Commentary by Josh Olstein MD, Chief Resident NYU Internal Medicine

Mr. J is a 56 year old Caucasian gentleman who presented with complaints of “I just can’t do what I used to be able to do. I just don’t have the energy.” He describes himself as a hearty fellow who had never had a problem with his energy level until around a year ago. Though he has not noticed any weight loss, he denied any weight gain despite the lumberjack-like portions he eats (no disrespect meant to the lumberjack audience). He denied any other systemic complaints. His past medical and social history is noncontributory and he does not provide any pertinent family history of illness, in particularly denying any history of neoplasia. Physical examination reveals a well-developed individual with nothing out of the normal range except some slight conjunctival pallor. Laboratory examination reveals a significant microcytic anemia and mild transaminitis. Three stool samples sent to assess for occult blood were negative. Despite this, he underwent a colonoscopic exam, which revealed a 3mm sigmoid polyp, and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which appeared normal, except for mild gastric erythema. Biopsies were taken from his gastric antrum and the mid-body, greater curve of his stomach, as well as from the normal-appearing duodenal mucosa. The histologic appearance of the gastric biopsies were normal, but the duodenal biopsies revealed severe blunting of the villi, crypt hypertrophy, with lymphocytic infiltration of the mucosa. The pathologist suggested that the findings were consistent with celiac disease, a diagnosis that was confirmed by a positive IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody. Upon repeat questioning, the patient continued to deny any gastrointestinal symptomatology.

The variability and non-specific nature of symptoms experienced by patients with celiac disease frequently lead to delayed and missed diagnoses of this common condition. As many as 85% of cases go undiagnosed and thus many patients are subject to the increased morbidity and mortality of untreated disease. Likely the largest obstacle to diagnosing celiac disease is failure to consider and test for the condition. Recently, a study published in the British Medical Journal described and validated a clinical decision tool that was highly sensitive at detecting celiac disease. Before discussing this article, let’s briefly review some of the background on celiac disease.

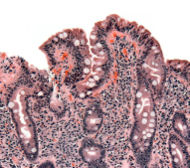

First described in 1888, celiac disease, also known as sprue or gluten- sensitive enteropathy, is an autoimmune inflammatory condition triggered by gliadin, a component of the protein gluten found in several different grains (wheat, barley and rye). The condition is most common among those with northern European ancestry but is found across the world and has a strong genetic predisposition. HLA types DQ2 and DQ8 are most commonly associated with the disease. In classic disease, continued ingestion of gluten-containing products leads to mucosal inflammation, which may result in a syndrome of malabsorption with vitamin and mineral deficiencies, weight loss, and diarrhea. Though malabsorption and diarrhea are classical features of celiac disease, patients such as the individual previously described may not experience diarrhea and may even be constipated. A multitude of diverse extra-intestinal symptoms may also predominate or complicate the clinical picture of celiac disease. Among these are neuropsychiatric disorders, iron-deficiency anemia, arthritis, osteoporosis, abnormal liver function tests, and infertility. Other disorders of autoimmunity are more frequent among people with celiac disease including Type I diabetes mellitus, thyroid and liver disease, and dermatitis herpetiformis. The associated autoantibodies, namely anti-endomysial antibodies and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies, have been well characterized and are becoming increasingly reliable aids in making the diagnosis. The “gold-standard,” however, remains small bowel biopsy. The biopsy findings of celiac disease are villous atrophy associated with intra-epithelial lymphocytes and crypt hyperplasia. It is worth noting that, given the increased incidence of selective IgA deficiency among patients with celiac disease, it is worthwhile to ensure that the patient is capable of producing IgA before serological testing for IgA anti-endomysial and IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies. The majority of patients improve with removal of gluten from the diet.

