Peer Reviewed

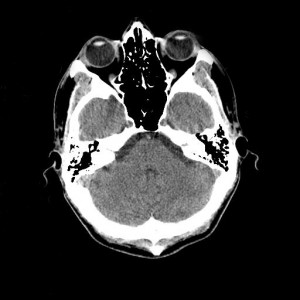

She was a thin, 4-year old girl brought to the Accident Centre by her mother for evaluation of new-onset bruising around the eyes after being an unseatbelted passenger in a motor vehicle crash three days earlier. She denied vomiting or having a headache, and her mother said that she had not been sleeping excessively or acting unusual. She was alert, ambulatory, and quiet but not in distress, without other injuries aside from bilateral periorbital ecchymoses not apparent at initial presentation three days before. Her “raccoon eyes” suggested cerebrospinal fluid leak from an anterior cranial fossa fracture that may have been occult at the time of initial presentation.[1,2] This supported the assessment that she had a closed basilar skull fracture, but was currently medically stable.[2,3] The patient’s mother was instructed to bring the child back to the Accident Centre if she displayed signs of worsening head injury or meningitis including becoming unusually drowsy, vomiting, becoming febrile or developing a headache[.4] The patient was sent home without further work-up.

The case took place not in New York, but at a large public teaching hospital in Accra, Ghana. This 2.3 million-person capital city in West Africa has a heavy burden of road accidents and traumatic injury. Prior to her discharge, her physician debated initiating further work-up including a non-contrast head computed tomography (NCHCT) scan. Definitive diagnosis of a skull fracture and evolving intracerebral bleed or swelling could initiate potentially life or neuron-saving intervention.

If the same scenario were to take place in the US to an American girl, we would follow standard protocols of care beginning the work-up with NCHCT and admitting the pediatric patient for monitoring.[3,4] If she developed signs of increased intracranial pressure or meningitis, neurosurgical intervention or antibiotics and critical care could be promptly initiated.[4] We are able to provide this high level of care in the US because emergency care is provided to all regardless of ability to pay, and in many states, hospital care for low-income children is adequately covered by state children’s health insurance.

Moreover, Medicare covers a majority of elderly American citizens, while younger Americans families are typically covered by employment-based private insurance. Therefore, US physicians and patients are often allowed to consider the cost of services secondary to biomedical necessity. However, if this child were in that segment of the US population without private or public insurance, or with low-quality private insurance, her family would be required to directly pay for the care provided after the fact, which can lead to financial hardship and bankruptcy.

There is a different reality for this girl in Ghana. Each patient’s financial resources directly impact the healthcare she receives. A majority of patients do not have private health insurance or means to pay out of pocket, and must quickly secure funds to pay for treatment of acute illness. There is a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) whose goal is to ensure access to basic healthcare services to all residents of Ghana.[5] However, this insurance covers only a limited basket of treatments and services, focusing on relatively lower-cost diagnostics and therapeutics.[6,7,8] Covered interventions include free maternal and obstetrical care, limited generic medications, general medical and surgical care, and outpatient clinic visits.[5,8] Services taken for granted in the US, such as cardiac surgery, elective orthopaedic and neurologic surgery, as well as hemodialysis, oncologic chemotherapy, and antiretroviral medication are not covered by NHIS.[5,7] The motivation for this scheme is based on the utilitarian rationale that with limited funds for healthcare, more years of healthy life could be saved by low-cost interventions provided to more people than high-cost therapies provided to fewer.

Even these cost-preserving measures are not sufficient to truly implement quality universal healthcare in Ghana, as the basic basket of NHIS reimbursement to providers and hospitals is both poor and unreliable, such that NHIS care is at times nearly charity work.[6,7] It is offered to all citizens, but only two thirds of the population is enrolled and private out-of-pocket payment still accounts for two thirds of total healthcare spending.6 Providers will often require their patients to directly pay for services even if the patient holds NHIS coverage or the patient will wait in large public clinics hampered by chronic capacity shortages.[6,7] There is not enough infrastructure or wealth distributed through the general population to offer the non-covered high-technology diagnostics and treatments to all without bankrupting the health system. If a patient lacks strong private insurance or wealth, clinical decision-making is based on both the medical needs and economic impact on the patient and the social network he/she relies upon.

