Peer Reviewed

What medications do you currently take? Do you have any allergies? What medical conditions did your parents live with, or die from?

As physicians in training, we are conditioned to drill every patient with a standard list of questions whose answers could literally save a life. We investigate for drug toxicities, medication interactions, daily exposures, and family histories that shed light onto present illness.

Within our standard interview we also check off mandatory boxes to describe a patient’s “Social History”—Do you smoke cigarettes? Drink alcohol? Use drugs? Have sex?—however we are not always trained to see our patients as social beings. We are not always prompted to ask another, crucial set of questions that could just as easily save a life as uncovering heart disease history:

Do you live alone? Who will visit you here in the hospital? With whom do you share your private worries and fears? How much of your week do you spend with other people?

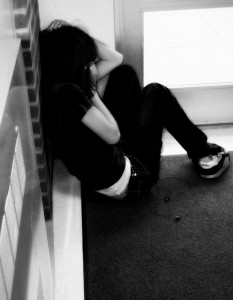

In other words: Are you lonely? These questions can feel unusual, if not uncomfortable, for practitioners who lead rich social lives and have familial support, and may never think twice about loneliness as an epidemic. And yet all of us have surely encountered patients who are not only lonely inside the hospital walls—no visitors, no collateral from next of kin—but whose isolation likely led to them being hospitalized in the first place.

What role, exactly, does loneliness play in the pathophysiology of a patient’s disease course? We’ve all learned about the anti-anxiolytic effects of our body’s innately programmed mechanisms for social affiliation: once activated, our oxytocin and medial pre-optic hypothalamic pathways can lead to stronger defenses against the damaging effects of stress. But the evidence for loneliness as a pathogen penetrates much deeper than our basic neuro-hormonal networks. This growing body of research has identified social isolation as an independent driver of maladaptive immune activity,[1] worsening cardiovascular disease,[2] and all-cause mortality.[3]

Over the past decade, researchers have started to identify more precise molecular pathways by which isolation takes its toll. There is evidence that individuals who chronically experience social isolation develop impairments in the transcription of glucocorticoid response genes, and have subsequent flares in the activity of pro-inflammatory transcription control pathways,[4] due to beta-adrenergic activation of GATA1 at the interleukin-6 locus.[5] It has also been found that plasmacytoid dendritic cells and monocytes are the source of “loneliness-associated genes” in chronically isolated people,[6] specifically the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, NF-κB, in monocytes.[7]

From these results we should extend our thinking to wonder: without any interventions, might our patients who experience chronic loneliness go on to experience worsening of their medical conditions, in the same way an untreated infection will eventually lead to sepsis? And if so, what does that mean for physicians, whose responsibility it is to care for a patient’s full health? Aside from being able to “prescribe” social interaction,[8] there is some evidence to suggest that even in our short clinic and hospital encounters we can improve a patient’s sense of isolation, and subsequently improve their health. One study in 2006 examined a group of patients with depression; all were given placebo medications, half of them by a doctor who provided no emotional support, and half of them by a physician trained to express empathy and concern for the patients’ welfare. Patients with empathetic doctors ended up experiencing fewer symptoms of depression. Powerfully, the authors suggested, “The health care community would be wise to consider the psychiatrist not only as a provider of treatment, but also as a means of treatment.”[9]

Beyond the field of psychiatry this notion still rings true. A meta-analysis of the impact of psychotherapy on adults with irritable bowel syndrome found that patients who engaged in therapeutic conversations with their doctors, compared those who took medications only, experienced fewer symptoms (less bloating, diarrhea, constipation), not only immediately after talk therapy, but for up to a year afterward.[10] Another study examined patients with the common cold, and found that patients whose doctors demonstrated high levels of empathy (following a standard empathy “script”) experienced significantly reduced severity and duration of their colds, with more robust immune system responses.[11]

