Peer Reviewed

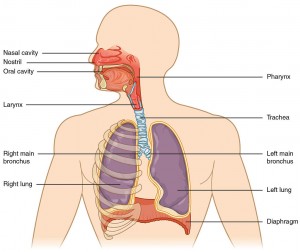

It was my first week on the wards as a third-year medical student, and I found myself huddled with the team in a busy corner of the Bellevue ED, listening to a man cough and wheeze his way through an interview. He was an elderly patient with an extensive smoking history–a lifetime of a destructive habit that had dilated and distorted his lungs beyond repair. He told us, between bouts of breathlessness, of worsening dyspnea and copious sputum production over the past couple of days, riding into his diseased alveoli on the viral coattails of a recent upper respiratory infection. Armed with a presumptive diagnosis of acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, we proceeded to manage his symptoms in full force, dilating his bronchioles and suppressing his inflammation. However, when it came time to administer supplemental oxygen, to give this man some much-needed breaths of air…we held back. I can distinctly remember my resident saying: “Make sure to titrate his oxygen to a sat between 88 and 92 percent.” At that moment, my resident was of course concerned about hyperoxic hypercarbia, a phenomenon that all of us are taught about in medical school, in which increasing oxygen saturation in a chronic carbon dioxide retainer can inadvertently lead to respiratory acidosis and death.1

But where do these magic numbers 88 and 92 really come from? What is the evidence against high-flow oxygen therapy in these patients? In one randomized comparison trial based in Australia, over 400 patients with probable acute COPD exacerbation were treated by paramedics with either oxygen titrated to a saturation between 88-92% or high-flow oxygen therapy, all while en route to the hospital. The authors found that all-cause pre-hospital or hospital mortality was significantly less in those patients who had received oxygen by conservative titration, with a relative risk reduction of 58%; these patients were also less likely to develop subsequent respiratory acidosis.2 Based on this study, there appears to be strong prospective mortality evidence in favor of withholding high-flow oxygen from COPD patients.

Why does the phenomenon of hyperoxic hypercarbia occur in the first place? Is there any evidence to back up the traditional “hypoxic drive theory”–a theory that is still taught in some medical school classrooms (as well as certain shelf examination preparation materials that shan’t be named)? Or has this historical explanation been debunked in favor of some other underlying mechanism? The earliest studies that warned against uncontrolled oxygen therapy in COPD date back to the 1940s; one investigator at the time theorized that hypoxia provided a vital “stimulus” to breathe in these patients, at the level of the sinoaortic nerves.3 And so, the theory of hypoxic drive was born. It postulates that chronic retainers bear a blunted response to carbon dioxide levels (and to their proxy, low serum pH), and that these patients therefore rely to some degree on hypoxemia in order to breathe.

Over the following years, the hypoxic drive theory gained traction within the medical community. It was not until the early 1980s that it was seriously called into question, at least within the scientific literature. In one prospective study at the time, COPD patients with acute respiratory symptoms each received 100% oxygen supplementation, which was found to decrease their minute ventilation by an average of nearly 20% (via a decrease in both tidal volume and respiratory rate). Surprisingly, this initial decrease in minute ventilation almost entirely reversed on its own within the next several minutes, even as these patients remained on 100% oxygen. The authors noted that despite this near-complete restoration of minute ventilation, arterial carbon dioxide tensions still remained significantly elevated compared to control, an observation that could not be explained by decreased minute ventilation alone.4 They hypothesized that the primary explanation for hypercarbia in the setting of oxygen supplementation was not alteration in minute ventilation, as had previously been thought, but rather, ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch. They reasoned that these patients were experiencing a loss of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, the physiologic process that in healthy people accompanies alveolar hypoxia and serves to redirect blood flow away from under-ventilated lung in order to optimize the V/Q ratio. This normal physiologic compensation, when overcome with excessive O2 administration, results in worsening V/Q ratios, that is to say, more areas in the lung where V/Q ratios are low and more areas of high V/Q. The extreme high V/Q areas that have no flow (no Q) represent dead space. In a situation where total minute ventilation remains constant, an increase in dead space diminishes CO2 excretion and results in higher PaCO2 values.

Almost two decades later, another study was published in which pulmonary vasculature modeling software was used to reinforce that same conclusion, namely, that increased oxygen levels contribute to hypercarbia chiefly by inhibiting hypoxic vasoconstriction and increasing alveolar dead space, and only secondarily by diminishing minute ventilation.5

Another mechanism that likely contributes to oxygen-induced hypercapnia in COPD is the well-studied Haldane effect, which was first proposed in 1914.6 The Haldane effect revolves around the hemoglobin-carbon dioxide dissociation curve, which shifts to the right with increased levels of oxygen, thereby increasing arterial carbon dioxide tension in the blood. This increase in PaCO2 is due to the fact that oxygenated hemoglobin binds to carbon dioxide relatively poorly compared to deoxygenated hemoglobin, and thus deposits more carbon dioxide in the bloodstream. By virtue of their tachypnea, patients with acute COPD exacerbation are not able to compensate and excrete this excess carbon dioxide through their lungs as effectively as they otherwise would in the absence of respiratory distress. Indeed, in the aforementioned study by Aubier and colleagues, the authors estimated that fully one quarter of the effect of oxygen on hypercarbia could be attributed to the Haldane effect alone.4

Regardless of the underlying mechanism (or most likely, mechanisms)… primum non nocere! Oxygen should never be withheld from a patient in situations of doubt–that much is certain. However, it is also important to recognize the prospective evidence against high flow oxygen in acute COPD exacerbation. And so, as I look back on my first week on the wards, huddled in the Bellevue ED next to the man with the broken lungs, I can proudly say that my resident did good. By holding back, and not over-zealously treating, he proved that he was up to date on the latest evidence regarding oxygen supplementation in COPD, and he may very well have spared this man a complicated and extended hospital course.

