Commentary By Sandra D’Angelo, PGY-3

Commentary By Sandra D’Angelo, PGY-3

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women, second only to lung cancer as a leading cause of death from cancer. Experts state that approximately 210, 000 women will be diagnosed in 2006 and about 40,000 will die from the disease.1 According to data compiled by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute, 61% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed while the cancer is still confined to the primary site (localized stage); 31% are diagnosed after the cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes or directly beyond the primary site; 6% are diagnosed after the cancer has already metastasized (distant stage) and, for the remaining 2%, the staging information was unknown. The corresponding 5-year relative survival rates were: 98.1% for localized; 83.1% for regional; 26.0% for distant; and 54.1% for unstaged.2 Therapy is directly dependent upon the stage of diagnosis. In addition, estrogen, progesterone and her2 neu status also play a major role in determining the appropriate therapy. The attached table briefly summarizes treatment based on stage.

Recently, the New York Times reported on the FDA approvalal of Mammaprint, an in vitro multivariate index assay that measures 70 gene markers in tumors. The information is then used to calculate an index to predict the likelihood of recurrence or metastasis. This test is not for everyone; in fact, it was only approved for woman who are under age 61, with stage I and II disease, tumor size <5cm and node negative disease.

Approximately 100,000 women are diagnosed with early stage disease each year. Often times, whether or not to use adjuvant chemotherapy in this setting is a diagnostic challenge. Frequetnly, there is significant morbidity associated with these toxic agents. Nonetheless, the benefit is clearly evident. The goal of this test is to help oncologists customize treatment based on a patient�Ѣs specific calculated risk. However, this test is far from a perfect test. The positive predictive value at five years was 23% and 29% at 10 years. The negative predictive value was 95% at 5 years and 90% at 10 years. In other words, 23% of women classified by this test as high risk had a recurrence somewhere in their body within 5 years, while only 5% classified as low risk had a recurrence in 5 years.

This isn�Ѣt the first of these tests. The Oncotype Dx assay is an RNA based multigene assay that measures expression of 16 breast cancer-related genes and uses the expression pattern to determine a recurrence score (RS) in woman who are estrogen +, but node negative. In the NSABP B-20 chemotherapy benefit study, 651 patients demonstrated that breast cancer patients with high recurrence scores have a large benefit from chemotherapy. Patients with low recurrence scores had minimal benefit from chemotherapy. This assay is commercially available, but its utility is still controversial because there is no prospective randomized trial that has been completed. However, the TAILORx trial, led by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, is currently in progress and will address this very issue.

Finally, gene micro array assays are also being used to analyze estrogen receptor and Her-2/neu status, as reported in a recently published article in Lancet Oncology on February 15, 2007. The Affymetrix U133A Gene Chip had an overall accuracy ranging from 88%-96% for estrogen receptor status and 89%-93% for confirming Her-2/neu status. This allows for quantitative data that is not provided when using immunohistochemical or fluorescence in-situ hybridization tests. For example, the higher the level of estrogen expression may presumably be translated to higher benefit from hormonal therapy.

Thus, these new evolving technologies will continue to allow human genes to be studied and ultimately determine their role in the development of cancers, leading to the identification of new diagnostic and prognostic markers. They may soon allow us to tailor our decisions about therapy on a case by case basis after looking at multiple prognostic genetic markers.

References:

1 Jemal A et al.; Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006 Mar-Apr;56(2):106-3

http://sfx.med.nyu.edu/sfxlcl3?genre=article&id=pmid:16514137&_char_set=utf8

2. NCI website: http://www.cancer.gov/

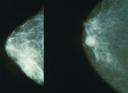

Picture Courtesy of Wikimedia