Peer Reviewed

Why does this matter?

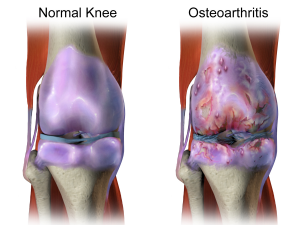

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability in the United States and is the most common type of arthritis. The pathogenesis involves the progressive destruction of articular cartilage in a joint, which is accompanied by new bone formation and synovial proliferation. On a cellular level, this process is believed to involve mononuclear cells and pro-inflammatory mediators that promote synovitis, as well as the up-regulation of aggrecanases and collagenases that promote cartilage catabolism [1]. Based on this proposed pathogenesis, the suppression of inflammatory mechanisms by intra-articular corticosteroids might theoretically reduce the progression of knee OA, with accompanying reduction in pain. This is an important area of study, as the pain associated with OA is the most prominent feature of the disease and is often undertreated.

What did we know before?

Though intra-articular corticosteroids have long been used to manage the symptoms of knee OA, there is an ongoing debate about their long-term efficacy and safety. A large Cochrane review from 2015 was unable to conclude whether there were clinically important benefits of intra-articular corticosteroids after 1 to 6 weeks, given the overall low quality of the evidence and heterogeneity between trials. Though some evidence suggests that the effect of intra-articular corticosteroids wanes after approximately 6 weeks, standard-of-care is to inject knees at a maximum frequency of every 3 months. An article published in Journal of the American Medical Association in 2017, “The Effect of Intra-articular Triamcinolone vs Saline on Knee Cartilage Volume and Pain in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” explored this topic.

How was the study designed?

McAlindon et al performed a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intra-articular administration of triamcinolone vs saline every 3 months over a 2-year period. Study participants were age 45 years or older, and met knee OA criteria as defined by the American College of Rheumatology. These criteria are based on a standardized questionnaire about knee pain, as well as tibiofemoral OA evident on radiographs. Eligibility criteria further included ultrasonographic evidence of effusion and synovitis. Participants were excluded if they had other disorders affecting the study joint, including systemic inflammatory joint disease, prior sepsis, or osteonecrosis; chronic or recent use of specific medications (eg, oral corticosteroids, doxycycline, indomethacin, glucosamine, chondroitin); recent intra-articular corticosteroid or hyaluronic acid; and any medical conditions that could be contraindications to participation (eg, poorly controlled diabetes, HIV, or hypertension). Study participants were asked to discontinue concomitant analgesics 2 days before each assessment to avoid masking pain and were advised to take acetaminophen only if needed.

The intervention in the study was the injection of 1 mL of triamcinolone 40 mg/mL; the control group received 1 mL of 0.9% normal saline. In both arms, synovial fluid (≤10 mL) was aspirated prior to the injection.

Participants attended 9 visits over a 24-month period, which were scheduled at 3-month intervals. Each visit included a knee exam and assessments of pain and stiffness. Participants were also subject to radiographs, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at standardized intervals. From the MRI, mean cartilage thickness, cartilage damage, and effusion volume were measured.

What were the study results?

The 2 primary outcomes of the study were change in knee cartilage volume and change in pain. Seventy participants were enrolled in each arm of the study. Intention-to-treat analyses were used for all outcomes. The group receiving triamcinolone injections was slightly older (59.1 years vs 57.2 years), but otherwise the 2 groups were matched in baseline characteristics including knee pain, function, and stiffness. Use of medication for breakthrough pain was 7%.

There was greater cartilage volume loss in the triamcinolone group than the saline group (-0.21 vs -0.10 mm cartilage thickness; between group difference -0.11 mm; 95% CI, -0.20 to -0.03; P < .01). There were no significant differences in the two groups in progression of cartilage denudation, bone marrow lesion, effusion volume, or trabecular morphology.

With regard to pain relief, the decrease in knee pain did not significantly differ across treatment groups: -1.2 units in the triamcinolone group vs -1.9 in the saline group (between-group mean difference, -0.64; 95% CI, -1.6 to 0.29, P < .17). There was also no significant difference in patient reported stiffness and function.

There were more adverse events in the saline group (n = 63 vs n = 52)— 8 were classified as treatment related: 3 in the saline group (cellulitis, injection site pain), and 5 in the triamcinolone group (facial flushing, injection site pain). There were no significant differences in serious adverse events.

What were the flaws of the study?

