Commentary by Rosemary Adamson, PGY2, Â Deena Altman PGY-1 and Harold Horowitz, Professor of Medicine, Section of Infectious DiseasesÂ

Commentary by Rosemary Adamson, PGY2, Â Deena Altman PGY-1 and Harold Horowitz, Professor of Medicine, Section of Infectious DiseasesÂ

Syphilis is back! You know the drill: an 80-something year old man presents with dementia and you send the TSH, B12 and RPR and get a head CT, all the while expecting some microvascular disease & age-related cortical volume loss. Imagine my surprise when my VA patient had a positive RPR and then the lumbar puncture returned a positive VDRL. To be fair, he wasn’t married and was living with his third common-law wife, but I still find it hard to think of elderly people as having sexually-transmitted diseases! But we must think of all our patients as at least potentially having STDs and do our best to ask all the embarrassing questions of the sexual history and then screen appropriately – because syphilis is on the rise!

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene recently released a report on the striking increase in reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in New York City. Syphilis is a disease that has been documented for hundreds of years. Following a famous outbreak reported in 1494 in Europe, the poet Fracastoro wrote about the afflicted shepherd, Syphilus, in 1530. Also one must never forget the Tuskegee experiments documenting the natural history of syphilis in uninformed African-Americans that ran for a shocking thirty years between 1932 and 1962. Though Fleming discovered penicillin in 1943, and Mahoney and Moore showed it was effective against syphilis in 1946, the study subjects at Tuskegee didn’t receive this curative therapy until 1962. The last syphilis epidemic in the United States occurred between 1986 and 1990, after which rates began to steadily drop to an all-time low in 2002.

Syphilis has now made a comeback in NYC, with the DOH reporting twice as many primary and secondary syphilis cases in the first quarter of 2007 (260 cases) as compared to the same period last year (128 cases). 96% of cases were among men with a median age of 34 years, with the neighborhood of Chelsea holding the highest number of cases. The increase in syphilis cases is noted particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM), a trend that has been seen in other large U.S. cities. Of deeper concern is the fact that an increase in syphilis cases can precede an increased rate of HIV infection, since these infections are transmitted in a similar fashion but syphilis has a shorter incubation period. Also, the number of women with syphilis in New York has risen from three in the first quarter of 2006 to ten for the same period in 2007, raising concern that congenital syphilis will reemerge.

Clinically, there are three stages of syphilis: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary syphilis, which appears three days to three months and on average, three weeks, post exposure, presents as a chancre: a painless ulcer at the site of inoculation, usually at the genital region, anus or mouth that resolves within a few weeks and may be accompanied by painless regional lymphadenopathy. Secondary syphilis occurs when the infection has become generalized and presents two weeks to two months after the primary chancre, and occasionally concurrent with, the primary lesion. It consists of symmetrical pink, non-pruritic macules on the trunk, palms and soles of the feet and which may coalesce in intertriginous areas to form wart-like white lesions termed condylomata lata. These rashes may be accompanied by generalized lymphadenopathy, mucosal ulcers and involvement of other systems. After this second stage, the infection becomes dormant or “latent†for a number of years before progressing to tertiary or quarternary syphilis. Tertiary syphilis presents two or more years after infection, with gummas – most commonly of the skin, bone, liver, cardiovascular system, and brain. Neurosyphilis may be characterized by meningovascular disease and parenchymal disease including tabes dorsalis and general paresis.

Early syphilis is treated with simple IM injections of long-acting benzathine penicillin G (“Bicillin L-Aâ€, not the “C-R†type): 2.4 million units once for exposed persons or early disease (less than 2 years since exposure ie primary, secondary or early latent disease). For late latent disease (more than two years since exposure or unknown time period,) 2.4 million units weekly for 3 weeks. Patients in whom neurosyphilis is suspected need a lumbar puncture, and if there is evidence of disease, require IV treatment: 3-4 million units IV every 4 hrs or continuously for 10 – 14 days. In HIV positive patients, the diagnosis of neurosyphilis is more difficult, and false negative CSF-VDRL tests occur frequently enough to warrant empiric treatment when clinical suspicion is high enough.

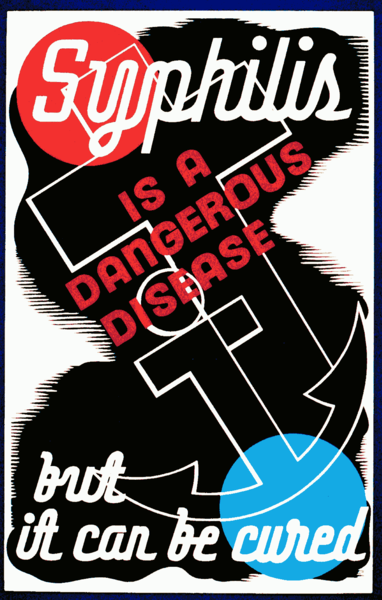

While syphilis may wreak havoc on the body, it is astonishingly treatable and along with patient education, we as doctors have a significant role to play in curtailing this disease:

•Assess who is at risk. Perform a full sexual history and detailed exam on every patient.

•Screen for syphilis in patients newly diagnosed STDs, sexually active persons with HIV, partners of people with syphilis, and men who have sex with men. Most institutions screen with a non-treponemal test (RPR), but Bellevue begins with a treponemal specific IgG serology followed by a reflex non-treponemal RPR titer. Few institutions have the capacity to perform darkfield microscropy anymore. Remember that a new STD diagnosis indicates screening for other STDs, including HIV.

• Diagnose primary and secondary syphilis clinically (risk factors, suspicious lesions) and send lab tests to support the diagnosis. Tertiary and quarternary syphilis must be considered in a variety of clinical presentations. The CDC updated treatment guidelines in 2006, published here: http://www.cdc.gov/std/default.htm.

• Report cases of syphilis to the NYCDOHMH (212-788-4443).

• Educate your patients to use condoms and practice safe sex. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/std/std2.shtml, provides a number of services such as free testing regardless of health insurance or proof of citizenship.

By considering the “Great Imitator†in our differential and improving patient education and outreach, we can prevent this curable infectious disease from returning on an even greater scale.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Poster for treatment of syphilis, showing a man and a woman bowing their heads in shame. Created/Published: Rochester, N.Y.: WPA Federal Art Project, between 1936 and 1938.