Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

By John Hwang MD, Cindy Fang MD, Neil Shapiro MD, Marty Fried MD || Illustration by Michael Shen MD || Audio Editing by Richard Chen ||

Time stamps

- Your collective differential [0:40]

- The test results (that you asked for) are in… [2:13]

- The hospital course, and the diagnosis (or is it?) [7:10]

- Validating a diagnosis: Base rate, adequacy, and coherence [8:30]

- Revisiting the differential [14:44]

- What to do when there is no final diagnosis? [17:39]

Subscribe to CORE IM on any podcast app! Follow us on Facebook @Core IM || Twitter @COREIMpodcast || Instagram @core.im.podcast. Please give any feedback at COREIMpodcast@gmail.com.

Show notes

- A working diagnosis should be subjected to a process of validation before the clinician accepts it as the final diagnosis in a case.

- Did you consider the base rate of the diagnosis (i.e how common or rare the disease actually is)?

- A proposed diagnosis is adequate when it can satisfactorily explain all or most of the patient’s key findings.

- A proposed diagnosis is coherent when all the aspects of the case (the patient’s features, clinical findings, illness course) conform to the expectations we have based on our understanding of that disease’s pathophysiology.

- Are there are other plausible diagnoses that are not sufficiently excluded?

- The rate of C. difficile colonization is low in healthy adults, but rises to 5-7% in elderly nursing home residents, and is reportedly as high as 25% in hospitalization inpatients according to some studies. The diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) therefore requires a compatible clinical syndrome, not just a positive toxin or PCR assay.

- Be aware of clinical scenarios that may deviate from the classic illness script for CDI. C. difficile presenting with ileus, CDI in a patient with an ostomy, CDI in elderly immunocompromised patients, and CDI presenting with systemic symptoms predating the onset of diarrhea (such as unexplained leukocytosis or delirium) are among the many permutations of this disease.

- Oral vancomycin is now the IDSA-recommended first line treatment for an initial episode of C. difficile colitis of any severity, as a growing body of evidence suggests metronidazole is inferior to vancomycin for this purpose.

- Cases without definitively-proven diagnoses are still valuable opportunities to learn and improve our practice.

- Always consider a second opinion, whether from a colleague, an expert, a collective intelligence, or a computer.

- Implement a system to actively follow-up on patient outcomes long after you’ve diagnosed and treated them. Passive feedback — relying on patients or other providers to bring you news of your hits and misses — is too infrequent and too skewed to be helpful.

- Diagnosis is ultimately a means to an end. Successfully managing a patient without having the benefit of an unquestionably-proven, all-encompassing final diagnosis is a skill characteristic of an expert clinician.

Transcript

JOHN

Hi everyone, John Hwang here. And welcome back to another episode of Hoofbeats, where we challenge you to solve diagnostically difficult, real-world cases alongside experienced clinicians. As always, I’m here with my partner, Cindy Fang.