The study acknowledges several limitations. One of these has to do with the time points at which the measurements of cartilage and assessment of pain were conducted. These outcomes were ascertained every 3 months, and pain was not measured within the 4-week period after each injection, during which time benefits of steroid injections are greatest. Therefore, any transient benefit on pain could have been missed. In addition, participants were permitted to continue their usual medications, including analgesics, during the trial. Further, the study was targeted at osteoarthritic knees that had some degree of inflammation, determined using ultrasonography, a technique which may lack specificity. In addition, it is not entirely clear if the dose or frequency of the steroid injection was sufficient to generate a long term anti-inflammatory response. The study did not describe the majority of the adverse events.

What is the bottom line?

Triamcinolone injection did not slow cartilage volume loss yet accelerated the cartilage volume loss when compared to saline injection. Further, triamcinolone injection did not lead to a reduction in pain over saline injection 3 months after treatment.

Is this study a game changer?

Commentary By Dr. Michael Pillinger, MD, Chief of Rheumatology, VA New York Harbor Healthcare System

Dr. Lazarus reviews an important manuscript by McAlindon et al, in which repeated (every 3 months) intra-articular knee injections in patients with symptomatic knee OA resulted in no improvement in pain and increased cartilage loss compared to control injections with normal saline. The results of the study by McAlindon et al have generated discussion and some consternation among the rheumatology community and OA investigators in particular. Given a potential adverse outcome from intra-articular injections and no apparent symptomatic benefit, should one ever consider steroid injections? A negative answer to this question would cause a paradigm shift in how rheumatologists treat knee osteoarthritis, and would remove a key weapon from our already limited armamentarium.

However, while the study’s methodology is rigorous, the authors’ interpretations of their own results are somewhat flawed. For one thing, the authors’ finding that intra-articular steroid injections provided no pain benefit at 3 months was already so obvious as to be a truism. In usual practice, the intent of steroid injections in regards topain is generally to produce a transient benefit, typically lasting about 2—and certainly no more than 3—months, which may be critical for allowing some patients to continue with the activities of daily life. For many patients, such a benefit is routinely achieved. Thus, the potential pain benefit of steroids should properly be assessed not at the end of each treatment period, but as the area under the curve throughout the period, ideally assessed on a daily basis. Assessed in that manner, most rheumatologists would have little doubt of the beneficial outcome.

Given the undeniable pain benefit of intra-articular steroids in knee OA, the real concern is whether such injections have any long-term beneficial or adverse events. McAlindon et al frame their question as assessing a possible structural benefit of glucocorticoids on OA progression based on the assumption that OA is an inflammatory process but discover that OA patients receiving steroids have increased cartilage loss. This, indeed, is a matter of significant concern. However, does it imply genuine harm from steroids, and should we refrain from injections? To the former question, one must answer resoundingly, “maybe”. Importantly, the authors failed to assess the activity levels of their subjects. Is it possible that the loss of cartilage should actually have been ascribed, not to direct effects of the steroid, but to the fact that patients improved sufficiently in their pain to become more active, and so created more stress on their joints? This study cannot tell us, but the paradox may be that symptomatic improvement may permit clinical progression. In any event more research is needed.

[1] McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey WF, Price LL, et al. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA;317(19):1967-1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5283. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28510679

[2] Juni P, Harl R, Rutjes AW, Fischer R, et al. Intra-articular corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev;22(10). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005328.pub3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26490760

So—will I stop using intra-articular injections in practice? Absolutely not. I have no doubt that they provide symptomatic relief, and like many rheumatologists I use the intra-articular approach only when orals and topicals have failed to provide adequate benefit—thus usually minimizing exposure to patients who might otherwise have no recourse but to surgery. Moreover, the every-3-month regimen employed by McAlindon et al is not the only possible schedule, and some patients need less frequent injections. For example, many of us have patients who come seeking glucocorticoid injections only in the winter (when OA pain tends to be worse), or when they really need mobility (going on vacation, attending a family function). Data from the study by McAlindon et al provides no insight into how to manage these patients, who are presumably at lower risk. One important question implied by this study is whether we should prefer intra-articular hyaluronate to intra-articular steroid injections, since to date the former have not been shown to promote cartilage loss. However, hyaluronate injections are much more expensive (by a factor of hundreds), and the data for their pain efficacy is controversial. For the present, a decision between steroids and hyaluronate remains a matter of judgment.

Dr. Rebecca Lazarus is an internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by Michael Pillinger, MD, Chief of Rheumatology, VA NY Harbor Health Care System, Program Director, Rheumatology Fellowship Program, Professor, Department of Medicine NYU Langone Health

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons