By Monil Shah, MD and Arun Manmadhan, MD

By Monil Shah, MD and Arun Manmadhan, MD

Peer Reviewed

A 64-year old male with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and uncontrolled diabetes is brought to the emergency room with new onset substernal chest pressure radiating to his left arm. His electrocardiogram is notable for ST elevations in the anterior leads V2-V4. The patient undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention with deployment of a drug-eluting stent to his left anterior descending artery. His hospital course was otherwise unremarkable. The patient is initiated on an appropriate medication regimen. “What more,” the hospitalist ponders, “can I do to help improve this patient’s long-term outcomes?” The answer is cardiac rehabilitation.

Cardiac rehabilitation is a medically supervised program designed to help improve cardiovascular health [1]. The program promotes adoption of a healthy lifestyle by incorporating supervised exercise training, nutrition counseling, smoking cessation support, and management of other cardiac risk factors including blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes.

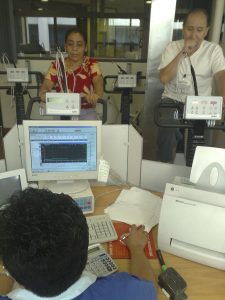

There are three phases to cardiac rehabilitation, each of which is designed to meet individual patient needs. The initial phase typically begins in the inpatient setting where the goal is to prevent negative effects of bedrest, maximize functional independence, provide counselling on lifestyle changes, and institute a post-discharge rehabilitation program. The second phase occurs primarily in the outpatient setting. Outpatient cardiac rehabilitation typically spans three months with frequent physician-monitored aerobic exercise sessions. A multidisciplinary team of physicians, nutritionists, physical/occupational therapists and mental health professionals provide individualized counselling on heart health and medical co-morbidities. The final phase of cardiac rehabilitation consists of a home-based exercise program and serves to reinforce beneficial lifestyle changes that were made in the prior phases [2]. Overall, cardiac rehabilitation is a dynamic, multifaceted therapeutic modality aimed at optimizing physical, mental and social functioning of patients with heart-related problems [2,3,4].

How effective are these intensive rehabilitation programs? A 2016 Cochrane systematic review set out to answer this question. This meta-analysis of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease analyzed 63 studies with a total of 14,486 participants [5]. Coronary heart disease was defined as any patient with prior myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), angina pectoris or coronary artery disease (CAD) based on angiography. With a median follow-up of 12 months, the study showed a significant reduction in pooled cardiovascular mortality (27 trials; RR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.64 to 0.86) and hospital re-admission (15 trials; RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70 to 0.96) in exercise based cardiac rehabilitation group when compared with control subjects [5]. While there was a significant mortality benefit, the quality of evidence for all outcomes in the study was evaluated as moderate due to a general lack of reporting of methods in the trials included. The population studied consisted of predominately low-risk, middle-aged males. Therefore, the results may not be applicable to all-comers with CAD. It is also important to note that median follow-up of 12 months as reported in the studies is limited in assessing for long term impact on mortality and morbidity. Additionally, lack of adherence was relatively high ranging from 21% to 48% in some trials with overall adherence of 80% or more achieved in only 71% of studies reported [5].

A benefit was also observed in patients with heart failure. A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials with 4740 participants who had reduced ejection fraction (<40%) and New York Heart Association Class II and III symptoms showed improved clinical cardiac outcomes with exercise interventions (either as a component of cardiac rehabilitation or independent training). At 12-month follow-up, there was a reduction in heart failure related hospital admission in the exercise group compared to the control group (15 trials, fixed-effect RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.92; p=0.005). The meta-analysis also showed a superior health-related quality of life in the exercise group when compared with controls (random-effect MD −5.8, 95% CI −9.2 to −2.4; p = 0.0007) [6]. Notably, there was no difference in polled all-cause mortality at one year. Trials in this meta-analysis were conducted in the era of contemporary medical therapy for heart failure, which suggests that cardiovascular rehabilitation has an additive benefit to optimal medical therapy.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death both in the United States and worldwide and is associated with significant morbidity [8]. Implementation of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease reduces cardiovascular mortality and hospital re-admission rates. It also improves exercise tolerance, anxiety, stress and depression which are highly prevalent in patients with coronary heart disease [9, 10, 11]. Due to this reason, cardiac rehabilitation is a class I indication for all patients with acute coronary syndrome, post-percutaneous coronary intervention, post-coronary artery bypass, chronic angina, and history of heart failure per the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association society guidelines [12].

