By Monica Gupta, MD and Alice Tang, MD

By Monica Gupta, MD and Alice Tang, MD

Peer reviewed

Physician burnout is a phenomenon that is becoming recognized as widespread in both trainees and in practicing doctors. Long taxing hours, insurmountable educational debt, the burden of daily decisions affecting patients’ lives, and the routine sacrifice of self-care are just a few of the factors that physicians identify as causes of their burnout.

What exactly is burnout?

Burnout is assessed across multiple professional fields with the Maslach Burnout Inventory. It has 3 scales that measure emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased sense of personal accomplishment. The first scale, emotional exhaustion, is described as depletion of one’s emotional resources, making one feel unable to “give” any further at a psychological level. The second scale is depersonalization, the development of negative, cynical attitudes and feelings towards one’s clients (in the case of physicians, the patient is the client). This dehumanized perception is further described as one that could lead some to view their clients as somehow deserving of their troubles. The third scale is decreased personal accomplishment, in which people have a sense of futility and do not believe their actions make an impact. Maslach, a social psychologist, observed this syndrome of emotional exhaustion and cynicism to occur in individuals doing “people-work.”1

How prevalent is burnout in physicians?

Physicians are especially vulnerable to burnout because of the nature of the job. Given the need to interact with patients, colleagues, or members of the interdisciplinary care team, physicians constantly have to be “on.” This contributes to burnout at every level of medical training. In a study from the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2002 at The University of Washington, 76% (87 out of 115) of internal medicine residents completing the Maslach Burnout Inventory met criteria for burnout. Furthermore, those who met criteria for burnout were significantly more likely to report providing at least one type of suboptimal patient care at least monthly.2

A 2011 JAMA article from the Mayo Clinic surveying 16,934 residents (74.1% of all internal medicine residents from 2008-2009) demonstrated that 51.5% reported burnout. More significantly, it demonstrated that low quality of life and emotional exhaustion were associated with lower In-Training Exam scores.3

At the attending physician level, a 2012 JAMA original investigation entitled “Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance Among US Physicians Relative to the General US Population” not only compared physicians across medical specialties but also compared them to the general workforce population. It was found that of the 7,288 physicians surveyed, 45.8% reported at least 1 symptom of burnout. Of note, there were substantial differences by specialty. The highest burnout rates were those in the front line of care, specifically family practice, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. The specialties that were found to have the lowest rates of work-life balance satisfaction, which ultimately contributes to burnout, were the surgical fields–general surgery, surgery subspecialties, and OB/Gyn.4 This JAMA study further found that higher levels of education and professional degrees seem to reduce the risk for burnout in fields outside of medicine, whereas degrees in medicine (MD, DO) increase the risk. Compared to a probability-based sample of 3442 working U.S. adults, physicians were more likely to have symptoms of burnout (37.9% vs. 27.8%) and to be dissatisfied with work-life balance (40.2% vs. 23.2%).4

A Medscape 2013 survey found that some of the most common causes of burnout were excessive bureaucratic tasks, spending too many hours at work, and “feeling like just a cog in the wheel.” When comparing men and women, women appeared to be at greater risk of burnout (45% of women versus 37% of men). This may be related to women taking more front line jobs–family practice, internal medicine, and OB/Gyn- as previously described. Interestingly, it was also found that physicians on either end of the age spectrum tended to be protected from burnout, with those 35 and under and those 65 and over with the least burnout.5

Why is this important for us to recognize?

Burnout has adverse effects on both physicians and patient care. Physicians who are burned out have increased rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide. Furthermore, they are more prone to making medical errors and having lower job satisfaction.2,6,7,8 This makes them more likely to retire early, risking patient abandonment and decreased patient satisfaction.9 Ultimately, the rising rates of physician burnout could become a potential threat to successful health care.

So what can we do about this on the institutional level?

Attempts to improve resident burnout through the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) 2011 work hour regulations unfortunately have not demonstrated the intended effect of improving resident wellbeing. A 2015 systemic review in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education reviewed 27 studies and concluded the majority of studies showed either no impact or a negative impact on resident wellness.10

Conversely, other institutional changes such as block scheduling in residency programs are being studied to reduce the rate of burnout amongst trainees. Additional adjustments to the workplace environment by leadership to increase physician control, work place efficiency, and fairness have been shown to decrease emotional exhaustion.11 Lack of feedback and career choice uncertainty are also associated with higher burnout, and as such, increased mentorship by faculty can help reduce burnout in trainees as well.12

Can we teach learners to protect themselves against burnout?

