A 70 year old man with a history of prostate cancer, status post radiation treatment in August 2003, a history of abdominal surgery for unknown reasons, and a history of heavy alcohol use was seen at the VA. The patient was referred for a complaint of bright red blood per rectum and was incidentally noted to have elevated liver enzymes.

A 70 year old man with a history of prostate cancer, status post radiation treatment in August 2003, a history of abdominal surgery for unknown reasons, and a history of heavy alcohol use was seen at the VA. The patient was referred for a complaint of bright red blood per rectum and was incidentally noted to have elevated liver enzymes.

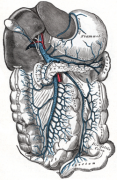

Colonoscopy revealed blood in the rectosigmoid, dilated vessels in the rectum and angioectasia, thought to be secondary to the radiation therapy. In addition, the patient had a right upper quadrant ultrasound with Doppler, which revealed a thrombosis of the

main portal vein beginning at the confluence and extended to involve its major hepatic branches. Prominent collateral vessels suggested a chronic process. The distal most splenic vein was also thrombosed. A large collateral vessel was seen anterior tothe native splenic vein and was also thrombosed. The liver was enlarged and demonstrated a heterogeneous echotexture. No discrete large hepatic masses are noted. There was no ascites.

Question: How should you approach this incidental but important finding?

Commentary By: Michael Poles, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Associate Editor Clinical Correlations,

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is not an uncommon diagnosis on our hospital wards and in our clinics. PVT represents thrombosis development within the extrahepatic portal venous system that drains the liver. Occasionally thrombosis can involve the superior mesenteric vein. Local and systemic factors may be associated with development of PVT as noted below:

Cirrhosis Hypercoagulable states

Malignancy Malignancy

Schistosomiasis Sepsis

Pancreatitis Drugs such as oral conraceptives

Post-surgical Pregnancy

Portal vein compression, such as by local lymph nodes

Systemic factors, especially hypercoagulable states are responsible for 60% of cases and local factors, only 40%. It should be noted that cirrhosis is an increasingly common cause of PVT, especially with decompensated disease. This occurs despite the typical coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia that accompanies end-stage cirrhosis. The risk is increased significantly more if the patient also has a hepatocellular carcinoma.

The etiology of PVT in our patient remains unclear. Imaging and labs, did not suggest cirrhosis. It is possible that the thrombosis occurred as a sequelae of his intrabdominal surgery, though that will be difficult to prove.

Patients with PVT typically present with abdominal pain, and at times, with nausea and fever. Occasionally, patients may present with acute onset of ascites. Involvement of the mesenteric vein may cause bowel ischemia and increased severity of symptomatology. With increased chronicity, problems related to portal hypertension may predominate, including variceal bleeding. Diagnosis is typically confirmed by imaging including color Doppler ultrasonography, CT with contrast, MRI or endoscopic ultrasound.

The goal of therapy is to reverse or prevent progression of the thrombosis and to treat the complications of the PVT. Treatment of acute PVT (often considered to be diagnosed when the patient is seen within 60 days of their symptom initiation) with thrombolytics or anticoagulation may result in recanalization of the portal vein. If recanalization occurs, treatment with coumadin should be continued for 3-6 months if a finite cause of PVT is noted, or indefinitely if a finite cause is not found. The effectiveness of thrombolysis appears to decrease beyond the initial 14 days of symptoms. While use of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients who often have baseline coagulopathy seems counterintuitive, and perhaps dangerous, it does not appear to be associated with increased risk of severe bleeding occurrences and decreases the incidence of new thrombotic episodes. Patients with varices should receive beta blockers or undergo endoscopic variceal obliteration.

Image Courtesy Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hepatic_portal_vein

3 comments on “How Should You Approach A Patient with an Incidental Finding of a Portal Vein Thrombosis?”

Distinction between acute and chronic portal vein thrombosis is critical in deciding on the appropriateness of anticoagulation and/or thrombolysis. Using any duration of symptoms as a cut-off is by nature arbitrary. A sine quinone of chronic process is presence of collaterals. Once collaterals are present, neither thrombolysis nor anticoagulation are indicated.

Another clinical pearl is that in patients without underlying cirrhosis, acute portal vein thrombosis results in no or only small amount of ascites. Even when present it is frequently transient. This is in sharp contrast with hepatic vein thrombosis, which results in massive ascites. The difference is in the pathophysiology of ascites accumulation in portal HTN. In portal HTN most of the ascetic fluid is nothing rather interstitial fluid of the liver seeping into the peritoneal cavity. Splanchnic interstitial fluid is only a minor contributor. Hepatic interstitial fluid comes from plasma leaking through the sinusoids. Consequently, any portal hypertension increasing sinusoidal pressure will result in massive ascites, while pre-sinusoidal portal HTN does not increase sinusoidal pressure and does not result in large amount of ascites. That said, if some sinusoidal HTN is already present (as seen in patients with cirrhosis) portal vein thrombosis may result in increase in the ascites or render it diuretic resistant.

Finally, do not forget intra-abdominal infection as a cause of portal (and mesenteric) vein thrombosis.

All valid points

A couple of points-of course the portal vein does NOT drain the liver as Dr. Poles states, the hepatic veins drain the liver. The correct term is sine qua non, which has nothing to do with benzoquinone (a quinone), a cyclic diene oxidizing agent.

Comments are closed.