Jonathan Glatt is a 3rd year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Robert Smith, MD, Pulmonary, NYU Langone Medical Center

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

- Abdo WF, Heunks LM. Oxygen-induced hypercapnia in COPD: myths and facts. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):323-326. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23106947

- Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Effect of high flow oxygen on mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in prehospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5462. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20959284

- Donald K. Neurological effects of oxygen. Lancet. 1949;2:1056-1057.

- Aubier M, Murciano D, Milic-Emili J, et al. Effects of the administration of O2 on ventilation and blood gases in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122(5):747-754. http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/arrd.1980.122.5.747#.V-vuTU_ruDk

- Hanson CW 3rd, Marshall BE, Frasch HF, Marshall C. Causes of hypercarbia with oxygen therapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(1):23-28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8565533

- Christiansen J, Douglas CG, Haldane JS. The absorption and dissociation of carbon dioxide by human blood. J Physiol. 1914;48(4):244-271. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001659/full#footer-citing

2 comments on “Oxygen-Induced Hypercapnia in COPD: What is the Mechanism?”

1. Assuming the study is right, the deleterious effect of oxygen is not necessarily due to hypercapnia. It might be due to oxygen toxicity.

2. There is another benefit of titrated O2, especially if end-tidal CO2 monitoring is not being used. If the FiO2 is high, then O2 saturation will remain high as the CO2 rises. If the FiO2 is titrated to the minimum needed, and hypercarbia worsens, there will be immediate feedback to the clinician of a worsening situation because the O2 saturation will drop.

Very well written article! I was directed here from a comment on one of the articles on my website discussing the Hypoxic Drive Theory being debunked – https://bloggingforyournoggin.wordpress.com/2016/07/06/the-hypoxic-drive-debunked/

Similarly, my article discussed a V/Q mismatch secondary to hypoxic vasoconstriction and the Haldane effect in regards to the hypercapnia observed in COPD patients receiving oxygen. I have always been dubious of the 88 – 92% oxygen saturation range in the COPD cohort, despite continuing to manage these patients as such as this is the current recommendation.

The 2010 Austin et al. study compared titrated oxygen saturations of 88 – 92% in COPD patients to non-titrated high flow oxygen saturations of unknown percentage. One of the limitations noted was the lack of ABGs to record values such as PaO2, which could have been sitting in the high hundreds. Based on the literature search on 5 previous articles, there was a preconceived notion in this study that high flow oxygen in COPD patients is bad. What wasn’t mentioned is the fact that non-titrated high flow oxygen in ANY patient is bad.

For example, the recent AVOID study demonstrated a greater myocardial infarct size giving supplemental oxygen to a STEMI patient with normal oxygen saturations, compared to those titrated with oxygen to achieve normal oxygen saturations. The rationale for this is based on the oxygen free radicals that circulate in hyperoxic states promoting a deleterious inflammatory response, leading to secondary tissue damage. Could this same rationale not be applied in the COPD patient? There are numerous articles out there associating oxygen toxicity with various clinical consequences including diminished lung volumes, hypoxemia due to absorptive atelectasis, accentuation of hypercapnia, and damage to airways and pulmonary parenchyma.

Conclusions derived from research articles such as this inevitably result in clinicians shortening terms such as “non-titrated high flow oxygen” simply to “oxygen”. This then results in other clinicians arriving to a MET call with a patient having oxygen saturations of 70% with 2 L/min via nasal prongs because “the doctor said the patient is a CO2 retainer and not to give them too much oxygen”. I think we need to be careful in how people may interpret “holding back” oxygen therapy in a COPD patient, as this is often interpreted as withholding oxygen therapy instead of the intended meaning of not overzealously treating.

As clinicians that understand “not too much oxygen” means titrating it to achieve oxygen saturations of 88 – 92%, I believe it is really important to clarify this with nursing staff that are at the bedside 24/7 that may still be incorrectly associating this rationale with “knocking off the patient’s drive to breathe”. They are the ones that are going to be the difference between a couple more litres of oxygen or a decompensated, intubated patient.

I always make it clear to nursing staff that a patient will die from hypoxia much quicker than hypercapnia or oxygen toxicity. I generally want to make my hypoxic patient no longer hypoxic in the shortest space of time and would achieve this by turning the oxygen flow rate up. Once in the desired oxygen saturation range, I would wean the oxygen to the lowest flow rate to maintain that range…as I would with any other patient.

Comments are closed.