Commentary by Daniel Frenkel, PGY-2

Commentary by Daniel Frenkel, PGY-2

Case: A 46 year old male with diabetes on oral hypoglycemic medications is admitted to the hospital with one day of constant epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate oral intake. You are concerned about pancreatitis but laboratory analysis reveals amylase levels that are within the normal reference range. You notice that his glucose level is 410mg/dL and that the specimen is described as lactescent. Should you still be concerned about acute pancreatitis?

Lactescent or lipemic blood samples are indicative of elevated fatty substances usually in the form of triglycerides. Such samples may interfere with amylase assays and produce false negative results to the extent that acute pancreatitis may actually be the correct diagnosis in a patient with normal amylase levels. While gallstones and alcohol account for roughly 80% of cases of pancreatitis, hypertriglyceridemia is the next most common etiology, accounting for roughly 1-4% of cases (sometimes noted up to 7%). An association between elevated triglyceride levels and pancreatitis exists where mild to moderate elevations are considered to be an epiphenomenon, while elevations greater than 1,000mg/dL can lead to pancreatitis. Despite the frequency of hypertriglyceridemia causing pancreatitis, it remains unclear how to predict which patients with triglyceride levels greater than 1,000mg/dL will actually develop this disorder.

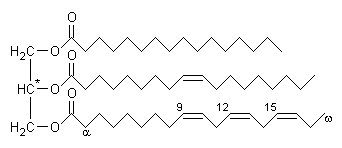

Similar to cholesterol, triglycerides have both exogenous and endogenous sources. When triglycerides are obtained from dietary sources they are initially packaged in chylomicrons while endogenous triglycerides synthesized by the liver are packaged in VLDL. These two lipoproteins are the predominant source of triglycerides in blood and interact with lipoprotein lipase in peripheral tissue in order to store triglycerides in muscle and adipose tissue. Therefore, the development of hypertriglyceridemia is dependent on a balance between the synthesis and catabolism of these lipoproteins. Primary hypertriglyceridemia is a category of rare hereditary diseases that can cause elevated triglycerides which include Familial Chylomicronemia (Type I Hyperlipidemia), Familial Hypertriglyceridemia (Type IV Hyperlipidemia), and Familial Combined Hyperlipidemia (Type V Hyperlipidemia). Secondary hypertriglyceridemia has numerous common etiologies such as alcohol, diabetes, diet, obesity, estrogen, pregnancy, CRF, hypothyroidism, and drugs (thiazides, beta-blockers, protease inhibitors). The primary hereditary disorders are capable of producing triglyceride levels greater than 1,000mg/dL, while secondary causes require a baseline defect in triglyceride catabolism which is then subjected to the precipitating insult to achieve similar levels.

Why do elevated triglycerides cause acute pancreatitis? The exact mechanism is unclear but it is thought to involve increased concentrations of chylomicrons in the blood. Chylomicrons are usually formed 1-3 hours post-prandially and cleared within 8 hours. However, when triglycerides levels exceed 1,000mg/dL, chylomicrons are almost always present. These low density particles are very large and may obstruct capillaries leading to local ischemia and acidemia. This local damage can expose triglycerides to pancreatic lipases. The degradation of triglycerides to free fatty acids can lead to cytotoxic injury resulting in further local injury that increases inflammatory mediators and free radicals, eventually manifesting as pancreatitis.

The opening case describes a patient with worsening diabetes and likely elevated triglycerides who developed pancreatitis. Hyperlipidemic pancreatitis in the acute setting should be managed in a similar fashion to the treatment of many other causes of pancreatitis; supportive care including bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and analgesia should be supplied as needed. One should always confirm that the triglycerides levels are truly elevated. Additional testing should be directed at identifying the inciting cause for the elevated triglycerides (such as basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, urine protein, and TSH levels). Any secondary cause (i.e. diabetes, drug, hypothyroidism, etc.) should always be treated acutely as this may help resolve the hypertriglyceridemia and lowering triglycerides levels is shown to improve the clinical course of the pancreatitis.

Although triglycerides levels decrease naturally from fasting and bowel rest over a period of days, there have been attempts at accelerating this process. One such method is the direct removal of lipoproteins by plasmapharesis which has been used as prophylaxis in patients unresponsive to drug therapy. However, this method is expensive and limited to large medical centers. An alternative approach is to directly remove lipoproteins to enhance their catabolism. This method is based on observations that hypertriglyceridemia is caused by a direct lipoprotein lipase deficiency or decreased activity. Lipoprotein lipase activity is enhanced by both heparin and insulin which has prompted a handful of case reports using these two agents intravenously in the acute treatment of pancreatitis and lowering of triglycerides. While neither of these techniques have formal guidelines, insulin should be used for brittle diabetes to aid in lowering triglyceride levels. In contrast to these more exotic approaches, one can also use simple triglyceride lowering medications such as fibrates or niacin to decrease triglyceride levels.

Further workup includes investigating underlying defects in metabolism that may be classified as a familial disorder. A thorough family history and genetic testing should be obtained if indicated and this task may require the assistance of a lipid specialist. For long term management, triglycerides levels should be maintained below 500mg/dL to prevent a recurrent pancreatitis.

Check back with Clinical Correlations for another post detailing the general management of hypertriglyceridemia…

References:

1. Yadav D. and Pitchumoni C.S. “Issues in hyperlipidemic pancreatitis.†Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2003; 36(1): 54-62.

2. Gan S.I., et al. “Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis: A case-based review.†World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006; 12(44): 7197-7202.

3. Kasper D.L., et al. Harrison’s Online: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th Edition. The McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. 2007, Chapter 335. [www.accessmedicine.com]

4. Alagozlu H., et al. “Heparin and insulin in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia-induced severe acute pancreatitis.†Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2006; 51: 931-933.

7 comments on “Why Does Hypertriglyceridemia Lead to Pancreatitis?”

Thanks!

I have always wondered why hypertriglyceridemia caused pancreatitis.

Thanks, now that that question was answered, I am curious how beta-blockers and TSH may cause pancreatitis….and the research continues….love this site 🙂

A very didactic presentation on the facts.

I would actually consider chylomicronemia syndrome in this case given the normal amylase and list pancreatitis as a differential.

High serum triglyceride levels interfere with the assays for serum amylase and lipase, therefore the amylase result for this patient is uninterpretable. A better test would be urinary amylase in a case like this.

This is extremely helpful. After being hospitalized for 3 times in the past for pancreatitus, 2001 – 2007, the Hospital lab never ever knew the reason why. I guess it was before this research. The last time I had eaten a 2 pound bag of M&M peanuts over a two day period prior to the onset of pain. I had told them that. This may have spiked my triglycerides perhaps. They never made the connection even after 2 weeks and over 30 viles of blood for testing.

Comments are closed.