The family of the Ghanaian girl with the head injury will need $250 Ghana Cedes (approximately $110 USD) for the head CT scan, as it is not covered by NHIS. Treatment initiated based on the scan could cost hundreds or thousands of Cedes. This patient’s family sells underwear and small tradable items in a market. They do not have private insurance or money in savings. A unique phenomenon developed out of necessity is pseudo-health insurance consisting of a vital social network of friends, family and tribe members who would pay for the scan. However, paying for expensive testing and care would place a financial strain on their network and the parents would eventually be expected to pay back as much as they could to those who lent money. If the social network is also poor, then the group is still limited in the healthcare they can afford. The physician was concerned that the family would forgo proper nutrition for this already thin child and her 3 siblings as they may divert their wages to paying back the borrowed money. Similarly, school fees may also be sacrificed such that the children would be kept out of school until the family finances normalized. By extension, the social network would also risk forgoing quality nutrition, basic healthcare, and school fees to pay for the CT scan up front. The decision to work-up and treat this possible closed head injury was complex beyond biomedicine. In order to preserve the well being of the group in the long run, short-term sacrifices and risks are taken. The physician determined that the child was stable enough that the adverse social effects of treating her outweighed potential medical benefits.

This complex decision-making strategy was repeated in varying forms throughout my time at the Korle Bu Hospital emergency center in Accra, Ghana. A patient with a near-total traumatic digital amputation could be referred to a specialized consultant hand surgeon for treatment. The cost would be ten times higher than that needed for repair by a 1st year Korle Bu general surgery resident. This particular injured patient was a very poor immigrant who did not have the money or social network to pay the private consultant fees. With this imposed financial reality, he accepted the affordable and less specialized immediate intervention, which was the only true option providing a chance of finger salvage.

Although Ghana has a near the full range of advanced life and limb saving medicine, from cardiac surgery to advanced MRI imaging to joint replacement, these modalities remain inaccessible to the majority of Ghanaians. Most simply cannot afford the out of pocket fees for this complex care. There is no sign that foreign aid is coming as Ghana’s panacea, so resource limitation for low-income segments of society is a reality. Decisions about the rational allocation of healthcare resources for Ghanaians always come with a trade-off: by paying for the 4-year old girl’s head CT, the family was sacrificing potential funds for food, education and basic needs for the child, the family, and the social network of extended family and tribe members who would assist in paying for the scan and treatment. Patients and healthcare providers in Ghana understand this concept of resource limitation, and place financial and social considerations at the forefront when negotiating diagnostic and care plans.

While healthcare decisions also come with a trade off in the US, they are often less directly visible. As US healthcare providers, we are not forced to consider the same immediate financial consequences of our medical decisions on most of our patients or the rest of the population. Health insurance in the US extends beyond our families into a far larger pool of members: aggregated pools of workers in private insurance plans or the tax-paying population supporting Medicare and Medicaid.

When an American physician and their patient covered by Medicare or private insurance choose high cost interventions that lack evidence-based survival benefit, i.e. aggressive, invasive, and intensive care medicine at the end of life, the decision does not reflect the true cost of the care. The US government provides an ever-increasing share of US healthcare, currently funding roughly one half of the 18% of gross domestic product spent on healthcare.[9] The growing US national debt is an indirect price of Medicare and Medicaid covered treatment.

US healthcare costs have increased faster than inflation over the past decade and we lead the world in healthcare spending per capita, despite having poorer metrics of health than peer nations.[9] While the reasons for this phenomenon are multifactorial, we might pursue medical approaches that empower patients and reduce costs in the health system. Recent evidence from the Institute of Medicine suggests that US patients choose less invasive, less costly diagnostic and treatment alternatives when presented with unbiased risks and benefits of each option.[9] Numerous randomized trials have demonstrated reduced therapeutic overuse when patient-centered shared decision-making is used in the doctor-patient relationship.[9,10]

The decision making for our Ghanaian girl was similarly focused on the patient’s and her family’s holistic well being, which included cost-consciousness. Each patient has a unique life history that influences his or her’s healthcare preferences, as illustrated by the Ghanaian cases presented here. In a sense, there was a choice between either paying for school fees or a head CT, with greater utility felt to be found in keeping the girl in school. Patient centered practice is a core competency, but is often de-emphasized in modern US medical practice as all parties are removed from the costs and implications of our care. I am reminded to place my patients’ perspectives and their priorities at the forefront while negotiating both the benefits and burdens of my services to them.