Despite strong clinical recommendation, rates of referral to cardiac rehabilitation remain low within the United States. A recent study published by the National Cardiovascular Data Registry found that between 2007 and 2010, only 62% of the patients eligible for cardiac rehabilitation were referred at the time of discharge [13]. Various barriers to participation have been identified including financial constraints, patient’s illness perception, level of education, and lack of physician referral. Additionally, studies have also shown that females, older patients or patients with diabetes were less likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation [14,15,16]. Interestingly, in a study by Dunley et al., the strongest predictors of participation in cardiac rehabilitation were having a cardiologist as the primary provider (OR 18.82, P<0.001) and patients receiving an in-hospital referral (OR 12.16, P <0.001) [14].

In summary, cardiac rehabilitation improves both cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Despite strong evidence to support its utility, referral rates remain suboptimal. There are many barriers that prevent appropriate patients from being referred, and future quality improvement measures should be implemented to identify and overcome these barriers.

Dr. Monil Shah is an internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Health

Dr. Arun Manmadhan is a internal medicine resident at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by Richard Stein, MD, cardiology, NYU Langone Health

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References:

- Margolis, B., Dr. (2016, November). American Heart Association: What is Cardiac Rehabilitation? Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/CardiacRehab/What-is-Cardiac-Rehabilitation_UCM_307049_Article.jsp#.WXIZAIgrKM8

- De Macedo RM, Faria-Neto JR, Costantini CO, et al. Phase I of cardiac rehabilitation: A new challenge for evidence based physiotherapy. World Journal of Cardiology. 2011;3(7):248-255.

- Cardiac Rehabilitation: Putting More Patients on the Road to Recovery. (2017). American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Available at: https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/ahaecc-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_473083.pdf [Accessed 21 Jul. 2017].

- NYU Langone Health: Joan & Joel Smilow Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation Center. Retrieved from http://nyulangone.org/locations/joan-joel-smilow-cardiac-prevention-rehabilitation-center

- Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews2016, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001800. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub3

- Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2015;2(1): e000163. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000163.

- Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Liu Z, West R, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews2017, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD002902.

- World Health Organization: Cardiovascular Diseases. May 2017. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en.

- Carney, R. M., Rich, M. W., Tevelde, A., Saini, J., Clark, K., & Jaffe, A. S. (1987). Major depressive disorder in coronary artery disease. The American journal of cardiology, 60(16), 1273-1275.

- Schleifer, S. J., & Macari-Hinson, M. M. (1989). The nature and course of depression following myocardial infarction. Archives of internal medicine, 149(8), 1785-1789.

- Bush, D. E., Ziegelstein, R. C., Patel, U. V., Thombs, B. D., Ford, D. E., Fauerbach, J. A., & Feuerstein, C. J. (2005). Post‐Myocardial Infarction Depression: Summary.

- Smith, S. C., Benjamin, E. J., Bonow, R. O., Braun, L. T., Creager, M. A., Franklin, B. A., … & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. (2011). AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update. Circulation, CIR-0b013e318235eb4d. (AHA/ACC guideline – last paragraph)

- American College of Cardiology: NCDR Study Finds Low Referral Rates, Low Participation in Cardiac Rehab Among MI Patients. (2015, August).

- Dunlay, S.M., Witt, B.J.,Allison, T.G.,Hayes, S.N.,Weston, S.A., Koepsell, E., Roger, V.L. Barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation. American Heart Journal. 2009; 158(5): 852-859.

- Cooper, A., Lloyd, G., Weinman, J., & Jackson, G. (1999). Why patients do not attend cardiac rehabilitation: role of intentions and illness beliefs. Heart, 82(2), 234-236.

- Evenson, K. R., Rosamond, W. D., & Luepker, R. V. (1998). Predictors of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation utilization: the Minnesota heart survey registry. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 18(3), 192-198.