Peer Reviewed

Each year around 6 million people are killed by tobacco worldwide.1 Tobacco remains a leading preventable cause of death worldwide.2 From 1965 to 2010, the prevalence of cigarette smoking in the United States has declined from 42.4% to about 19%. This decline is mainly due to public awareness regarding harmful effects of smoking, increase in prices of tobacco products, and implementation of smoke-free policies.3 Despite tremendous strides made in raising public awareness regarding the adverse health effects of smoking and the associated risk of lung cancer, smoking cessation remains a challenge both for physicians and patients. Per a report published by the Centers for Disease Control in 2010, approximately 70% of active tobacco users expressed interest in quitting and about 50% of smokers have attempted to quit smoking. However, the majority of attempts were made without using any available cessation modalities. Additionally, only 3-6% of the smokers who attempted tobacco cessation without any aid remained abstinent 1 year later.2-4

Several pharmacologic therapies are available to assist patients in smoking cessation. These therapies target nicotine, which is the addictive component in tobacco responsible for withdrawal and cravings. Available first line treatment options include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline, and bupropion. NRT is available in various forms—gum, lozenges, spray, patches or inhaler. The goal of NRT is to replace nicotine while abstaining from tobacco. Varenicline is a partial nicotine agonist with some dopaminergic, which helps in decreasing craving and withdrawal symptoms.4 Bupropion is a relatively weak inhibitor of neuronal uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine.5

The effectiveness of all smoking cessation modalities were reviewed in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 267 studies involving 101,804 participants. Both NRT and bupropion were found to be superior to placebo in achieving prolonged abstinence of at least 6 months from the start of treatment. In a head-to-head comparison between NRT and bupropion, both showed equal efficacy. Different formulations of NRT performed similarly against each other however, combination NRT outperformed any single formulation. Compared to placebo, varenicline increased the odds of smoking cessation and was superior to both NRT and bupropion.6

In 2010, about 1.8% US adults reported using electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) which increased to 13% in 2013.7 Furthermore, their popularity is growing among minors and young adults, which may predispose them to nicotine addiction at an early age.8 E-cigarettes are devices that produce an aerosol by heating flavored liquid solvents containing nicotine. Inhalation of aerosol can lead to peak serum nicotine concentration within 5 minutes.9 Additionally, some of the commercially available e-cigarettes can allow users to adjust the strength of nicotine delivered which can vary from 5.4 mg/mL to 7.2 mg/mL. E-cigarettes are being advocated as a tobacco cessation tool based on harm reduction since it can provide rapid nicotine replacement. However, the evidence is sparse to support this theory. In one 12-month randomized controlled trial, 300 smokers with no intention to quit were randomized to either e-cigarettes that delivered nicotine or e-cigarettes that did not. No significant reduction in conventional tobacco cigarettes used was observed between the two groups.10 Furthermore, in the largest clinical trial to date, 657 smokers in New Zealand were randomly assigned to nicotine containing e-cigarettes, non-nicotine containing e-cigarettes, or nicotine patches to assess cessation rates. At 6 months, the cessation rate was not statistically significant between the cohorts.11 With minimal evidence of support for benefits and possible long term harm, the safety of e-cigarettes remains debatable. Additionally, an FDA analysis of cartridges revealed the presence of many carcinogenic nitrosamine, which further raised concerns for public safety.12

Besides pharmacologic therapies, behavioral therapy plays an important role in encouraging smoking cessation. Certain triggers may play a role in relapse for patients; identifying those triggers can allow early recognition and trigger control. Various forms of counseling are available to assist patients. Group counseling focuses on exercising self-control, developing coping skills and providing suggestions to prevent relapse; it has shown approximately 20% 1-year quit rate.13 Similarly, smoking cessation rates were higher at both 3 and 12 months with proactive telephone based counseling.14 Motivational interviewing is also observed to slightly increase quitting rate15 and may be beneficial in combination with first line pharmacotherapy.

The Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend screening each patient to identify tobacco use, as smoking leads to detrimental health issues. Patients attempting cessation without pharmacologic or behavioral therapy may be at increased risk for relapse. Although the use of e-cigarettes remains debatable, NRT, varenicline, and bupropion are first-line medications that reliably increase long-term smoking abstinence rates and can be even more effective when combined with counceling.16 As with any intervention, it is necessary to assess readiness of a patient to quit smoking, understand his or her belief regarding tobacco use, and assess available social support to prevent relapse.

Dr. Monil Shah is an internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by Scott Sherman, MD, Dept. of Population Health, NYU Langone Health

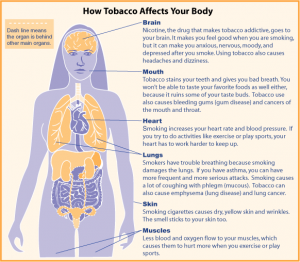

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

- World Health Organization. Tobacco. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en. Updated June 2016. Accessed February 15, 2016.

- Rigotti, N. A. Strategies to help a smoker who is struggling to quit. JAMA,308(15): 1573-1580.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Quitting smoking among adults–United States, 2001-2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=22071589. Published November 2011. Accessed February 15, 2016

- Varenicline: Drug information: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on February 12, 2016.)

- Bupropion: Drug information. UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on February 12, 2016.)

- Cahill, K., Stevens, S., Perera, R., & Lancaster, T. (2013). Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta‐analysis.The Cochrane Library. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23728690

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17: 1195-202.

- Dinakar C, O’Connor GT. The health effects of electronic cigarettes. The New England Journal of Medicine 2016; 375: 1372-81. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1502466

- Hajek P, Goniewicz ML, Phillips A,Myers Smith K, West O, McRobbie H. Nicotine intake from electronic cigarettes on initial use and after 4 weeks of regular use. Nicotine Tob Res 2015; 17: 175-9.

- Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, et al. Efficiency and Safety of an electronic cigarette (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS One 2013; 8(6): e66317. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0066317

- Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 382: 1629-37.

- Taupin D. Electronic Cigarettes: What We Know So Far. Clinical Correlations. http://www.clinicalcorrelations.org/?p=6396. Published August 2013

- Park, ER. Behavioral approaches to smoking cessation: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on February 12, 2016.)

- Borland R, Balmford J, Bishop N, et al. In-practice management versus quit line referral for enhancing smoking cessation in general practice: a cluster randomized trial. Family Practice. 2008;25(5):382-9.

- Lindson-hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015

- Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008 May.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/