CINDY

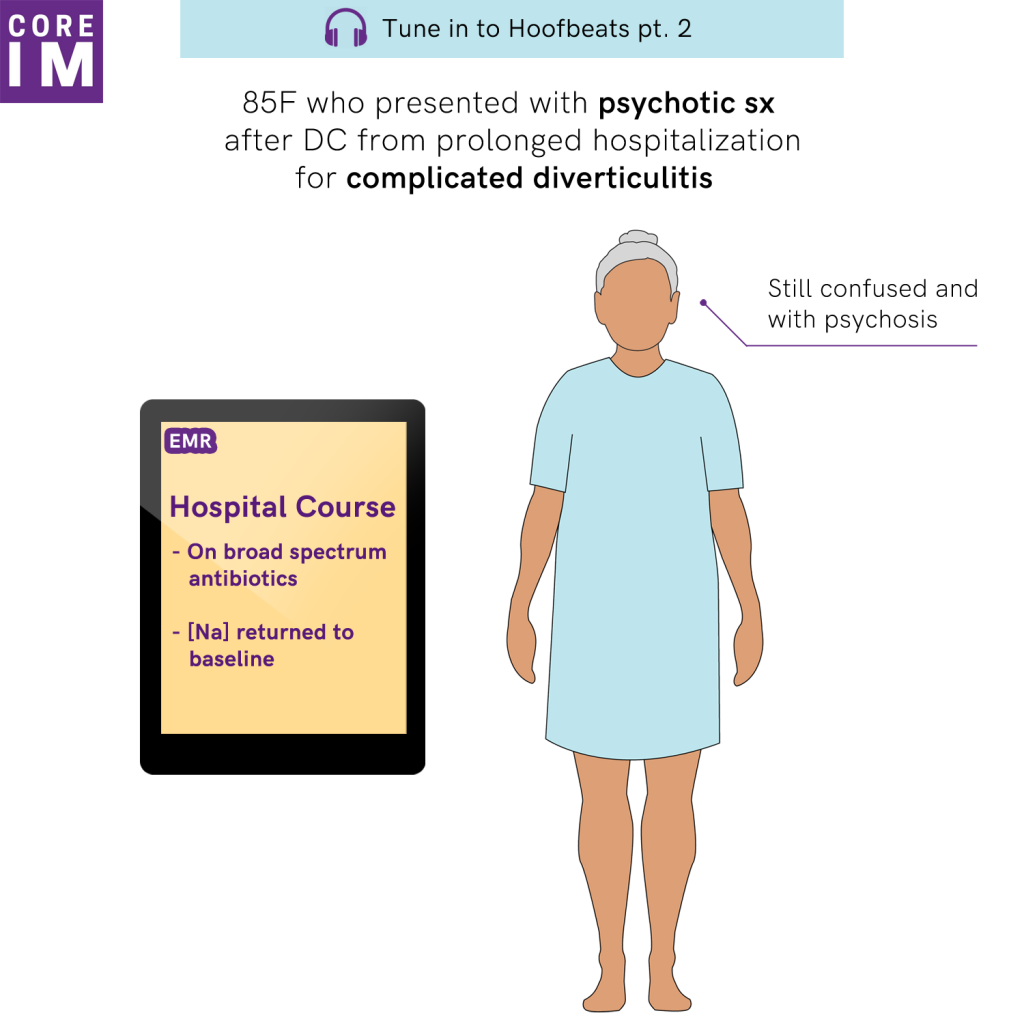

So two weeks ago we challenged you to solve the case of an 85 year-old woman brought in with psychotic symptoms just after being discharged from a prolonged hospitalization for complicated diverticulitis. And we asked you to not just solve the case, but to commit to your diagnoses by submitting them through the HumanDx platform.

JOHN

Honestly Cindy, I wasn’t too sure how this would play out. People are busy. So we were pleasantly surprised and really appreciative of the number and the quality of responses we got.

Collectively, you came up with no fewer than 39 distinct diagnoses to explain her findings.

Many of these were common, which we appreciate — this segment is called Hoofbeats, after all.

But some were new, at least to me — Cindy have you ever heard of “antibiomania”? Well, more than one person proposed it, and I can confirm after reading that it is a real term. Which I am going to be using a lot more if I can help it.

Mostly though, the diagnoses tended to fall into three broad categories: A CNS process, an infection, or an adverse effect of a medication given or withheld. Which if you remember is similar to our discussant.

There was less agreement about what to do next: You suggested 31 discrete tests or treatments. There was healthy debate: Some folks for example wrote to stop the steroids, others wrote to increase them; some wanted aggressive volume repletion, others wanted fluid restriction. One brave soul simply wrote, “Wait.”

JOHN

Well, Cindy, this was your patient, so I figured we could hear about the test results in the order our listeners wanted them?

CINDY

Fair.

JOHN

So, the number one test our listeners wanted: Head CT.

CINDY

It was normal. No acute intracranial abnormality.

JOHN

With contrast or without contrast? [Cindy: Without.] And it was done on the day of presentation? [Cindy: Yes.]

JOHN

Next test they wanted: Urinalysis.

CINDY

Completely normal.

JOHN

That surprises me. Just hospitalized, had a foley, surgery… clean UA? Pretty impressive. Urine culture?

CINDY

Clean.

JOHN

Blood cultures?

CINDY

Also clean.

JOHN

They wanted a chest X-ray.

CINDY

Areas of linear atelectasis, no acute intrapulmonary pathology.

JOHN

A surprising number of people wanted a TSH. I honestly wouldn’t have thought of this. Did you happen to get that?

CINDY

No, we did not.

JOHN

Urine chemistries. I think a lot of people were debating the significance of the serum sodium?

CINDY

None.

JOHN

I kind of assumed the hyponatremia was an epiphenomenon. Lumbar puncture?

CINDY

We didn’t get that either.