The article I mentioned earlier evaluated the characteristics of a clinical decision tool to be used to determine who should receive endoscopy with small bowel biopsy to assess for celiac disease. They prospectively included 2000 patients who were referred to receive an EGD for any reason. All patients had serology performed for anti-tissue transglutaminase (TTG) antibodies and underwent small bowel biopsy. Patients were classified as either high or low risk for celiac disease based on the presence or absence of any one of the following: weight loss, diarrhea, or anemia. Their clinical decision tool recommended small bowel biopsy for any high-risk patient or those with positive anti TTG antibodies. In total 77(3.9%) cases of celiac disease were diagnosed. The sensitivity and negative predictive value of antibody testing alone was 90.9% and 99.6% respectively. The sensitivity and negative predictive value of the clinical decision tool was 100% and 100% respectively. The results of this study suggest that small bowel biopsy of patients with a positive serology or high-risk features will capture all cases of celiac disease, and biopsy can be safely deferred among those with negative serologies and the absence of high-risk features.

As the accompanying editorial suggests, this approach will likely not alter management as most diagnostic algorithms already incorporate these factors. However, the study strongly validates our current clinical practice. As long as we consider and continue to test appropriate patients for celiac disease, the diagnosis should not elude us, and we should be able to prevent or arrest the development of significant morbidity among those who suffer with celiac disease.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

4 comments on “A Case of Celiac Disease and Diagnostic Clues”

Following the dictum of first doing no harm, I do not think there is any proven benefit in diagnosing celiac in the asymptomatic indivisual. The NIH consensus conference statement on celiac states “current data do not indicate a clear outcome benefit for early detection and treatment of asymptomatic individuals”. Thus there is no evidence that the “85%” of cases that go undiagnosed “are subject to the increased morbidity and mortality of untreated disease”. Of course they will be subject to having to follow a restricted diet and anxieties about their condition. Finally, the condition is not most common among those with northern European ancestry, but is most common among the Saharawi people in the western Sahara.

In case you didnt notice, this patient was not asymptomatic, he was anemic, fatiuged and could not gain weight appropriately to his po intake.

Therefore, the rationale for early diagnosis of celiac disease in this patient is that celiac carries increased risk of iron deficiency anemia. and it is our burden to elicit a cause. Additionally, there is an increased risk of enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (though a rare entity). That is not to mention the several associations with infertility, autoimmune disease, growth delay in children, and IgA deficiency. All valid reasons for testing an “asymptomatic” individual.

Of course in the case presented the patient is not asymptomatic. My point is that there is no proven in diagnosing the “latent” celiac. I suggest you read the NIH consensus statement on celiac which is available on the web. Obviously one can disagree with their recommendation.

I WOULD LIKE TO KNOW AT WHICH LAB THE POSITIVE tTG OR EMA TEST WAS PERFORMED. FOR QUITE A LONG TIME ,I HAD NEVER RECEIVED A POSITIVE RESULT IN “SYMPTOMATIC ADULTS” (CRITERIA OF THE NIH CONCENSUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 2004).

THE HSITOLOGICAL CRITERIA (SO CALLED “GOLD STANDARD”) CANNOT R/O THE DIAGNOSIS IF ONLY ONE DUODENLA BIOPSY SAMPLE IS OBTAINED,AND A POSITIVE DIAGNOSIS IS ONLY MADE DEFINITE IF THERE IS CLINICAL AND HISTOLOGICAL RESPONSE TO THE DIET.

TO MY UNDERSTANDING,A POSITIVE HISTOLOGY IN THE PRESENCE OF ANY OF THE MULTIPLE POSSIBILITIES OF BEING “SYMPTOMATIC”,MAY JUSTIFY A DIETARY TRIAL HOWEVER THE DIAGNOSIS OF CELIAC DISEASE CAN STILL BE CHALLENGED WHEN RESULTS OF SEROLOGICAL AND HLA TESTS ARE CONTRADICTORY. THUS tTG AND EMA BECOME THE PRACTICAL SCREENING TOOL.

Comments are closed.