Peer Reviewed

Learning Objectives:

1) When should diabetic myonecrosis be suspected?

2) What are the diagnostic criteria for diabetic myonecrosis? What is the pathophysiology?

3) What is the management of diabetic myonecrosis? How can it be prevented?

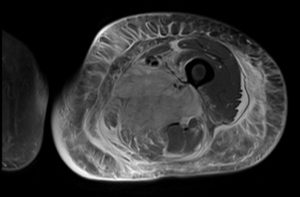

A 41-year-old female with a past medical history of poorly controlled type I diabetes (hemoglobin A1C [HbA1C], 13%), a right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) status post inferior vena cava filter placement in March 2017 presents with persistent weakness and left lower extremity pain for 2 months. Patient originally presented to an outside hospital for diabetic ketoacidosis. There she underwent drainage of a suspected infected hematoma found on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and was treated with doxycycline. Wound cultures grew no organisms. After discharge patient continued to have left lower extremity pain and weakness progressing to the point that she could no longer stand up on her own so she presented to our hospitals Emergency Department. On presentation, physical exam revealed a massively edematous thigh and labs were notable for hypoglycemia, an elevated creatine phosphokinase to the 200s and a normal white blood cell count. MRI showed an increase in size and confluence of a heterogeneously enhancing and edematous area involving the anterior and medial compartments of the left thigh and extensive subcutaneous and interfascial edema. These findings were felt to most likely represent diabetic myonecrosis. Throughout her hospitalization, the patient’s blood sugars were difficult to control. She remained in tremendous amounts of pain and eventually developed severe abdominal pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed asymmetric thickening and edema involving the soft tissue and musculature of the right anterolateral abdominal wall, which was thought to represent progression of the disease. The patient remained hospitalized for 4 months and was eventually discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Diabetic myonecrosis is a rare complication of long-standing (>15 years), poorly controlled diabetes. It is more common in type I diabetics and women.1,2 Patients usually present with unilateral lower extremity swelling and pain, most commonly in the thigh or calf, without preceding trauma.1 One important point to note is that our patient originally presented with myonecrosis of her thigh, which then progressed into her abdominal wall, an uncommon location, making this case an even rarer presentation of the disease. When patients present with swelling, this is often mistaken for DVT, cellulitis, abscess or hematoma. Patients normally do not present with any systemic symptoms and their inflammatory markers can be normal or elevated.2,3 Given the rarity of the disease and the similar presentation to other disorders, diabetic myonecrosis is likely under-diagnosed and misdiagnosed. One should have a high clinical suspicion for diabetic myonecrosis in patients who present with poorly controlled diabetes, unilateral leg swelling, a negative venous duplex, and no other systemic signs of infection. Diabetic myonecrosis is important to keep on the differential to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures or use of anticoagulation or antibiotics when not needed, as seen in the case above.

The first cases of diabetic myonecrosis were described in 1965 when 2 diabetics underwent muscle biopsy for clinical suspicion of tumors. Histologic examination showed diabetic microangiopathy and arteriosclerosis.4 Biopsy is the most definitive way to diagnose myonecrosis, with a specificity of about 95%. However, it is risky in poorly controlled diabetics as they have an increased risk of infection and a poor tendency to heal. Therefore the preferred diagnostic tool is an MRI, with a sensitivity of 90%.1,2 The most common imaging seen on MRI is enlargement of the involved muscle groups, loss of intermuscular septae on T1-weighted images and rim enhancing fluid collections in the intra and peri-muscular tissues secondary to edema or hemorrhage on T2-weighted images.2 MRI is sensitive for diabetic myonecrosis and should be used in place of muscle biopsy due to associated risks. Biopsy should only be used for the rarest presentations of myonecrosis with histologic findings including edematous connective tissue and fascia, pockets of edematous fluids deep to the fascia and pale, woody muscles with some reports showing a lymphocytic infiltration and patchy atrophic fibers.2

The pathogenesis of diabetic myonecrosis is not well understood and many theories have been put forth. The most widely accepted theory is that local arteriosclerosis causes an occlusion leading to an infarction, with local ischemia leading to edema causing a type of compartment syndrome.5 The hypoxia-reperfusion injury theory has also been proposed stating that a thrombolic or embolic event leads to ischemia and an inflammatory response and then the reperfusion leads to reactive oxygen species, worsening muscle damage and compartment syndrome due to edema.5 Other theories include vasculitis, hypercoagulable states, and phospholipid antibodies, but much more research needs to be done before a definitive etiology is established.

Medical management is preferred over surgical management in diabetic myonecrosis, given improved healing time and fewer complications.6 Therefore, treatment of choice for diabetic myonecrosis is tight glycemic control, NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, and rest in the acute phase. This is followed by gentle physical therapy when symptoms have resolved. There are reports of patients developing hemorrhage with too aggressive physical therapy early on.2 In the above case, when the patient began physical therapy it did appear that her symptoms worsened and physical therapy had to be scaled back until her symptoms started subsiding. There is no data on the best way to prevent diabetic myonecrosis, but the most reasonable approach would be tight glycemic control. The patient above had very poor glycemic control, coming in with an HbA1C of 13. She also had difficult to control glucose levels throughout her hospital course with ranges from the 50s to 500s, briefly requiring an insulin drip and then with subsequent worsening of her myonecrosis into her abdominal wall.

Diabetic myonecrosis is an under-diagnosed disease that presents in poorly controlled diabetics and can mimic other common disorders such as DVT or cellulitis. It is important to keep diabetic myonecrosis on the differential in order to prevent unnecessary use of antibiotics or invasive procedures. An MRI is a sensitive tool used to diagnose diabetic myonecrosis with muscle biopsy reserved for atypical cases. It is also important to note that tight glycemic control is one of the mainstays in treatment and likely prevents the disease, while other therapies include NSAIDs and rest with slow progression of physical therapy.

Dr. Allison Harrington is a resident physician at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by Valentina Rodriguez, MD, Endocrinology, NYU Langone Health

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

References:

- Trujillo-Santos AJ. Diabetic muscle infarction. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:211–15 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12502683

- Morcuende JA, Dobbs MB, Crawford H & Buckwalter JA. 2000. Diabetic muscle infarction. Iowa Orthopaedic Journal2065–74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10934627

- Mukherjee S, Aggarwal A, Rastogi A, et al. Spontaneous diabetic myonecrosis: report of four cases from a tertiary care institute. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2015;2015:150003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4482157/

- Angervall L, Stener B. Tumoriform focal muscular degeneration in two diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1965;1:39–42 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01338714

- Chester CS, Banker BQ. Focal infarction of muscle in diabetics. Diabetes Care. 1986;9(6):623–30 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3803154

- Kapur S, McKendry RJ. Treatment and outcomes in diabetic muscle infarction. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11(1):8–12