JOHN

You must’ve gotten the diagnosis before needing that. What about the brain MRI?

CINDY

Also not obtained.

JOHN

Huh. CT abdomen and pelvis?

CINDY

So it did show ileus and small bowel thickening slash enteritis, which was interpreted as postsurgical changes. No fluid or abscesses.

JOHN

The next test, C difficile PCR.

CINDY

That was actually positive.

JOHN

So Cindy, what happened in the patient’s hospital course? What was your diagnosis?

CINDY

After the head CT came back normal, infection dominated everyone’s thinking, though there wasn’t an obvious source. She was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics while awaiting culture results. The serum sodium return to her baseline of around 130 spontaneously. The CT chest showed PE like we said and she was also started on systemic anticoagulation but no one was convinced that was the primary etiology. After a day or two she wasn’t getting any better. Still confused, still psychotic.

When the C diff came back positive we added oral vancomycin. Within a day, her mental status began to improve, her white count declined. When other tests came back negative, especially all the cultures, broad spectrum antibiotics were stopped and she continued to recover. we began to suspect her presentation was in fact delirium from C difficile infection. Ultimately she made a full recovery, came back to her baseline status, and was discharged.

JOHN

And the sole treatment was the oral vancomycin. [Cindy: Mmhmm.]

JOHN

So delirium caused by C diff. How confident were you with that diagnosis?

CINDY

Hmmm… C difficile infection is a diagnosis that makes sense, in many ways, considering who she is. And yet, thinking about it carefully, there are definitely some problems with this theory.

JOHN

I think this is a useful opportunity to talk about the process of diagnostic validation. We all practice gathering histories from our patients, generating expensive differentials… now how do we make sure we’ve hit the right diagnosis?

CINDY

I agree. The stakes are big. Accepting an incorrect diagnosis doesn’t just hurt the patient, who gets mistakenly labeled and treated. It also hurts us, the learners, when we take away the wrong learning points, misfile our illness scripts in the wrong sections of our mental library.

JOHN

So before we accept the diagnosis, we need to take a moment to reflect on its strengths and weaknesses. This might take the form of a checklist. Checkbox one on that list? Ask yourself, did I consider the base rate of this diagnosis? In other words, am I proposing a common disease, or am I already going out on a limb by reaching for a zebra?

CINDY

Like we talked about in episode 1, a common way to get into trouble is to focus on how similar our patient is to our mental picture of a disease, without considering how common or rare that disease actually is. Most people who present to you in clinic complaining of headaches, sweating spells, and high blood pressure will not have pheochromocytoma.

JOHN

Right. In my experience, none of them have pheo. In this case Cindy I would argue we are invoking a pretty common diagnosis especially considering the population this patient comes from. Recently hospitalized, surgery, just finished with antibiotics. We’re not battling the odds here to start. Fair?

CINDY

Fair.

JOHN

Second checkbox, Cindy. Is our diagnosis adequate? In other words, can it explain all or most of the patient’s significant abnormal findings?

CINDY

In other words, if we accept momentarily that she has C difficile, is there anything left over that doesn’t fit?

JOHN

Exactly. Well put.

CINDY

Most findings in this case are nonspecific: Delirium, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, hyponatremia. C difficile could explain all of these, though so too could many other diagnoses. I admit I don’t think of C difficile as classically causing delirium, but literally anything in an elderly lady can. (seriously, there are pts I sneeze on or just look at the wrong way on rounds who would just turn delirious on me…) [John: …Yeah, don’t sneeze on your elderly patients…]

JOHN

Third checkbox. A closely related but distinct concept. The diagnosis must be coherent. Does the patient have most or all of the findings that would be expected if they in fact had the disease? And does everything make sense causally? For example, it’s worth noting that she failed to improve until she was started on C diff treatment, after which she quickly improved and ultimately made a full recovery. Her diagnosis and her hospital course in that sense are coherent; she behaves as we would expect if she truly had the disease.

CINDY

Now obviously correlation is not causation. Who’s to say she didn’t improve just because they removed her from the SNF? Maybe they were giving her completely the wrong dose of steroid and making her psychotic? Handoff errors, it’s not implausible.

JOHN

Right. (For all we know, maybe the radiator in her room at the SNF was emitting carbon monoxide.) But okay, in all seriousness, I’m willing to accept her clinical trajectory fits the diagnosis. Now what about this diagnosis isn’t coherent? (12:10 mins) So I’m going to challenge you Cindy. C difficile colitis is supposed to cause diarrhea. If she had C difficile, why wasn’t there report of diarrhea?

