Faculty Peer Reviewed

The patient is a 29 year old overweight male presenting to clinic with complaints of reflux symptoms. He says that spicy foods aggravate these symptoms. In addition to weight loss counseling, he is given a prescription for esomeprazole along with a patient handout containing recommendations on foods to avoid and other behavior modifications that may ameliorate his symptoms.

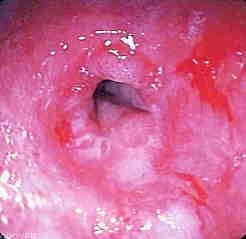

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus at least once a week, causing troublesome symptoms such as heartburn (the sensation of substernal burning) or complications.1 These potential complications include Barrett’s esophagus, adenocarcinoma, laryngitis, pharyngitis, aspiration pneumonia, chronic sinusitis, and dental decay. GERD is very common in the Western world with an estimated prevalence of 10-20%, versus <5% in Asia.2

While GERD is a multifactorial disease involving anatomical and functional factors, the main pathogenetic mechanism is considered to be transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR).3 An increased frequency of TLESR episodes, with or without impaired lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone, and/or gastric or esophageal motor dysfunction, may lead to GERD. Studies of twins suggest that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in predisposing an individual to developing GERD.4 Among the environmental factors, being overweight, certain dietary habits, lack of physical activity, and cigarette smoking have all been implicated as risk factors. However, the pathogenetic role of these factors and the utility of behavioral modification are issues that are still under debate.

Among lifestyle factors, diet has long been implicated in the induction and exacerbation of GERD symptoms. It has thus become common practice for physicians to advise patients to avoid certain foods. However, conflicting results exist in the literature regarding which foods are “refluxogenic.â€3 This apparent incongruity raises some important questions: Is dietary modification an evidence-based approach to treating patients with GERD, and if not, why is it used as one of the first-line treatments? To address these issues, a review of the literature on the role of diet in GERD was conducted with a focus on evaluating the validity of published results.

Based on clinical observations that fat seems to elicit heartburn, patients are generally advised to avoid fatty meals.5 Some studies have shown that fat reduces LES pressure; however, other studies show no significant difference in LES pressure or the amount of regurgitated acid. In a study by Ruhl et al, 12,349 subjects were followed over 18.5 years. Upper endoscopy and symptom interviews were used to assess reflux symptoms in relation to dietary fat intake. Results showed higher reflux disease hospitalization rates in subjects with higher body mass index, but no association between higher fat intake and reflux-disease hospitalization rates.6 However, in another study by Shapiro et al, a group of 50 patients with GERD underwent 24-hour pH monitoring along with a dietary intake record and a GERD symptoms checklist; patients who consumed more cholesterol and saturated fats were significantly more likely to experience a perceived reflux event.7

Alcohol and coffee are two other items commonly thought to exacerbate GERD symptoms. In a study involving public health surveys in Norway (N >40,000), Nilsson et al did not find that alcohol or coffee were risk factors for reflux symptoms.8 Furthermore, in the previously mentioned study by Shapiro, alcohol consumption was associated with fewer sensed reflux events. Similarly, while early observational studies have cited coffee as a trigger for reflux-related symptoms, two large epidemiological studies have shown no relationship between coffee drinking and GERD.3 Additionally, in a randomized controlled study, Boekema et al found that ingestion of coffee had no effect on postprandial reflux time, number of reflux episodes, or LES pressure.9 These findings were true for both healthy subjects and patients with GERD. Interestingly, in a population-based nested case-control study involving 211 subjects, coffee consumption was found to be less in those with reflux symptoms. However this association may reflect avoidance of coffee because it aggravated GERD symptoms.10

Other commonly implicated foods include chocolate, mint, citrus, and spicy foods. In a recent review article, Kaltenbach et al evaluated 100 studies concerning GERD and lifestyle modification and found no evidence supporting an improvement in GERD measures following dietary interventions.11 Although patients frequently cited the above-mentioned foods as inciting agents for reflux episodes, little data regarding actual physiologic effects and very few studies addressing the effects of cessation of these foods on GERD symptoms were found.

To summarize, the deep-seated belief that certain foods trigger GERD-related symptoms seems to be based on dated studies with significant flaws. Recent, larger studies show conflicting evidence regarding the relationship between specific foods and GERD. Additionally, there is a dearth of randomized controlled trials regarding the efficacy of dietary modification, and many studies are based on self-report of dietary intake and are thus subject to recall bias. Physicians should realize that dietary modification alone may help patients with mild GERD but is unlikely to control symptoms in patients with more severe disease. If dietary modifications are to be used as part of a treatment plan, recommendations should be made based on patient-specific susceptibilities rather than on generalizations founded on insubstantial evidence.

Dr. Srinivasan is a recent Graduate of NYU School of Medicine,  Class of 2010

Peer review by Dr. Gerald Villanueva, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology

References:

1. Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900-1920.

2. Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54(5):710-[GV1] 717.

3. Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, et al. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(14):1690-1701.

4. Mohammed I, Cherkas LF, Riley SA, Spector TD, Trudgill NJ. Genetic influences in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a twin study. Gut. 2003;52(8):1085-1089.

5. Meining A, Classen M. The role of diet and lifestyle measures in the pathogenesis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(10):2692-2697.

6. Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Overweight, but not high dietary fat intake, increases the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease hospitalization: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study. First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(7):424-435.

7.  Shapiro M, Green C, Bautista JM, et al. Assessment of dietary nutrients that influence perception of intra-oesophageal acid reflux events in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006[GV2] ;25(1):93-101.

8. Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53(12):1730-1735.

9. Boekema PJ, Samsom M, Smout AJ. Effect of coffee on gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with reflux disease and healthy controls. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(11):1271-1276.

10. Nandurkar S, Locke III GR, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Cameron AJ, Talley NJ. Relationship between body mass index, diet, exercise, and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in a community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(5):497-505.

11. Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):965-971.

12. DeVault KR, Castell DO; American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):190-200.

[GV1]Should be 717

[GV2]The article was in 2007