Peer Reviewed

Let’s start with a case. Mr. B is a 67-year-old male with a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. As his primary care physician, you wish to add empagliflozin and dulaglutide to his medication regimen, which consists of metformin, lisinopril, aspirin, gabapentin, and atorvastatin. Mr. B is a Medicare beneficiary and is enrolled in a Part D prescription drug plan. His most recent Medicare explanation of benefits (EOB) summary has informed him that he is nearing the “coverage gap.” He asks you what this means, and how much these new prescriptions will cost.

This request would make many providers uncomfortable. We are accustomed to feeling adequately prepared to answer our patients’ medical questions; we are often not equipped to discuss the costs of the care we provide. The complexity and prevalence of Medicare Part D plans, coupled with recent changes to their structure, warrant a review of the key features of this program that all physicians should feel comfortable discussing with patients.

Before diving into the specifics, let’s review some Medicare basics. The program was established in 1965 for all patients aged 65 and older, as well as other protected groups, such as those with end-stage kidney disease. There are currently 61 million Americans enrolled. Individuals apply separately to three main Parts: A, B & D. Part A covers inpatient hospital stays, skilled nursing facilities, and hospice care, Part B covers physician’s visits and outpatient services, and Part D covers outpatient prescription medications.1 There is a Part C (also known as Medicare Advantage) but this is not a separate benefit; it is a single plan offered through private companies that combines benefits from Part A, B, and typically D.

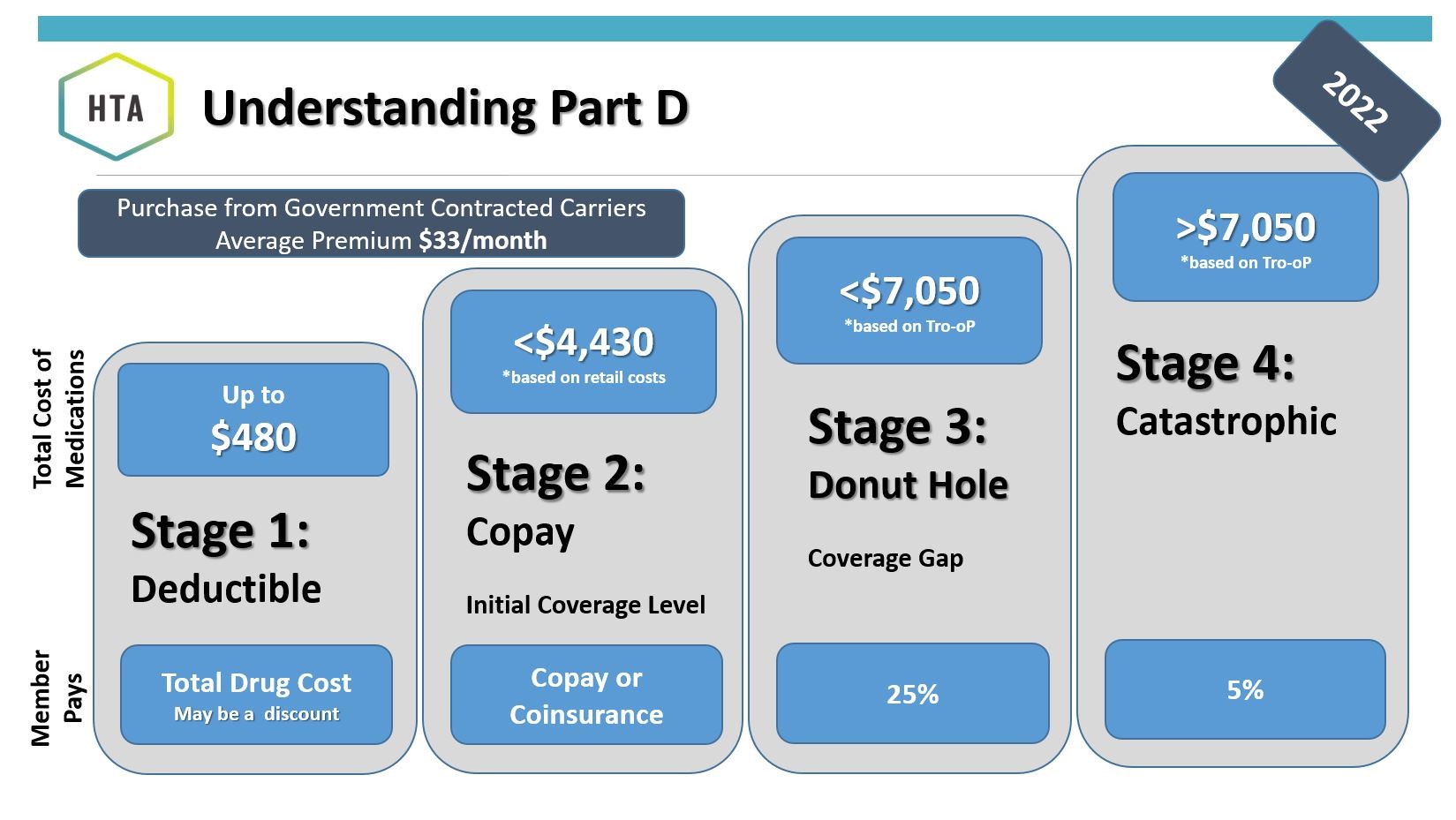

The Medicare Part D benefit was established in 2003 as part of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) and went into effect in 2006. Enrollment in Part D is voluntary, and as of 2021, 48 million Americans (79% of beneficiaries) were enrolled.2 Coverage is provided by private insurers that contract with the federal government. In each state, there are dozens of plans for beneficiaries to choose from that vary in their cost structures, formularies, and benefits.3 All Part D plans have the same basic phases of coverage: the deductible phase, the initial coverage phase, the coverage gap phase, and the catastrophic coverage phase (see Figure). Depending on what phase of coverage the patient is in, the amount of money they pay for their prescribed medications varies. On January 1st of the following year, the patient returns again to the deductible phase.

