-provoking questions posed by one of the editors about the subject matter of the piece that serve as stimulating discussion points for readers. This format makes it easy to use these pieces to spark discussion in a group setting, and I plan to incorporate these pieces and the ‘reading group’ style questions into reflective rounds for my team on a regular basis. The standard of quality across essays is generally high, though there are several middling pieces that could have been trimmed to shorten the book’s length and streamline its overall message.

I started to notice that several authors had multiple pieces published in different sections from various points during their training, and I found myself looking forward to the writings of a few authors in particular. I smiled every time I came across the creatively formatted pieces by Ajay Koti from University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine; I excitedly pored over any essay by Katie Taylor from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai as she consistently explored unique topics with a distinct voice and beautiful, thoughtful prose; and I felt like I was going through the lucidly articulated ups and downs and doubts over a career in medicine along with Jennifer Tsai from the Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University. Featuring multiple pieces by the same author allows the reader to follow the complicated relationship that students develop with medicine as they reflect upon its most uplifting moments and painful lows. This continuity allows the reader to see the evolution of the author over several pieces, making for a more fulfilling reading experience.

I want to take a moment to acknowledge a few of the pieces I found to be truly spectacular in this collection. A highlight is Katie Taylor’s piece “A Wait for the Bus: A Solution for Wandering in Dementia,” which explores a practice employed in Germany where assisted living centers install fake bus stops to prevent their dementia patients from accidentally getting on real city buses and being taken somewhere unfamiliar and potentially dangerous. While this concept seems more at home in a dystopian science-fiction novel than as a meaningful medical intervention, Katie probes the unexpected, humane benefit of this initiative, and writes, “A nurse led [the patient] to the bus stop, and they sat down. They listened to the birds, and felt the afternoon sun. They watched cars go by. Soon, the resident’s panic receded. She forgot why she was there in the first place…in a double negative of amnesia, forgetfulness is the cure for forgetfulness.” She ends by noting how researchers think “the wandering could also be a search for meaning,” and notes so poignantly, “What a testament to the aging human brain, that despite atrophy and invading debris, there perhaps remains a deep, underlying resolve to search for something more…from confusion and non-understanding, springs a search for consequence.” Elsewhere, Jennifer Tsai’s piece entitled “A Lack of Care: Why Medical Students Should Focus On Ferguson” is a standout essay that argues how the appalling death of Michael Brown is a symptom of a larger systemic illness—institutional racism—and contextualizes this tragedy within recent research showing that black patients are more likely to have their pain undertreated in the emergency room compared to white patients, demonstrating that implicit bias is present not only in law enforcement, but in the healthcare system as well. There are scores of other pieces throughout the collection I could mention, and by the time I finished the book, I found myself amazed by the number of earmarks I had made—it was nearly every other page.

NYU has recently implemented a reflective practice curriculum into its internal medicine residency program, and it is, in this writer’s opinion, a most welcome and necessary cornerstone to our training. Unfortunately, the amount of reflective pieces written by residents remains nominal. Even though I am a senior resident months away from completing my training, I drew a tremendous amount of inspiration and strength from this beautiful collection of medical student essays, and I can say that reading it truly changed the way I plan on practicing. I can only hope that residents, including myself, will come to recognize the value of reflecting upon and sharing the stories we become a part of as caregivers for our patients. As Jarna Shah writes in her striking piece “How to Find the Strength to Keep Going,” “I save my stories to remind me to feel in a time when I become so numb.” These stories are a salve to the wounds inflicted by medical training. They are a shoulder to cry on, a hand to hold, a listening ear. It is healing by way of solidarity and shared experience. This extraordinary collection of medical student essays is a remarkable achievement by its many writers and singular editors, and I urge everyone to find a copy and share their own stories—we all emerge from the gauntlet of medical training as wounded healers in our own individual ways, so we would do well to follow Jarna’s advice to “Feel. Remember. And keep going.”

Amar Parikh is a 3rd year internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Medical Center and a Contributing Editor for Clinical Correlations.

Peer reviewed by Neil Shapiro, Editor-In-Chief, Clinical Correlations

Purchase the book here.