Dr. Steffen Haider is a 4th year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

Peer reviewed Antonella Surbone, MD, PhD FACP, Medical Ethics, Clinical Correlations

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

1. Herbella FA, Mudo M, Delmonti C, Braga FM, Del Grande JC. ‘Raccoon eyes’ (periorbital haematoma) as a sign of skull base fracture. Injury. 2001 Dec;32(10):745-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11754879

2. McPheeters RA, White S, Winter A. Raccoon eyes. West J Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;11(1):97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20411091

3. Sherif C, Di Ieva A, Gibson D, Pakrah-Bodingbauer B, Widhalm G, Krusche-Mandl I, Erdoes J, Gilloon B, Matula C. A management algorithm for cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with anterior skull base fractures: detailed clinical and radiological follow-up. Neurosurg Rev. 2012 Apr;35(2):227-37; discussion 237-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21947554

4. Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD Jr, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, Nadel FM, Monroe D, Stanley RM, Borgialli DA, Badawy MK, Schunk JE, Quayle KS, Mahajan P, Lichenstein R, Lillis KA, Tunik MG, Jacobs ES, Callahan JM, Gorelick MH, Glass TF, Lee LK, Bachman MC, Cooper A, Powell EC, Gerardi MJ, Melville KA, Muizelaar JP, Wisner DH, Zuspan SJ, Dean JM, Wootton-Gorges SL; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19758692

5. National Health Insurance Scheme. http://www.nhis.gov.gh 2013. Accessed November 24, 2013

6. Odeyemi IA, Nixon J. Assessing equity in health care through the national health insurance schemes of Nigeria and Ghana: a review-based comparative analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2013 Jan 22;12:9.

7. Blanchet NJ, Fink G, Osei-Akoto I. The effect of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme on health care utilisation. Ghana Med J. 2012 Jun;46(2):76-84.

8. Witter S, Garshong B, Ridde V. An exploratory study of the policy process and early implementation of the free NHIS coverage for pregnant women in Ghana. Int J Equity Health. 2013 Feb 27;12:16.

9. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine; Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21595114

10. O’Connor, A. M., H. A. Llewellyn-Thomas, and A. B. Flood. 2004. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: Shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Affairs( Millwood) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15471770

The author thanks Dr. Sari Soghoian for her conceptual guidance in the preparation of this manuscript

Commentary by Antonella Surbone MD PhD FACP, Clinical Correlations Ethics Editor.

The moving and insightful piece by Steffen Haider challenges us in many ways. His account of the thin 4 year old girl injured in Ghana and treated according to the local limited resources leads to a discussion of cost considerations and patient involvement in decision-making that applies to all countries, including Western ones and the US. Three issues are raised that have profound implications for ethical clinical practice: the importance of understanding and respecting cultural differences, the role of relational autonomy in medical decision-making, and the need to face cost containment not only at a societal level, but also with individual patients and their families.

Cultural differences have a deep impact on the way different people perceive health and illness, face suffering and dying. This is true for physicians and medical institutions as well as for patients. (1) Cultural competence is taught as a requirement for health care workers and institutions in the US and most western countries. (2,3) Communication varies in different cultures, and truth telling is not always culturally accepted. Yet a major evolution has occurred in the past two decades: most patients are now made aware of their diagnosis and information about prognosis or risks is increasingly being provided. (4) Patient autonomy and involvement in decision-making is consequently more respected worldwide.

The author portrays a poignant example of truth telling and involvement of the patient’s family in decision-making when he writes that “Prior to her discharge, her physician debated initiating further work-up including a non-contrast head computed tomography (NCHCT) scan. Definitive diagnosis of a skull fracture and evolving intra-cerebral bleed or swelling could initiate potentially life or neuron-saving intervention. … If a patient lacks strong private insurance or wealth, clinical decision-making is based on both the medical needs and economic impact on the patient and the social network he/she relies upon.” Clearly, this decision-making process is not based on autonomy as individual freedom, but rather as a matter of capability. According to Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen, freedom to achieve well-being is of primary moral importance, yet such freedom is to be understood in terms of people’s capabilities and real opportunities to do and be what they have reason to value (5).

This brings me to the second ethics issue that emerges from this piece: in contemporary philosophy and medicine, autonomy is no longer fathomed as a matter of abstract individual rights, but as a relational value based on internal and external circumstances including human and financial resources of the whole community (6,7). Accordingly, the locus of decision-making also shifts from the individual patient to a larger group. “If a patient lacks strong private insurance or wealth, clinical decision-making is based on both the medical needs and economic impact on the patient and the social network he/she relies upon…The physician was concerned that the family would forgo proper nutrition for this already thin child and her 3 siblings as they may divert their wages to paying back the borrowed money. Similarly, school fees may also be sacrificed such that the children would be kept out of school until the family finances normalized. By extension, the social network would also risk forgoing quality nutrition, basic healthcare, and school fees to pay for the CT scan up front. “

Family and community in Ghana constitute a vital social network. “A unique phenomenon developed out of necessity is pseudo-health insurance consisting of a vital social network of friends, family and tribe members who would pay for the scan. However, paying for expensive testing and care would place a financial strain on their network and the parents would eventually be expected to pay back as much as they could to those who lent money. If the social network is also poor, then the group is still limited in the healthcare they can afford.” By contrast, in most Western countries people find themselves alone deciding about their own health, or that of a relative, and tend to perceive their medical decision-making as a matter of individual choice, potentially affecting the rest of their lives, yet not of their community. When the whole community network, however, is involved in medical decision-making and members bear together the consequences and costs of it, taking those into account becomes a collective necessity. This is one of the reasons why it appears so difficult to address cost issues with western patients and their families.

