Peer Reviewed

Wedges are triangular tools that have traditionally been used to split wood along the grain. The mechanical advantage of a wedge is its ability to accomplish this split with less force and less waste of material. Its tapered end is snugly secured inside a small defect, and then a force is applied in order to separate a piece of wood neatly and precisely.

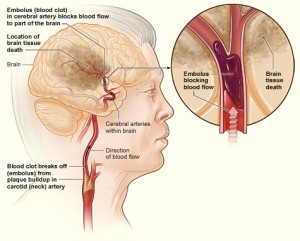

As a medical student at the Manhattan Veterans Affairs hospital, I witnessed this powerful tool wreak havoc in a two dimensional form. On the coldest day of the year, my resident received a call from the emergency department about a patient who was having symptoms consistent with a stroke. Before meeting him, I read the radiologist’s report of his head CT: “hypodense wedge in the left middle cerebral artery territory.”

* * *

Mr. S was much younger and healthier appearing than most of our VA patients, dressed in a plain white tee, khaki pants, and horn-rimmed glasses that reminded me fondly of my own blue-brown tortoiseshell pair. With salt-and-pepper hair and warm brown eyes, he looked like a kindly, middle-aged professor on a casual Sunday; I half-expected to see a folded New York Times and a mug of steaming tea at his bedside. We introduced ourselves as the medical team, and afterwards he pointed straight at me and said, “I like your glasses.” That would be the only coherent, complete sentence he would utter for the remainder of our interview.

Mr. S’s illness was not visible or palpable, but when we asked him what brought him to the hospital he was almost completely unable to produce words to describe what had happened to him. The image of the cheery professor shrank before my eyes. I saw that his warm brown eyes were full of fear and his glasses were broken, unnoticed by Mr. S in his moment of distress. His speech was halting and labored. Painful seconds lapsed between attempts at spoken phrases, during which Mr. S would turn his watering eyes away from us, shaking his head, frustrated by his inability to communicate.

We were grateful when Mr. S’s niece, who lives with him and had brought him to the hospital, appeared to tell the story. But as soon as Mr. S saw her he became agitated and irrationally fearful, shouting at her to leave and violently leaping out of bed to chase her out the door, saying it was too cold for her to stay. His niece tearfully told us that her uncle was not an ill-tempered man, and she couldn’t understand why he was so upset by her presence.

After she left, Mr. S’s aggressive exterior crumpled. He started crying and saying, “My wife…she’s so beautiful…she’s an angel.” Mr. S’s wife died three years ago of cancer. For the rest of the interview he continued to speak about her in disjointed phrases separated by tearful pauses, helplessly unable to answer our questions.

As I stood watching our patient, it struck me that I was living in a world in which I only knew one Mr. S – the Mr. S who could not speak a full sentence, who lashed out at his loving niece for being by his side, who cried in front of strangers about his dead wife, who spoke like a toddler, who presented to us as a disabled man.

But in this world there exists another Mr. S. As we discovered later, there is a Mr. S who runs a homeless shelter for men. He is an important and beloved figure in his community. He has touched so many lives with his energy and his commitment and his words.

There is a Mr. S who helped raise his brother’s daughter. In the morning he makes the coffee and she prepares breakfast, and so they begin their days together.

There is a Mr. S who took his wife to the hospital to get chemotherapy until she succumbed to her illness. Her abdomen was opened and her veins were bombarded with fruitless chemicals. There was nothing he could do except watch the cancer devour her. She was beautiful, he said. She was an angel, he said.

The only difference between now and then is a “hypodense wedge.” This previously healthy veteran with an unknown defect made contact with a wedge; it saw an opportunity to forge a separation between Mr. S’s mind and his ability to express what was on it. It made a clean cut, leaving Mr. S free of the more messy physical manifestations of illness that we are accustomed to seeing in the hospital, but depriving him of one of the most fundamental elements of his personhood: how he relates to his fellow human beings through speech.

Despite learning more about Mr. S throughout his hospital stay by talking with him and his family, it occurred to me that I would never really know him as he had been known by others in his life prior to that cold Sunday in February. A large part of understanding between human minds relies on the manner in which we communicate, and his ability to translate his thoughts into language was undeniably altered.

I could hardly believe that the abrupt occlusion of single artery could so swiftly create such a divide in a man’s life. A strategically placed wedge combined with an untimely force had made a split: between thought and expression of thought, between Mr. S before the stroke and Mr. S after the stroke. While this divide may heal with time, Mr. S will always carry the scar of ischemia, which first appeared to us, quite fittingly, as a hypodense wedge.

Kyra Edson is a 3rd year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Amar Parikh, MD, anesthesiology, NYU Langone Medical Center

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

One comment on “Wedge”

Thank you for this- clinical poetry..

Comments are closed.