Faculty Peer Reviewed

In the fall of 2010, after Haiti was razed by a magnitude 7.2 earthquake that left over 316,000 people dead, cholera was injected into the tumult to add to the growing list of Haiti’s struggles [1]. Cholera is an ancient scourge whose origins are believed to come from the Ganges River delta of India [2]. It affects up to 5 million people worldwide, with over 100,000 deaths per year [3]. The cholera outbreak in Haiti was unexpected in that Haiti had not had cholera for over 100 years [4]. As of January 2011, it has already infected over 200,000 people and killed at least 4,000 people [5].

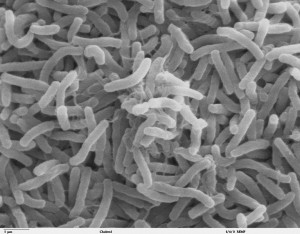

Vibrio cholerae is a curved Gram-negative rod with a single flagellum [6]. After toxigenic strains of V. cholerae are ingested, there is an incubation period of about 18 hours to 5 days before the diarrheal illness ensues [2]. The bacteria have to survive the harsh acidic gastric milieu and make it to the small intestines, where they propel themselves with their flagella through the thick mucus lining of the gut [2]. When they reach the epithelial cells, they attach themselves and rapidly proliferate [2]. They do not invade the epithelial cells, rather they release their classic enterotoxin in high concentrations directly onto the mucosal cells [2]. A subunit of the cholera toxin is transported into the epithelial cell where it stimulates adenylate cyclase to increase cyclic AMP, which ultimately causes active secretion of sodium and chloride [6]. This leads to a massive osmotic outpouring of sodium, chloride, potassium and bicarbonate that overwhelms the absorptive capacity of the bowel and results in severe watery diarrhea [2]. The typical “rice water stool†of cholera patients is loaded with V. cholerae and is highly infectious [2].

The treatment of cholera’s deadly desiccating diarrhea involves prompt rehydration with electrolyte-rich oral or intravenous rehydration solutions. Antibiotics, most frequently doxycycline, can also be used to shorten the duration and severity of the diarrhea [2]. But prevention is the key, with the focus on clean water, sanitation and efficient surveillance systems in place to halt budding outbreaks. There is also an oral, inactivated whole cell cholera vaccine that has shown to be up to 80% effective, but it is unclear whether it is a cost-effective and sustainable prevention measure [2].

Large scale outbreaks of cholera have been frequent in the last few centuries, with seven major pandemics recognized since the 1800s. The first six pandemics all originated in India, and were due to the “classic†V. cholerae biotype [7]. However the seventh pandemic, which began in 1961 in Indonesia and is still on-going, is predominantly due to the new “El Tor†biotype. It was first isolated at a quarantine station in 1905 from Indonesian pilgrims in the town of El Tor, Egypt [2]. The particular strain of V. cholerae that is currently in Haiti is further distinguished by several genetic polymorphisms that appear to make it more virulent than many previous cholera strains [4]. It can survive longer in the human host and induce more diarrhea, thus it is able to disseminate faster and more broadly than other strains [4]. This new strain is not only more fit, it also appears to have developed more antibiotic resistance than other strains [4]. There is great concern that this hardier and deadlier strain will not only continue to batter Haiti, but it may also establish itself throughout the Americas.

So where did this cholera strain come from? Is it domestic or imported? Through DNA sequencing of V. cholerae strains, it appears that the Haitian outbreak strain is nearly identical to the El Tor strain that is endemic to South Asia [4]. It is distinct from the circulating V. cholerae strains in Latin America. Cholera can actually be a part of normal estuarine flora, known to cling to zooplankton in brackish waters, so some have claimed that the cholera outbreak was home-grown [2]. Climatic and meteorological phenomena can create conditions favorable to the growth and spread of V. cholerae, which could cause an outbreak [4]. However, the genetic similarity of the Haitian strain and South Asian strains of V. cholerae makes it most likely that the V. cholerae was imported [4].

This news was met with much consternation by the United Nations, as it indirectly implicates Nepalese UN forces who were working in the interior of Haiti. The first cases of cholera were reported near the town of Meille, which was the location of a large UN camp of Nepalese peacekeepers [8]. It was reported that a septic tank inside the UN camp was draining into a local stream that provided drinking water to the community [8]. Cholera is endemic to Nepal, so the Nepalese peacekeepers were singled out as the carriers. This was believed to be the source of the contamination of the Artibonite River, the longest and most important river in Haiti. There have since been many protests against the Nepalese and UN presence, and some have called for their expulsion.

Many experts feel that this outbreak could swell to over half a million people over the next year alone [9]. The lack of infrastructure in Haiti, along with the fact that the current Haitian population has never been exposed to cholera before, creates an unfortunate and precarious scenario without any clear solutions [9]. Antibiotics are often reserved for only severe cases of cholera, but there have been discussions to broaden the coverage to include cases of both moderate and severe diarrhea to help curtail the shedding of V. cholerae and reduce secondary infections [10]. But antibiotics are costly and there is the ever-present specter of antibiotic resistance to consider. There are also plans for a large scale vaccination program which has been met with much skepticism. Critics point out that there is a limited supply of the vaccine, it is unproven on such a large scale, and it will be very cumbersome to organize such a massive campaign throughout the ravaged districts of Haiti [11]. However, the key to controlling cholera lies in basic preventive measures centered on education, improved sanitation and access to clean drinking water. All agree that cholera has established itself in Haiti, and cases have already been reported in the neighboring Dominican Republic and Florida [12]. This unwelcome old foe that has fallen into Haiti’s lap is here to stay, and a committed, measured and coordinated response is needed to keep this pestilence at bay.

Dr. Matt Johnson is a former NYU internal medicine resident and current Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer, Oklahoma State Department of Health

Peer reviewed by Howard Leaf, MD, Infectious Diseases, Medicine, NYU School of Medicine

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

1. Schiermeier Q. Quake Threat Looms over Haiti. Nature. 2010; 467: 1018-1019. [PMID 20981064]

2. Sack DA et al. Cholera. Lancet. 2004; 363: 223-233. [PMID 14738797]

3. Cholera Vaccines. A Brief Summary of the March 2010 Position Paper. World Health Organization. 2010. http://www.who.int/immunization/Cholera_PP_Accomp_letter__Mar_10_2010.pdf

4. Chin CS et al. The Origin of the Haitian Cholera Outbreak Strain. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364: 33-42. [PMID 21142692]

5. Tuite AR et al. Cholera Epidemic in Haiti, 2010: Using a Transmission Model to Explain Spatial Spread of Disease and Identify Optimal control Interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011; Epub ahead of print. [PMID 21383314]

6. Gladwin M, Trattler B. Clinical microbiology. Miami, FL: MedMaster, Inc. 2004.

7. www.cbc.ca/news/health/story/2008/05/09/f-cholera-outbreaks.html

8. Enserink M. Despite Sensitivities, Scientists Seek to Solve Haiti’s Cholera Riddle. Science. 2011; 331: 388-389. [PMID 21273460]Â http://pubget.com/paper/21273460

9. Butler D. Cholera Tightens Grip on Haiti. Nature. 2010; 468: 483-484. [PMID 21107395]

10. Nelson EJ et al. Antibiotics for Both Moderate and Severe Cholera. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364: 5-7. [PMID 21142691]Â http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21142691

11. Cyranoski D. Cholera Vaccine Plan Splits Experts. Nature. 2011; 469: 273-274. [PMID 21248807]

12. Harris JB. Cholera’s Western Front. Lancet. 2010; 376: 196

One comment on “Cholera in Haiti”

Comments are closed.