Please enjoy this post from the archives dated March 4, 2012

Please enjoy this post from the archives dated March 4, 2012

By Brian D. Clark

Faculty Peer Reviewed

The ability to critically assess the validity of a clinical trial is one of many important skills that a physician strives to develop. This skill helps guide clinical decision-making, and there are a number of things that we are trained to look for to help determine the validity of any given study. Right at the top of the list of factors that go into this appraisal is that of study design, with the randomized, placebo-controlled trial serving as the gold standard for testing new treatments. Drugs that are considered therapeutic failures are said to have “performed no better than placebo.”

As described in a recent article in The New Yorker, research into the basis of the placebo effect and its potential role in therapy is becoming more mainstream.[1] This year, the Program in Placebo Studies and the Therapeutic Encounter was created at Harvard, bringing together research into the placebo effect and its potential application in patient care. While the “realness” of the placebo effect has long been appreciated in shaping subjective responses such as pain, recent studies suggest that placebos may be useful in other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and emphasize the role of the patient-doctor interaction in shaping patient expectations.

An appreciation of the power of the placebo and the need to control for it in scientific studies followed the work of Colonel Henry Beecher. Beecher saw the effects of expectation and emotions in wounded World War II soldiers on their perception of pain. Published in 1955, his article “The Powerful Placebo” is widely cited; in it, Beecher concluded that the placebo effect is an important factor in almost any medical intervention.[2]

Following the discovery of endorphins, early evidence for a biological mechanism accounting for the placebo effect in analgesia came in a study published in 1978. Levine and colleagues wanted to determine if endorphins were responsible for patients reporting reduced pain after receiving a placebo. In the experiment, patients recovering from dental surgery were initially given morphine, the opioid antagonist naloxone, or a placebo and asked to rate their pain. The investigators focused on those who had initially received the placebo and then divided these patients into two groups based upon their response to placebo. Naloxone was then administered to the two groups, and the patients who had previously responded to the placebo experienced a significant increase in pain following administration of naloxone. Furthermore, naloxone had no effect in the patients who did not initially respond to the placebo.[3] Therefore, at least in the case of pain, placebos and patient expectation appear to have a very real effect on the body’s production of endogenous opiates in certain individuals.

To address the question of whether placebos could be useful as treatments outside the realm of clinical trials, a series of meta-analyses by Hróbjarsson and Gotzsche examined studies that randomized patients to either placebo or no treatment at all. After analyzing the results from over 100 such trials, the authors concluded that, in general, placebos had no significant effect on objective outcomes, but they had possible small benefits in subjective outcomes and for the treatment of pain.[4,5] As the authors pointed out, these meta-analyses do not provide justification for the therapeutic use of placebos outside the setting of clinical trials.

One argument against the routine use of placebos (such as sugar pills for improvement of subjective symptoms) is that by its very nature, a placebo is thought to require some element of concealment or deception. Previous work has shown a beneficial effect of placebos in patients with IBS.[6] To test whether concealment was necessary for this effect, Kaptchuk and colleagues randomized patients with IBS to either an “open-label placebo” treatment group or no treatment at all. The patients in the open-label placebo group were told that “the placebo pills were made of an inert substance, like sugar pills, that had been shown in clinical studies to produce significant improvement in IBS symptoms through mind-body self-healing processes.” They found that patients given the open-label placebo had significantly reduced symptom severity compared to the no-treatment group.[7] Thus, placebo-like treatment may be helpful in certain conditions such as IBS. This study suggests that the therapeutic effect is due the patients’ perception that the potential treatment, even if inert, has been shown to be helpful. This highlights the possibility that the patient-doctor relationship itself may be beneficial in certain conditions if the patient believes the doctor is trying to help him or her.

Commentary by Antonella Surbone, MD, PhD, FACP

Clinical Correlations Ethics Editor

This piece by Brian D. Clark on the placebo effect follows one that we posted in our Ethics section on February 18th 2009.[8] The present piece adds a different fresh perspective to a subject always relevant to clinical care. For further consideration and debate, I wish to point out to all readers the importance of the most interesting study by Kaptchuk and colleagues [7] that Brian reports in his conclusion. In my opinion and clinical experience, a good patient-doctor relationship, based on reciprocal honesty and trust, always has an inherent therapeutic value: this is why it so important to establish and maintain. I have added three references that readers may find interesting.[9,10,11]

Brian Clark is a 4th year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Dr. Antonella Surbone, MD, Ethics Editor, Clinical Correlations

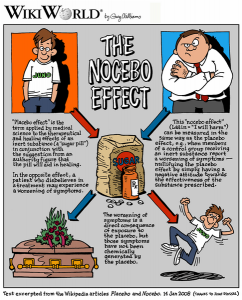

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References:

1. Specter M. The power of nothing. New Yorker. December 12, 2011:30-36. www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/12/12/111212fa_fact_specter

2. Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. JAMA. 1955;159(17):1602-1606. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13271123

3. Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet. 1978;2(8091):654-657. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/80579

4. Hróbjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1594-1602. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11372012

5. Hróbjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(1):CD003974. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20091554

6. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336(7651):999-1003. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18390493

7. Kaptchuk TJ, Friedlander E, Kelley JM, et al. Placebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PloS One. 2010;5(12):e15591. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21203519

8. Surbone A. Is prescribing placebos an ethical practice? www.clinicalcorrelations.org. February 18th 2009. https://www.clinicalcorrelations.org/?p=3399

9. Daugherty CK, Ratain MJ, Emanuel EJ, Farrell AT, Schilsky RL. Ethical, scientific, and regulatory perspectives regarding the use of placebos in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1371-1378.

10. Harris G. Half of doctors routinely prescribe placebos. New York Times. October 24th, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/24/health/24placebo.html

11. Berkowitz K, Sutton T, et al. Clinical use of placebo: an ethics analysis. National ethics teleconference. July 28, 2004. http://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/net/NET_Topic_20040728_Clinical_Use_of_Placebos.doc

One comment on “The Placebo Effect: Can Understanding Its Role Improve Patient Care?”

If placebo is sugar or any other sweet substance such as sodium saccharine, it produces endorphins, so in some studies this effect might have confounded the study. Instead, if capsules would have been given the reliability of theses studies would have been better.

Comments are closed.