CINDY

I think that’s probably the biggest weakness in this theory. Somewhere between 3 to 26% of hospitalized adults are asymptomatic carriers of C difficile, depending on the study you look at. One study specifically reported a carriage rate of 5-7% in elderly adults coming from nursing facilities, like this patient. So this is the reason you have to be careful who you test. You generally do not want to test patients who are not having diarrhea.

JOHN

I assume though because this patient had an ostomy that she’s having semi-liquid stool all the time, right? How could you tell? Was she having an increase in ostomy output?

CINDY

We could see she was having a fair amount liquid output, yes. But it wasn’t liters and liters in the hospital. And we were not informed when she came in of any increase in ostomy output or change in stool consistency.

That being said, in a psychotic patient who’s refusing to answer your questions coming from a nursing home where to things like stool output aren’t really being charted, is it safe to assume when there’s no mention of diarrhea that there actually was not diarrhea?

JOHN

Right. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. At least when it comes to an unreliable historian with no collateral sources of information.

CINDY

Another possibility: the ileus on the CT was presumed to be post-op, but could it be a manifestation of C diff? It is a rare presentation of c diff, but I usually think of those patients usually present with bad fever, marked leukocytosis, severe abdominal pain ill appearing, on their way to developing toxic megacolon. They can initially present benign, but usually progress rapidly. I don’t know, our patient doesn’t appear sick enough to fit in that picture. There are rare case reports of c diff enteritis in post-colectomy patients, and some of them do present with ileus, but I can’t say we know enough about it. Still, it’s just not 100% unsatisfying.

JOHN

Yeah, I agree. Well, here’s another challenge. You said she got two antibiotics for her perforated diverticulitis, which I assumed were cipro and metronidazole. [Cindy: Cefpodoxime, actually.] How did she get C difficile if she was already on metronidazole? Metronidazole treats C diff.

CINDY

That’s true. There was also a short period of time after she finished her antibiotics before she came to the hospital. I also think it’s worth mentioning metronidazole has inferior cure rate compared to vancomycin.

JOHN

That’s true. It’s significantly worse than vancomycin. I think studies typically show a cure rate from 70 to 80%. This is one of the reasons that the IDSA no longer recommends it as first-line therapy for C difficile infection; as of earlier this year the guidelines have been updated.

CINDY

I also wonder if the fact she was on cefpodoxime at the same time is relevant. Quinolones, beta-lactams, and clindamycin are the antibiotics with the strongest association with C diff.

JOHN

Also a good point.

CINDY

Here’s a concern I had. If she had C diff, why didn’t the CT abdomen show pseudomembranous colitis?

JOHN

Well, from what you said, it seems the CT didn’t show pseudomembranes, or any of the classic CT hallmarks for C diff, like the accordion sign. But my understanding is that you often don’t see pseudomembranes. The most common findings are nonspecific ones seen in many forms of colitis, like wall thickening and pericolonic stranding.

CINDY

Fair. And who knows what effect her steroid use would have on the appearance of her colon on CT, if it’s driven by inflammation.

JOHN

Okay Cindy, we’ve talked about considering base rate, adequacy, and coherence of our working diagnosis, and based on our discussion so far, the diagnosis of C difficile isn’t perfectly coherent with what we know about the patient and her findings. And I think that just highlights the need for our last checkbox: Are there any other plausible diagnoses we haven’t sufficiently excluded?

CINDY

Well we can revisit the differential from our discussant and from our listeners. I think we have to acknowledge that a normal head CT doesn’t fully exclude some of the diagnoses in the CNS bucket, right? Cerebral venous thrombosis can be missed or be very subtle on a head CT; you really need an MRI or MR venogram if we want to fully evaluate that.

JOHN

That’s true. And I can think of several cases where an early stroke was missed because the initial head CT was read as negative.

CINDY

And then things like infectious or autoimmune encephalitis, vasculitis… You’d ideally have a lumbar puncture and an MRI or angiogram if you were suspicious enough.

JOHN

That being said, the fact that she improved without specific treatment for any of these entities is not very coherent I think with the hypothesis that she had an intracranial catastrophe, a primary neurologic event that caused this.

