Peer Reviewed

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EA) is a rapidly growing risk to public health in the US, with nearly 17,000 new diagnoses and 16,000 EA deaths in 2017.1 Although treatment options have improved for patients whose disease is caught early, 40% of EA is still diagnosed in advanced stages, conferring a terrible prognosis.2 The overall five-year survival rate is consequently among the worst for any cancer. Methods to detect and intervene earlier in the progression of this disease should have a large impact on the health of a growing number of patients.

The only known precursor lesion for EA is Barrett’s esophagus (BE), a condition in which intestinal columnar epithelium replaces the normal squamous epithelium of the distal esophagus.3 BE risk is greatly increased in patients with chronic gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), leading to a proposed progression from reflux-induced inflammation to BE, which then progresses to low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and eventually EA.4 Since BE can be identified fairly reliably with endoscopy and biopsy,2 this progression makes EA an ideal theoretical candidate for screening.5Â

Looking at official society recommendations, you might draw the conclusion that BE screening with endoscopy is supported with robust evidence. The American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy all recommend screening endoscopy in patients with significant BE risk factors (typically older white men with chronic GERD) and routine surveillance endoscopy after BE diagnosis.6,7 Accordingly, the practice of using endoscopy to screen for and surveil BE is widespread.8 And yet the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which is charged with developing recommendations for preventive medicine, has never endorsed screening endoscopies. This is probably because, despite the professional society recommendations, good evidence for BE screening does not exist.

The first issue in using endoscopy to screen for BE comes with identifying whom exactly to screen. Many patients with BE have no preceding history of GERD symptoms, and in turn EA patients often do not have a previous diagnosis of BE. A meta-analysis of 20 observational studies showed that nearly half of patients with diagnosed short-segment BE had no preceding symptoms.9 Â Similarly, a retrospective study of more than 100 patients with EA showed that roughly 40% had not experienced any symptoms.10 Clearly, any attempt to screen based on the presence of risk factors is going to miss a large number of cases. Accordingly, fewer than 10% of patients with EA diagnoses have a prior BE diagnosis, indicating that current screening approaches are falling short.11 One potential work-around is to expand screening to any patient with GERD or any other risk factor, but this would create an enormous screening pool that would likely make screening not cost-effective. There is currently no evidence from randomized controlled trials to support any particular inclusion criterion for identifying BE or reducing EA deaths, further complicating the issue

An equally difficult question arises after the diagnosis of BE: should the patient get surveillance endoscopies to monitor for the development of dysplasia or cancer? Intuitively, it would make sense to surveil these patients. If you know where a cancer is likely to develop, you should be able to catch it earlier and improve the patient’s prognosis. Indeed, several prospective and retrospective cohort studies have shown a significant reduction in risk of death from EA in BE patients who undergo surveillance endoscopy compared to those who do not.12 None of these studies, however, accounted for a potential false elevation in survival numbers due to diagnosis earlier in the disease course (“lead-time biasâ€). In the single cohort study that adjusted for this potential bias, the beneficial effect of surveillance was not seen.13,14 Despite the unclear mortality benefit, surveillance was related to lower stage cancer diagnosis in all of these studies. Again, this question is plagued by the lack of data from high quality randomized controlled trials. Luckily, a large, decade-long RCT of over 3,000 patients is currently underway in the United Kingdom to address the impact of surveillance after a diagnosis of BE.15

Esophageal adenocarcinoma offers a valuable lesson in the difficulty of making population-level screening recommendations in the absence of a strong evidence base. The disease, which has a poor prognosis, is preceded by a well-described pre-cancerous lesion with well-known risk factors. All of this should make it an ideal target for screening. And yet there are currently not enough data for the USPSTF to make even a cautious or partial recommendation. Until there is strong evidence from well-designed trials, providers and patients are left to carry out uncertain policy with unknown consequences.

Dr. David Collins is a 4th year medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Reviewed by Michael Tanner, MD, associate editor, Clinical Correlations

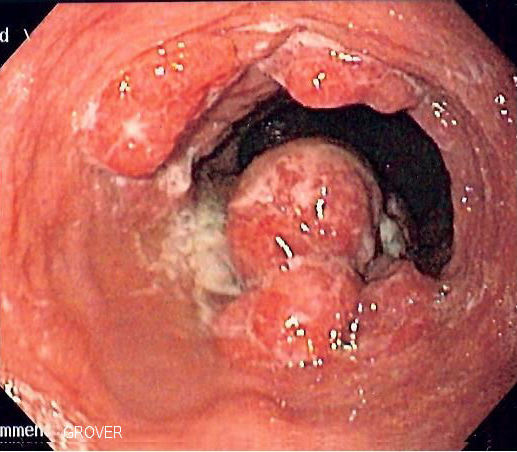

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Esophageal_adenoca.jpg (2 June 2006, Samir)

References

- Thrift AP. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: how common are they really? Dig Dis Sci.  2018;63(8):1988-1996.

- Wani S, Rubenstein JH, Vieth M, Bergman J. Diagnosis and management of low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: expert review from the Clinical Practice Updates Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(5): 822-835.

- Spechler SJ. Clinical practice. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):836-842.

- Haggitt RC. Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1994; 25(10):982-993.

- Wilson JMG, Jungner G, and World Health Organization; 1968. Principles and practice of screening for disease. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650 Accessed November 19, 2020.

- American Gastroenterological Association, Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):1084-1091.

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(1):30-50.

- ASGE Stsndards of Practice Committee, Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.

- Amadi C, Gatenby P. Barrett’s oesophagus: Current controversies. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(28):5051-5067.

- Taylor JB, Rubenstein JH. Meta-analyses of the effect of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux on the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1730-1737.

- Chak A, Faulx A, Eng C, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or cardia. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2160-2166.

- Bhat SK, McManus DT, Coleman HG, et al. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma and prior diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based study. Gut. 2015;64(1):20-25.

- Codipilly DC, Chandar AK, Singh S, et al. The effect of endoscopic surveillance in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(8):2068-2086.

- El-Serag HB, Naik AD, Duan Z, et al. Surveillance endoscopy is associated with improved outcomes of oesophageal adenocarcinoma detected in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2016;65(8):1252-1260.

- Old O, Moayyedi P, Love S, et al. Barrett’s Oesophagus Surveillance versus endoscopy at need Study (BOSS): protocol and analysis plan for a multicentre randomized controlled trial. J Med Screen. 2015;22(3):158-164.