If therapeutic relationships between physician and patient have the power to improve a patient’s health, why are they not made mandatory, just as we keep stringent protocols for stroke alerts or sepsis? Likely because relationships are a bit easier said than done, in the same way that much else in clinical medicine is easier done than said. Explaining how the pathophysiology of intercellular calcium ion exchange can influence heart contractions is far more complicated than placing an ultrasound wand on a patient’s chest to see it pump. Conversely, it feels like common sense to acknowledge that being kind, warm, and empathetic to a patient could improve their care, but it is difficult to implement empathy and patience on a daily basis, in the midst of an endless to-do list, a bevy of patients with urgent needs, in a obstacle-ridden healthcare system not always designed for optimizing effective communication.

The challenge of building strong, therapeutic relationships with patients is one we all face everyday in our clinical environments. It’s not always an easy task—and it may not cure a patient’s loneliness—but if we’re up for making a connection, we could be making a powerful contribution to our patients’ healing processes.

Dr. Katherine Otto is a 4th year medical student at NYU Langone Medical Center

Peer reviewed by Anthony Grieco, MD, internal medicine, NYU Langone Medical Center

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

[1]. Olsen RB, Olsen J, Gunner-Svensson F, Waldstrøm Bxxcv v. Social networks and longevity. A 14 year follow-up study among elderly in Denmark. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(10):1189-1195.

[2]. Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(8):836-842. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19661189

[3]. Tilvis RS, Laitala V, Routasalo P, Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH. Positive life orientation predicts good survival prognosis in old age. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(1):133-137. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21764146

[4]. Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8(9):R189. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17854483

[5]. Cole SW, Arevalo JM, Takahashi R, et al. Computational identification of gene-social environment interaction at the human IL6 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5681-5686.

[6]. Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Cacioppo JT. Transcript origin analysis identifies antigen-presenting cells as primary targets of socially regulated gene expression in leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3080-3085.

[7]. Creswell JD, Irwin MR, Burklund LJ, et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(7):1095-1101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3635809/

[8]. For an extended discussion on this concept, and additional research about loneliness and health, please see: Hafner K. Researchers confront an epidemic of loneliness. New York Times. Sept 6, 2016:D1. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/06/health/lonliness-aging-health-effects.html?_r=0

[9]. McKay KM, Imel ZE, Wampold BE. Psychiatrist effects in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 2006;92(2-3):287-290.

[10]. Laird KT, Tanner-Smith EE, Russell AC, Hollon SD, Walker LS. Short-term and long-term efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(7):937-947. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26721342

[11]. Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Varrett BP, Chewning BA, Craig BM, Niu M. Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):494-501. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19582635

3 comments on “Does Loneliness Contribute to Morbidity and Mortality?”

This is a well reasoned and well written assessment of a relatively unexplored aspect of the physician-patient relationship.

I think much of what you have described could apply equally to medical students, house staff and practicing physicians who also experience loneliness and inability to establish meaningful social relations. The gulf between physicians and their patients is a gulf from both sides. The high rates of depression, “burn out” and substance abuse (including alcohol, may reflect this social isolation.

Great that you focused on an essential but ignored dimension of care. Difficult to quantitate, but so are many non-metric experiences both within and without our life in medicine; the sub-clinical (pre-clinical ?) molecular dimensions you’ve referred to not withstanding. I wonder how you identified this topic and pulled together the diverse references into a unified thesis. Excellent.

Congratulations on a concise, comprehensive, piece that shows how evidence-based medicine is not limited to the correct and timely application of trial results, but rather extends to all psychosocial and contextual dimensions of the patient’s illness. The therapeutic value of a good patient-doctor relationship, has been recognized from the beginning of the history of medicine worldwide. Yet, it has often been discarded as subjective and non-measurable. With the increasing support of laboratory findings and clinical studies, we may improve our ability to learn it, practice it and teach it. I also agree that reducing patients’ loneliness through empathic bidirectional communication will also contribute to our wellbeing as physicians.

Comments are closed.