CINDY

Dr. Shapiro brought up the possibility of adrenal insufficiency because she’s chronically on steroids. We haven’t excluded that. The fact she isn’t hypotensive or hyperkalemic and doesn’t have a metabolic acidosis shouldn’t really reassure us, since we wouldn’t expect those things in tertiary adrenal insufficiency.

JOHN

Right. Were we at least able to confirm she was receiving her usual steroid dose at the outside facility? I can easily imagine something like that getting lost during handoff, and her not getting steroid. Actually I don’t have to imagine that, I’ve seen it.

CINDY

Yes, we confirmed that she was receiving her appropriate dose of steroid at the outside facility. Along the same lines, we also confirmed that she had not received any benzodiazepines, either during her hospitalization or after discharge when she was at the facility, so we thought that benzodiazepine intoxication or benzo withdrawal was unlikely.

JOHN

Keeping with the category of medications, metronidazole also has been known to cause encephalopathy and confusion since at least the 80s, another reason that it’s kind of falling out of favor I think. If you told me she had also been on cipro, I’d be even more concerned — the FDA has been warning about adverse neuropsychiatric effects of quinolones since 2016. That includes psychosis and mania, in addition to encephalopathy, seizures, movement disorders, and peripheral neuropathy.

CINDY

Time course is a little odd though, right? She got better while taking them in the hospital, was discharged, then got worse within two days of stopping the medicines.

JOHN

At least if we’re taking the history at face value. I agree, less coherent in that regard. Though difficult in general to disprove..

CINDY

Okay. So we’ve talked about some major things to think about when validating your working diagnosis. Base rate. Adequacy. Coherence. And competing theories. John, you weren’t involved in the case, so you can be dispassionate. What do you think about the diagnosis?

JOHN

OK. I have to be careful to be diplomatic here. So based on our discussion, we said C diff is common. It adequately explains her — admittedly nonspecific — presentation. Her illness appeared to respond to treatment as I would expect. But the diagnosis isn’t perfectly coherent in other ways — especially that I don’t see the large increase in ostomy output I’d expect. That really bothers me. That, along with the fact that plausible alternatives remain. So overall I personally think the diagnosis of C difficile is possible, even probable in this case. Certainly beyond the threshold to treat — I would definitely treat. But we haven’t proven it beyond reasonable doubt.

CINDY

You know what’s funny, though? Her chief complaint was, “they’re poisoning me with the pills.” So we’re saying she was kind of right all along.

JOHN

Ha. I’d quote William Osler, but it’s been overdone…

CINDY

So now what? What do we do with cases like this? Where the diagnosis is suspected, possible, probable… but not definite?

JOHN

Well, I think we’re relatively comfortable with the reality that we have to manage patients in spite of this kind of uncertainty, right? I mean, I see this all the time when I come in the morning, read resident H&Ps. We’re not too proud, in the right clinical context, to treat that wheezing, coughing patient with antibiotics, AND nebs, AND lasix, at least until we figure more out. [Cindy: Hey, they get better, right?]

But how do we learn from cases like this? Especially considering that the vast majority of patients we see in the hospital leave with “possible” or “suspected” diagnoses, not definite ones. We are missing out on a lot of potential learning if we simply write off these cases as “Who knows, really?”

CINDY

Well, to start, this is one reason we should keep a personal database of patients we’ve encountered. We’ll never know when we were wrong — or when we were right — if we never look to see what happened to our patients after their discharge or transfer.

JOHN

Right Cindy. Thought leaders in the field of clinical reasoning stress this point time and again. We can’t wait for the feedback to find us. Whether it’s the occasional update from your colleague in the clinic or the ICU, or the chance meeting with the patient on their next admission, passive follow up is too infrequent and too skewed to be helpful.

CINDY

Like those bumper stickers on the back of trucks? The ones that ask “I might be driving like I don’t give a flock, but how’s my driving? Call 1-877-12345.”

JOHN

Yeah. I always wondered what kind of feedback you’d get with that.

CINDY

Second… get a second opinion. It can help widen or focus our differential, and generates many useful clinical questions.

JOHN

I love being able to turn to the person next to me at work… I love listening to experts like Dr. Schapiro. Nothing will ever replace the benefits of consulting with a peer or a local expert. But consider the non-traditional sources of second opinions as well. We just crowdsourced a second opinion to a whole community of interested clinicians through HumanDx.

CINDY

And if you are a ‘misanthrope like me, maybe computer-assisted diagnosis is a better fit for you. VisualDx? Isabel?

