Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

By Cindy Fang MD, John Hwang MD, Catherine Constable MD, Marty Fried MD || Illustration by Amy Ou MD || Audio Editing by Richard Chen

Time Stamps

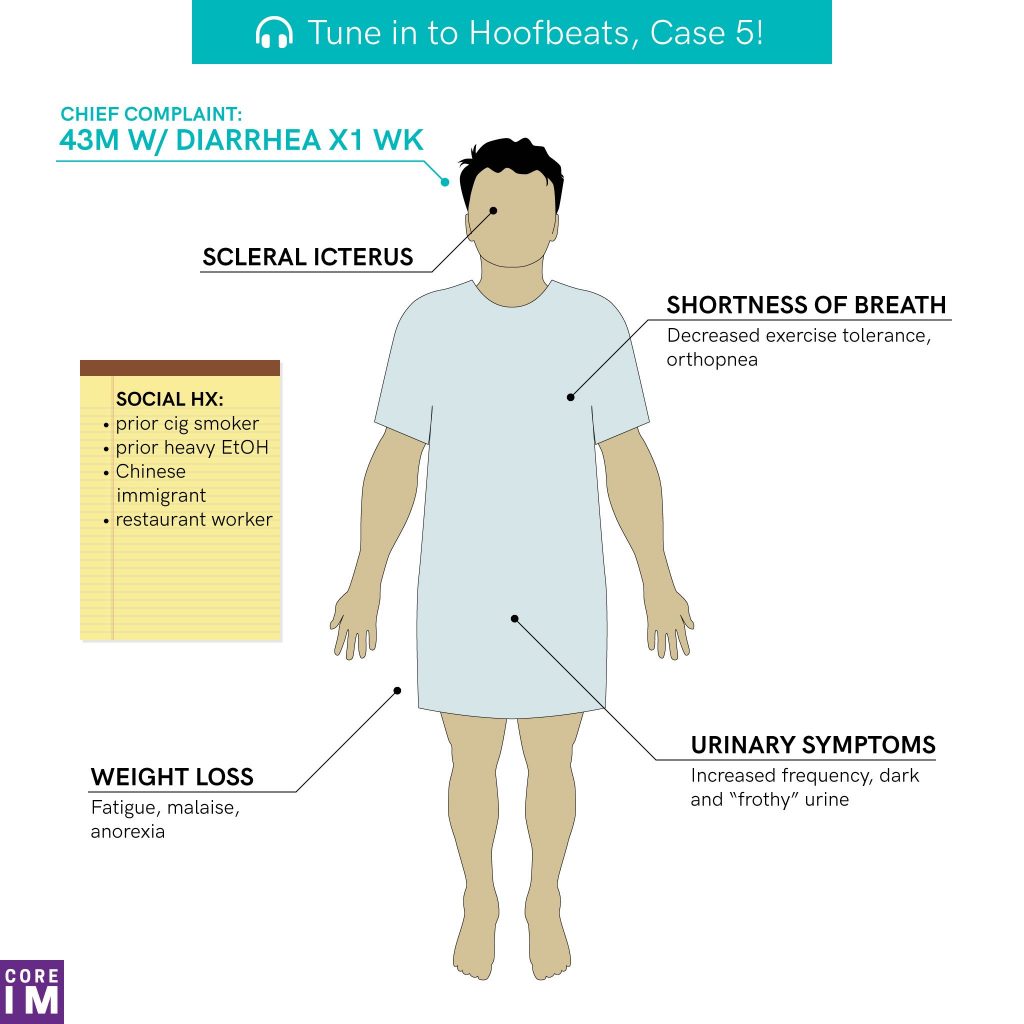

- Case [1:19]

- Diagnostic weight [8:42]

- Hypothesis driven reasoning [12:26]

- Anomalous clinical data [19:30]

- Final diagnosis [22:20]

- Take away points [31:21]

Human Dx Case link: https://www.humandx.org/o/co7yrer3dim2y59t5c0sbd370?s=FEED

Subscribe to CORE IM on any podcast app! Follow us on Facebook @Core IM || Twitter @COREIMpodcast || Instagram @core.im.podcast. Please give any feedback at COREIMpodcast@gmail.com.

Show Notes

- When building your illness scripts, pay attention to clinical findings that are characteristic for the diagnosis, rather than merely consistent with the diagnosis.

- Characteristic findings are hallmarks of a particular diagnosis. They are usually present, and when they are, they strongly support the diagnosis; when they are absent, they argue strongly against the diagnosis. I.e. their presence or absence significantly alters the likelihood of a diagnosis.

- Expert diagnosticians rapidly recognize characteristic findings, based on the clinical context.

- Hypothesis driven reasoning often involve both the fast and slow processor. Optimal utilization of the combination is crucial to avoid cognitive biases

- An anomalous clinical data is often times the only clue to the incoherence of a hypothesis. Its presence calls for rethinking your diagnosis creatively, don’t ignore it!

- Disease processes that involve multiple organ systems may have highly variable clinical presentation. Don’t be fooled by a rigid illness script.

References

- Cunha, Burke A. The Master Clinician’s Approach to Diagnostic Reasoning. The American Journal of Medicine , Volume 130 , Issue 1 , 5 – 7

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2011.

- Pelaccia, Thierry et al. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: the dual-process theory. Medical education online vol. 16 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5890. 14 Mar. 2011, doi:10.3402/meo.v16i0.5890 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21430797

- Szolovits, p & Pauker, S. Categorical and probabilistic reasoning in medical diagnosis. Artificial Intelligence. Vol 11, Issues 1-2, August 1978, Pages 115-144. doi.org/10.1016/0004-3702(78)90014-0 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0004370278900140

- Patel, V., Arocha, J., & Zhang, J. (2012-03-21). Medical Reasoning and Thinking. In (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. : Oxford University Press,. Retrieved 27 Nov. 2018, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734689.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199734689-e-37

- Shaked, Y et al. “Graves’ disease presenting as pyrexia of unknown origin” Postgraduate medical journal vol. 64,749 (1988): 209-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3050943

- Trivalle C, Doucet J, Chassagne P, et al. Differences in the signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism in older and younger patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1996;44:50-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8537590