Until they have reached their deductible, the patient is responsible to pay 100% of drug costs out of pocket on top of the monthly premium. Deductibles vary across plans, but can be no higher than $480 in 2022.2 The average monthly Medicare Part D premium in 2022 is $33, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).4

During the initial coverage phase, the private insurer covers the majority of the medication cost, while the patient contributes a fixed amount through either co-insurance or a co-payment. The amount the patient pays is medication-dependent. The initial coverage period ends after $4430 of total medication costs have accumulated.2 Total medication costs exclude amounts paid through monthly premiums but include amounts paid through deductible, co-pays, or co-insurance.

In the coverage-gap phase (between $4430 and $7050), the patient is responsible for 25% of the cost of both generic and brand-name medications. For brand-name medications, the drug manufacturer provides a 70% discount, while the private insurer covers the remaining 5% of the cost. For generic medications, the private insurer covers the full remaining 75%.

In the past, the coverage gap was indeed a gap. You may have heard it referred to as the “donut hole”. Once an enrollee’s total drug spending exceeded the initial coverage limit, they were required to cover 100% of drug costs until their spending reached the threshold amount qualifying them for “catastrophic coverage.” Many analyses showed that beneficiaries reduced their medication use when they reached this coverage gap.5 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) sought to address the donut hole and included provisions to reduce the percentage paid by enrollees by 2020. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 accelerated this process.6 The current structure, in which the enrollee’s expenditure is set at 25% of drug costs during the coverage gap phase, has led some to say that the donut hole has been closed.7

When speaking with patients, it’s important to be mindful that even with the donut hole closed (from 100% to 25% of costs), the amount they pay for medications can still increase as they transition from the initial coverage phase to the coverage gap phase. For example, if the patient paid a $50 co-pay for a $600 medication in the initial coverage phase, they will now pay $150 (25% of $600) in the coverage gap phase.

In all Part D plans, the “catastrophic coverage” threshold is reached once the patient has contributed $7050 out of pocket for their medications.2 Nearly 1.5 million enrollees reached this stage in 2019.8 After reaching the catastrophic coverage threshold, patients are responsible for 5% of the total drug costs or $3.95 per generic and $9.85 per brand-name drug, whichever is greater. For expensive drugs such as novel chemotherapeutic agents, this 5% co-insurance can be significant, and there is currently no hard cap on out-of-pocket spending. The remainder of the medication costs over the catastrophic threshold is covered by the private insurer and Medicare. Interestingly, the private insurer is only responsible for 15% of the drug costs over the catastrophic threshold, while Medicare (fueled by taxpayer money) covers the remaining 80%.2

Equipped with this information, we can return to Mr. B and describe the coverage gap and inform him that the amount he pays for some of his medications may increase in this phase of his coverage. It will be difficult to quantify the extent of this increase, as it will vary according to which plan Mr. B has selected. During a regular clinic visit when there are an abundance of health concerns to address, reviewing the patient’s individual policy in detail is likely not reasonable. As providers, we will never be equipped to answer all of our patients’ questions about coverage and costs; the reality is that the US healthcare system is far too fragmented and complicated. But by understanding the basic framework, we can engage in informed conversations with our patients about the very practical implications of the medication regimens we design.

Figure

2022 Medicare Part D Prescription Coverage Phases

Tro-oP=True out of pocket costs

From: HTA Insurance Services. Prescription drug plans in Medicare. HTA Financial website. Published 1 February 2022. Accessed 4 April 2022. https://htafinancial.com/individuals/medicare-part-d/ – 1613746245069-10dea5cb-fd49

By Michael Papazian is a 1st year medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Dr. Adam Schwartz, internal medicine, NYU Langone Health

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons – source: Prescription medicine.svg, http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en

References

- Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of Medicare. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicare/ Published 13 February 2019. Accessed 9 October 2021.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-the-medicare-part-d-prescription-drug-benefit/ Published 13 October 2021. Accessed 4 April 4 2022.

- Cubanski J, Neuman T, Damico A. Closing the Medicare Part D coverage gap: Trends, recent changes, and what’s ahead. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/closing-the-medicare-part-d-coverage-gap-trends-recent-changes-and-whats-ahead/ Published 21 August 2018. Accessed 9 October 2021.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS releases 2022 projected Medicare Part D average premium. CMS website.

https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/news-alert/cms-releases-2022-projected-medicare-part-d-average-premium Published 29 July 2021. Accessed 14 August 2022. - Park YJ, Martin EG. Medicare Part D’s effects on drug utilization and out-of-pocket costs: A systematic review. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(5):1685-1728. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12534

- Span P. Medicare’s Part D doughnut hole has closed! Mostly. Sorta. New York Times website. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/health/medicare-drug-costs.html?searchResultPosition=4 Published 17 Jan 2020. Accessed 9 October 2021.

- Unuigbe A. The Medicare Part D coverage gap, prescription use, and expenditures. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):442-450. doi:10.1177/1077558718806437

- Cubanski J, Neuman T, Damico A. Millions of Medicare Part D enrollees have had out-of-pocket drug spending above the catastrophic threshold over time. Kaiser Family Foundation website.. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/millions-of-medicare-part-d-enrollees-have-had-out-of-pocket-drug-spending-above-the-catastrophic-threshold-over-time/ Published 23 July 2021. Accessed 9 October 2021