Yes. And it is important to start this practice early in training. Resiliency is “the ability for individuals to respond to stress in a healthy adaptive way such that personal goals are achieved at minimal psychological and physical cost.”13 The concept of identifying protective factors in vulnerable populations was first studied in impoverished children by Garmezy. He found that personality traits and social factors such as temperament, reflection, familial cohesion, parental concern, and external social support allowed these children to thrive despite their environment.14 While some of these factors are innate, studies demonstrate that resiliency skills can be acquired through practice of mindfulness based interventions, positive psychology, and self-care.

The practice of mindfulness allows individuals to have greater awareness of the way stress is manifested in oneself – whether physically or cognitively. This awareness is integral to applying adaptive strategies to avoid propagation of negative thoughts and behaviors that could make one prone to burnout. Several studies have demonstrated improved stress and anxiety levels in medical students after applying mindfulness interventions.15,16,17

A study of brief positive psychology exercises demonstrated a lasting impact on happiness (measured by the Steen Happiness Index) and depression (based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale). The practice of “Three Good Things,” where participants wrote down three things for which they were grateful every night before going to sleep significantly improved happiness and decreased depressive symptoms at 6 months.18 This intervention was studied in internal medicine residents at Duke University School of Medicine and resulted in lower rate of burnout and depression, less conflict, and better work-life balance.19 “Using Signature Strengths in Novel Ways,” was another exercise in which participants identified their top character strengths and used these strengths in novel ways every day for a week–this also produced a lasting effect at 6 months.18

An Archives of Internal Medicine study of 64 combined medicine and pediatrics residents demonstrated that a half-day stress management workshop improved residents coping skills. Participants learned interpersonal skills as well as prioritization of personal, work, and educational demands. Techniques to address self-care, to recognize and avoid maladaptive responses, and to develop positive outlook skills were also offered. This study showed significant short-term improvement in stress and burnout scores as well.20

Where do we go from here?

Ultimately, burnout, physician stress, and workplace satisfaction are important to recognize and address to improve physician well-being and therefore promote better patient care. Ensuring all physicians, including both trainees and attendings, receive instruction in evidence-based self-care techniques to prevent burnout is crucial to the future of medicine. Simply put, if we can’t take care of ourselves, we can’t take care of others.

Dr. Monica Gupta is a fellow in allergy and immunology at University of Virginia School of Medicine and former internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Health

Dr. Alice Tang, MD is an attending physician at Weill-Cornell Medical College and former internal medicine chief resident at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by Barbara Porter MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, NYU Langone Health

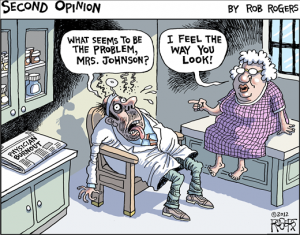

Image courtesy of MDLinks

References:

- Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual.3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358-367.

- West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952-960.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J, and Oreskovich MR. Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance Among US Physicians Relative to the General US Population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-85.

- Packham, Carol. “Physician Lifestyles- Linking to Burnout: A Medscape Survey 2013.” 28 Mar 2013. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2013/public#

- Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(7):1017-1022.

- Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA. 2001;286(23):3007-3014.

- West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071-1078.

- Balch, C. M., Freischlag, J. A., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2009). Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg, 144(4), 371-376.

- Bolster, L., & Rourke, L. (2015). The Effect of Restricting Residents’ Duty Hours on Patient Safety, Resident Well-Being, and Resident Education: An Updated Systematic Review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 7(3), 349–63. http://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00612.1

- Dunn, P. M., Arnetz, B. B., Christensen, J. F., & Homer, L. (2007). Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: Assessment of an innovative program. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(11), 1544–1552. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0363-5

- Ripp, J., Babyatsky, M., Fallar, R., Bazari, H., Bellini, L., Kapadia, C., … Korenstein, (2011). The Incidence and Predictors of Job Burnout in First-Year Internal Medicine Residents: A Five-Institution Study. Academic Medicine, 86(10), 1304–1310. http://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c1236

- Epstein, R. M., & Krasner, M. S. (2013). Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med, 88(3), 301-303. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280cff0

- Garmezy, N. (1991). Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. The American Behavioral Scientist, 34(4), 416.

- Finkelstein, C., Brownstein, A., Scott, C., & Lan, Y. L. (2007). Anxiety and stress reduction in medical education: an intervention. Med Educ, 41(3), 258-264.

- Rosenzweig, S., Reibel, D. K., Greeson, J. M., Brainard, G. C., & Hojat, M. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teach Learn Med, 15(2), 88-92.

- Warnecke, E., Quinn, S., Ogden, K., Towle, N., & Nelson, M. R. (2011). A randomised controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on medical student stress levels. Med Educ, 45(4), 381-388.

- Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. American psychologist, 60(5), 410.

- Sexton, JB. (2015). Essentials for Enhancing Professional Resiliency [Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved from www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/education/7165_GS06.pdf

- McCue JD, Sachs CL. A stress management workshop improves residents’ coping skills. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(11):2273-2277.