JOHN

And third, maybe we should come to terms with our uncertainty. There’s this naive part of me, I think, that’s always just assumed — the primary purpose of a doctor is to make the diagnosis. I blame the media. Cultural depictions of doctors have them looking cool doing one of two things: Saving lives with some procedure like CPR or surgery, or saving lives by making some diagnostic coup, Dr. House-style.

CINDY

That’s not really the primary purpose of a doctor, though, right? The purpose of a doctor is to treat his or her patients.

JOHN

Right, exactly Cindy. When a patient comes in with symptoms — fever, cough, weakness — it could be anything. Our job is to constrain that uncertainty as much as possible, and then, more than anything, help our patients navigate through what’s left.

CINDY

It’s funny because I think as doctors we have a tendency to be allergic to uncertainty.

JOHN

Yeah. I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve read a discharge summary on one of my patients, and found that the intern wrote a nice story about the hospital course with a neatly presented and wrapped final diagnosis. When in fact you knew it was questionable? That ever happen to you?

CINDY

All the time. Diagnosis of “viral URI.” “Costochondritis chest pain.” “CHF exacerbation secondary to medication and dietary noncompliance.” It’s all the patient’s fault! But I know on rounds it’s not what we said.

JOHN

I’m trying to do a better job acknowledging my uncertainty openly, so they can feel empowered to put it in theirs. “Cause for her symptoms unclear at present.” You know the meteorologic models scientists construct to predict the weather? Or the Standard Model physicists created that predicted new particles? These models are imperfect, they’re approximations, yet they’re useful. I feel like a diagnosis in medicine is like that — a model that we construct, after observing the behavior of our system, our patient’s body, to predict the way that system will behave in the future. They’re a means to an end — And when our models fail, it’s an opportunity for us to learn.

As we were wrapping up the case Dr. Schapiro touched on this idea.

NEIL SHAPIRO

But I think as doctors, we try to come up with the final conclusion, right? And what the final word was on the case. And a lot of medicine is not satisfying in that way. But what’s really satisfying, right? Is Walking through all the possibilities here and, and thinking about all the possibilities and what’s my threshold to test not test. It was clearly different than your threshold to test and not test. Um, and that’s the difference in, you know, different practitioners. And it’s always interesting to talk about cases because I think that that gets you a level of comfort and being able to make your decisions.

NEIL SHAPIRO

I think when you’ve been proven, when you’ve been proven wrong a few times, you know, and then you know, your confidence I think goes in waves and it’s gone in waves my whole career. I’ve been really confident. I think I know everything. And then like the next week I’m like, oh my God, I, I don’t know what I’m doing right.

JOHN

Oh God. I thought that the waves would even out in the end, but good Lord [inaudible] the last four years, let me tell, you know…

NEIL SHAPIRO

I think, but I think that’s the beauty of it. And that’s, and that’s what makes it fun is that you’re, you’re never fully comfortable in your own shoes. But you do learn to enjoy it more and you learn to sort of enjoy the anxiety a little bit.

References

- Bott J, Ulrich RJ, Imlay H, Lopez K, Cinti S, Rao K. Clostridium difficile Enteritis in Patients Following Total Colectomy: A Genuine but Rare Clinical Entity. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2015;2(suppl_1). https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/2/suppl_1/1022/2635269

- Heneghan C, Glasziou P, Thompson M, et al. Diagnostic strategies used in primary care. Bmj 2009;338:b946. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19380414

- Kassirer JP, Gorry GA. Clinical problem solving: a behavioral analysis. Annals of internal medicine 1978;89:245-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/677593

- Kassirer JP, Wong JB, Kopelman RI. Learning clinical reasoning. Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

- McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2018;66:987-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29462280

- Rajkomar A, Dhaliwal G. Improving diagnostic reasoning to improve patient safety. The Permanente journal 2011;15:68-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3200103/

- Shattner, A. Teaching Clinical Medicine: The Key Principles. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 108, Issue 6, 1 June 2015, Pages 435–442, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcv022

- Tomé AM, Filipe A. Quinolones: review of psychiatric and neurological adverse reactions. Drug Saf 2011; 34:465–88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21585220

- Walker KJ , Gilliland SS, Vance-Bryan Ket al. Clostridium difficile colonization in residents of long-term care facilities: prevalence and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; 41:940–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8104968