Commentary by Jatin Roper MD PGY-3 and Christine Ren MD Associate Professor, Department of Surgery

Commentary by Jatin Roper MD PGY-3 and Christine Ren MD Associate Professor, Department of Surgery

Bariatric procedures to treat obesity involve the restriction of the gastric reservoir, bypass of part of the gastrointestinal tract, or both. Worldwide, an estimated 300 million people are obese, and in the United States, the percentage of adults who are obese increased from 15% in 1995 to 24% in 2005. (Obesity is defined as a Body Mass Index or BMI of 30 or more, measured as kg / m2; for example, a woman 5 feet, 4 inches tall weighing 175 pounds.) Obesity is associated with, but not limited to, increased risk of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, several forms of cancer, and depression, as well as decreased quality of life.

Non-surgical therapy for obesity

Therapy for obesity has included dieting, exercise, and medications. However, reduction in caloric intake combined with exercise typically results in 5-10% reduction in weight (roughly 10-15 pounds) over a number of months, which is rarely sustained. There are no truly effective pharmacologic therapies for obesity; the only currently FDA-approved compounds, sibutramine (trade name Meridia), orlistat (trade name Xenical), and phentermine are limited by side effects and rebound weight gain after discontinuation.

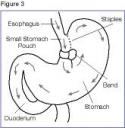

Types of bariatric surgery

Surgical modalities of bariatric surgery can be grouped by their intended physiologic effects: Vertical-banded gastroplasty and adjustable gastric banding involve gastric restriction, while jejunoileal bypass and bilio-pancreatic diversion induce malabsorption; Roux-en-Y gastric bypass contains components of both of these basic types. Adjustable gastric banding and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass are now the favored procedures, and are often performed laproscopically. In gastric banding, a band is placed around the proximal portion of the stomach. In gastric bypass, the stomach is divided into a small proximal gastric pouch and the remaining main stomach is bypassed. The gastric pouch is connected to the small bowel by a jejunal segment, called a Roux limb.

Clinical evidence

A meta-analysis of 136 studies involving 22,094 patients by Buchwald et al. (JAMA 2004;292(14):1724-37) found a peri-operative mortality of 0.1% of purely restrictive procedures and 0.5% for gastric bypass. Almost all patients pooled in the study were followed for approximately two years. Bariatric surgery resulted in resolution of co-morbidities such as diabetes (77% of patients), hypertension (62%), hyperlipidemia (70%), and obstructive sleep apnea (86%). They report an overall excess weight loss of 48% for gastric banding and 62% for gastric bypass.

O’Brien et al. (Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):625-33) randomized 80 obese patients (BMI 30-35) to laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or an intensive low-calorie (500-550 kcal/day) diet using Optifast packets with orlistat therapy. At two years the surgical group lost 22 percent of initial weight while the non-surgical group lost 6 percent of initial weight (P<0.001). This is the only randomized study of bariatric surgery versus medical therapy, and one of the few to report efficacy of bariatric surgery in patients with mild to moderate obesity.

The Swedish Obese Subjects Study (N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):741-52) prospectively studied 2,010 obese patients (mean BMI 41.8 ±4.4, minimum BMI of 34 for men and 38 for women) undergoing vertical-banded gastroplasty, adjustable gastric banding, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass compared to 2,037 matched controls who received conventional treatment. After a mean of 10.9 years adjusted mortality was significantly lower in the surgical group (hazard ratio for mortality 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54-0.92; P=0.01, absolute risk reduction=1.3%, NNT=76). Weight lost compared to total initial weight was 14% for the gastric banding group, 25% for the gastric bypass group, and negligible for the control group. One limitation of the study is that a majority of patients underwent vertical-banded gastroplasty, a restrictive procedure that has largely been replaced by laparoscopic gastric banding.

Mechanisms of weight loss

Intuitively, procedures such as gastric banding and gastric bypass are thought to result in weight loss by restricting the gastric volume that can accept food. Though this may be partially true, patients report decreased, rather than increased, hunger shortly following surgery, and do not eat more often to compensate for the diminished gastric reservoir. Cummings et al. (N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1623-30) found that levels of ghrelin, a hunger-inducing hormone produced by the stomach, greatly decreased following gastric bypass but increased following diet-induced weight loss. A majority of subsequent studies confirmed these findings in gastric bypass, but data from our own group suggest than ghrelin levels do not significantly change following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (Shak et al. Gastroenterology 2007;132(4) Suppl. 2). Interestingly, glycemic control in diabetic obese subjects improves within days to weeks following both gastric banding and bypass well before weight loss occurs. At least in the case of gastric bypass, this may be due to increased secretion of GLP-1, an insulin secretegogue, by the gut; increased release of PYY following surgery may also facilitate weight loss (le Roux et al. Ann Surg. 2006;243(1):108-14). If bariatric surgery does in fact modulate hormones involved in energy homeostasis, these mechanisms may one day be exploited in the development of pharmacologic therapies for obesity.

Patient selection and evaluation

In 1991 the National Institutes of Health established guidelines for the surgical treatment of obesity, now known as bariatric surgery: body mass index or BMI ≥40 or ≥35 with significant co-morbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea, severe diabetes type II, or obesity-related cardiomyopathy. Prospective surgical candidates were advised to first attempt weight loss with dieting and exercise. These recommendations precede the development of safer laparoscopic techniques and reports from large cohort studies (discussed above) on the lasting beneficial effects of bariatric surgery.

Due to the behavioral and emotional changes that may occur after bariatric surgery, pre-operative and on-going psychological therapy is recommended. Patients should be educated on realistic weight-loss expectations, possible complications, and the need for long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

We believe six conclusions can be drawn from the current literature on bariatric surgery:

1. Obesity is a significant public health concern, and bariatric surgery is the only therapy shown to reduce obesity-associated mortality. As surgical techniques improve and greater numbers of procedures are performed laproscopically, we expect greater improvements in outcomes.

2. Weight loss following bariatric surgery is sustained and substantial (14 – 25% over 11 years).

3. Bariatric surgery results in effective treatment, and often cure, of obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, and hypertension. In fact, bariatric surgery is likely the most effective therapy for Type II diabetes in the obese.

4. Bariatric procedures are, in general, safe, with perioperative mortality rates of 0.1% or less.

5. Though there are few contraindications to bariatric surgery, evaluation should include psychological assessment and review of medical co-morbidities.

6. Patients with BMI greater than 30 with or without co-morbidities should be referred for evaluation for bariatric surgery, without requirement of a lengthy trial of dieting and exercise.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

2 comments on “Treatment of obesity with bariatric surgery: evidence and implications”

I think the most exciting about this surgery is the fact that type 2 diabetes appears to resolve shortly after the intestinal bypass procedures, even before any significant weight loss occurs. There have been studies on rats that indicate this may be due to the bypass of the duodenum and a short part of jejunum. A recent study from Brazil (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007 Mar-Apr;3(2):195-7 shows some very preliminary work in humans and reference to the clinical trials web site of the FDA reveals that a study in being done at a small community hosital in Westchester. Certainly if type 2 diabetes proves to be a “surgical disease” it would surely be quite qa change from present Rx. I would be interested in what Drs. Rooper & Ren think about this approach and if they plan to do any study at NYU.

Very nice review. Please be aware that the Med/Surg conference at 5:00 PM on November 29 will focus on obesity and bariatric surgery at Bellevue Hospital Center.

Comments are closed.