But is it really so? Or we as physicians tend to solely act as gatekeepers of limited resources, without involving patients and families in understanding of cost issues and their extended repercussions? This is the third issue that this piece raises: is there an ethical way to address cost containment and to discuss it with individual patients? (8-10) The IOM report on Choosing Wisely shows that patients and families tend to opt for very reasonable options, according to their socioeconomic status as well as to their cultural values and individual priorities. (11) In my clinical activity as medical oncologist I have found that most patients and families comprehend the financial implications of their medical choices far deeper than we expect. The ethical quandary lies not in addressing cost issues, but in how we do it: if we are free of prejudices and truly respectful of our patients’ and families’ choices, while being open and honest about the cost of care, we have an ethical obligations to include what is now called the “financial toxicity” of most medical treatments (12,13). Discussing costs with our patients is appropriate and compassionate if the patient, family and physician act in concert to examine all aspects of decision-making, including all short and long-term medical and psychosocial perspectives of the illness and its treatments.

Health and money are incommensurable values: at the individual level balancing best care and its costs is almost impossible. Yet our life is about tough decisions and medicine is about our life: in western countries most of us may not have to face the impossible decision between optimal care or food and education for our children, but few of us have the luxury to ignore the financial implications of costly health care. Under different health care systems, people save money for medical care, fully aware not only of its potential direct and direct costs, but also of the intangible costs of caregiving. Being informed of the economic implications of treatments is a patient’s right. As Dr. Haider writes in his conclusion, in modern US medical practice all parties are removed from the costs and implications of our care. I am reminded to place my patients’ perspectives and their priorities at the forefront while negotiating both the benefits and burdens of my services to them.

Additional References:

1. Kagawa-Singer M, Valdez A, Yu MC and Surbone A. Cancer, culture and health disparities: time to chart a new course? CA: Cancer Clin J 2010; 60: 12-39.

2. Betancourt JR, Corbett J, Bondaryk MR. Addressing Disparities and Achieving Equity: Cultural Competence, Ethics, and Health-care Transformation. Chest 2014 ;145(1):143-8.

3. AAMC & ASPH. Cultural Competence Education for Students in Medicine and Public Health: Report of an Expert Panel, July 2012. Available at http://www.asph.org/document.cfm?page=836

4. Surbone A, Zwitter M, Rajer M, Stiefel R. (Eds) New challenges in communication with cancer patients. New York: Springer Verlag 2012.

5. Sen A, Nussbaum M. Capability and Well-being. in Nussbaum and Sen (eds.), The Quality of Life, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993, pp. 30–53.

6. Sherwin S. A relational approach to autonomy in health care. In Sherwin S, Coordinator, The Feminist Health Care Ethics Research Network, The Politics of Women’s’ Health: Exploring Agency and Autonomy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press 1998, pp. 19-44.

7. Surbone A. Telling Truth to Patients with Cancer: What is the Truth? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 944-950.

8. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA 2003; 290:953-58.

9. Sulmasy DP. Physicians, cost control, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 1992;116 :920-926.

10. Tilburt JC, Xynia MK, Montori VM et al. Shared decision-making as a cost-containment strategy: US physician reactions from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004027.

11. Institute of Medicine. IOM. Best Care at lower cost: The Path to Continuous learning health care in America. Washington DC: The National Academies Press 2013.

12. Moriates C, Soni K, Lai A, Ranji S. The value in the evidence: teaching residents to “choose wisely”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:308-10.

12. Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity – part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013; 2: 80-1, 149.

13. Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial Toxicity, Part II: How Can We Help With the Burden of Treatment-Related Costs? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013; 4:253-4, 256.

1

One comment on “School Fees Or Head CTs: Reflections For Ethical Clinical Practice”

sir,

I fully agree with both the author and editor.

Hats off to both of them for highlighting such a common problem seen in most developing and under-developed nations.

When millons of people are deprived of the advanced technology in radiology,we in cities and urban centres are misusing the technology for petty gains and minor ailments .The technology should reach every common man.It is hightime developed countries make efforts wholeheartedly to see that every human being is given the advantage of modern technology.Health for all should be the motto.

dr.balachandran

Comments are closed.