Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

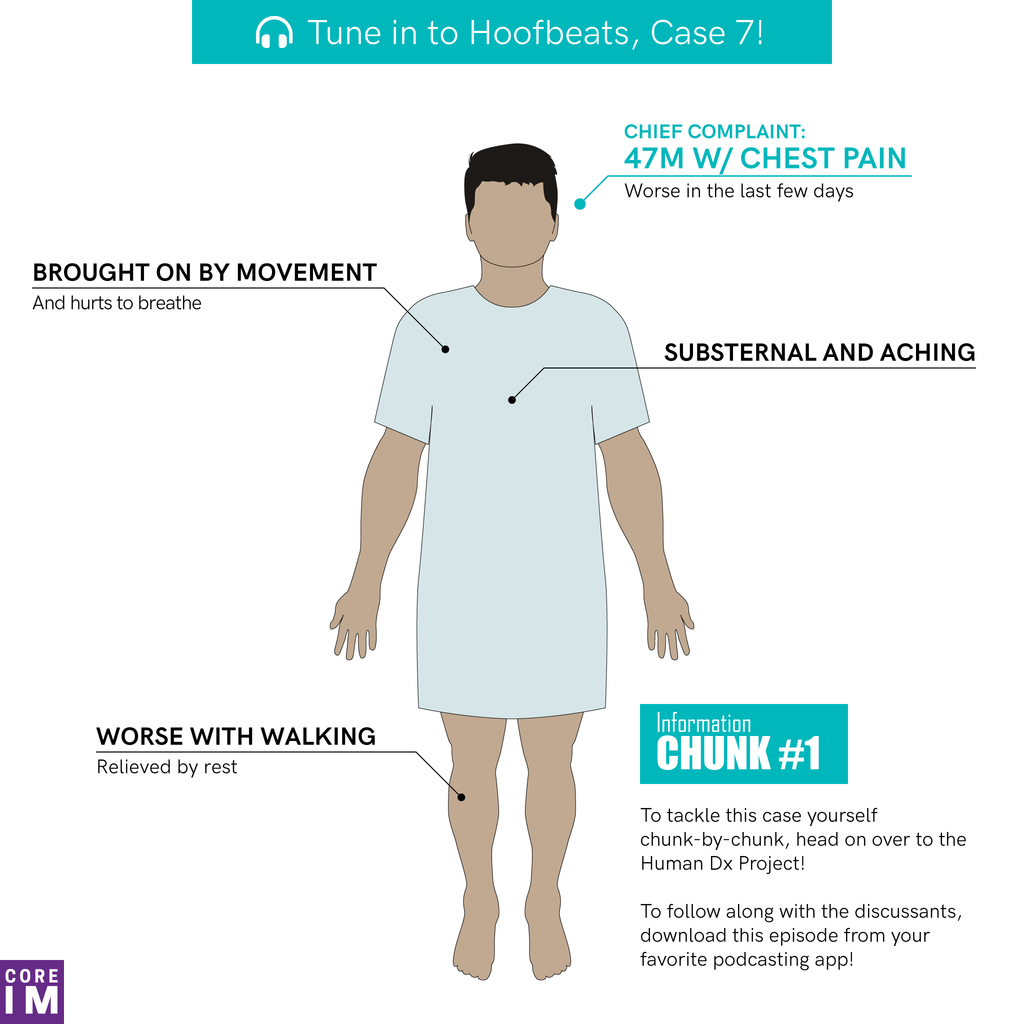

By John Hwang MD, Cindy Fang MD, Patrick Cocks MD, David Stern MD || Illustration by Amy Ou MD || Audio Editing by Harit Shah

Time Stamps

- New features in this episode [00:25]

- Data point 1: Early hypothesis generation? [03:20]

- Data point 2: Pertinent negatives? [11:18]

- Data point 3: Representativeness heuristic over-represented in medical education? [13:28]

- Data point 4: Economical hypothesis generation by expert clinicians [19:20]

- Data point 5: Diagnosing diagnostic error [22:10]

- Data point 6: Moving toward a final diagnosis [27:11]

- Case resolution [29:50]

HumanDx interactive case: https://www.humandx.org/o/16ilqkaxch8ezqzt113o45n58

Show Notes

- Expert clinicians tend to generate early diagnostic hypotheses in response to just a few initial cues about the patient and their illness (e.g. the chief complaint).

- To what extent this behavior in experts is involuntary or voluntary is debatable, and likely contextual. It is clear, though, that experts complement this early hypothesis activation with careful subsequent scrutiny, in the process of hypothesis evaluation/validation.

- It is important to differentiate between “no past medical history” and “no known past medical history.”

- Expert clinicians do not simply possess an expansive knowledge base, but also organize this knowledge in hierarchies that complement one another. In other words, the master diagnostician is not only an expert in diseases, but also in symptoms and syndromes, in pathophysiology, and in epidemiology and local patterns and prevalences of disease.

- Learning to recognize the most representative features of a particular disease is a necessary but by itself insufficient method of clinical learning.

- Spoiler alert! Gastrointestinal malignancies (gastric, pancreatic, colorectal) are among the cancers most strongly associated with venous thromboembolism.

- Trousseau’s syndrome refers to migratory superficial thrombophlebitis as a paraneoplastic manifestation of cancer. Coincidentally, Trousseau developed this syndrome himself and was later diagnosed with gastric cancer.

- Spoiler alert! Owing to a lack of data, there are no firm guidelines in the United States for routinely screening for gastric cancer in immigrants from high-prevalence regions (Latin America, Eastern Europe, and East Asia). As there is some data to support the effectiveness of universal routine gastric cancer screening in certain high-prevalence countries (Korea, Japan, Chile), it is not unreasonable to consider offering screening to first-generation immigrants in the US on a personalized, case-by-case basis.

References

- Cash BD, Banerjee S, Anderson MA, et al. Ethnic issues in endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2010;71:1108-12.

- Kassirer JP, Gorry GA. Clinical problem solving: a behavioral analysis. Annals of internal medicine 1978;89:245-55.

- Kassirer JP, Wong JB, Kopelman RI. Learning clinical reasoning. Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

- Mandin H, Harasym P, Eagle C, Watanabe M. Developing a “clinical presentation” curriculum at the University of Calgary. Academic Medicine 1995;70(3):186–93.

- Nendaz MR, Raetzo MA, Junod AF, Vu NV. Teaching Diagnostic Skills: Clinical Vignettes or Chief Complaints? Advances in health sciences education : theory and practice 2000;5:3-10.

- Noble S, Pasi J. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of cancer-associated thrombosis. British journal of cancer 2010;102 Suppl 1:S2-9.

- Saumoy M, Schneider Y, Shen N, Kahaleh M, Sharaiha RZ, Shah SC. Cost Effectiveness of Gastric Cancer Screening According to Race and Ethnicity. Gastroenterology 2018;155:648-60.