Peer Reviewed

A middle-aged woman presents to the Emergency Department with 1 week of calf-pain and swelling. A venous duplex ultrasound reveals a non-compressible popliteal vein suggestive of deep venous thrombosis (DVT). After the diagnosis has been established, we run through our checklist of follow-up questions:

Have you undergone recent surgery? No.

Have you suffered recent trauma? No.

Have you taken any long plane or train rides, or have you been immobile for prolonged period of time? No.

Do you smoke cigarettes? No.

Do you take any estrogen-containing medications? No.

So, now what?

Establishing provoked versus unprovoked venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes DVT and pulmonary emboli (PE), was first described in the 19th century by the German pathologist, Rudolf Virchow. Virchow developed the eponymous triad describing the underlying etiology—hypercoagulability, venous stasis, and endothelial damage [1-3]. Today, VTE remains a common diagnosis, with an estimated incidence of 100 cases per 100,000 persons, annually, and this incidence increases significantly with age [1].

Once the diagnosis of VTE has been established, the next clinical question is whether the thrombus is “provoked,” meaning that a predisposing condition has been identified, versus “unprovoked” [3,4]. The most common causes of provoked VTE include surgery, trauma, prolonged immobilization, and malignancy, with other factors such as obesity, smoking, and increased circulating estrogens further compounding the risk [1,3-6]. One or more of these provoking conditions are identified in approximately 50 to 60% of diagnosed VTE [1], leaving nearly half of patients without a clear underlying etiology.

The clinical significance of distinguishing between provoked and unprovoked VTE is twofold. First, these entities are managed differently. Patients who are diagnosed with an unprovoked VTE require prolonged, if not indefinite, systemic anticoagulation, which comes with its own associated risks [4]. Furthermore, the therapeutic agent of choice differs based on the underlying cause, specifically when the VTE is associated with malignancy [7-10]. Second, and perhaps more importantly, provoked and unprovoked VTE differ in terms of risk of recurrence. In fact, 1 retrospective study demonstrated a nearly 50% lower recurrence rate when a clear provoking factor, particularly surgery in this study, had been implicated [4,6].

Due to these differences in both the management and risk of recurrence, distinguishing between provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolic events is key [6,7,9,10]. If no underlying cause is immediately apparent, as the case may be when VTE is associated with malignancy, a more thorough evaluation into potential precipitating factors is warranted. Given that a new diagnosis of VTE could serve as the presenting manifestation of an undiagnosed malignancy [3,11,12], the question arises: should we search for malignancy in all patients with a new diagnosis of VTE with the hope of potentially minimizing cancer-related morbidity and mortality [7,12]?

How extensively should we screen for underlying malignancy in patients with a new diagnosis of unprovoked venous thromboembolism?

To determine whether screening for malignancy in this population would be fruitful, we first need to understand how commonly cancer is found alongside a new unprovoked VTE. While older studies suggest that 10% of individuals with an unprovoked VTE are diagnosed with malignancy within 12 months of their VTE diagnosis, more recent data offers that the prevalence of cancer in this population may actually be closer to 4-5% [3,11,12]. Despite the lower prevalence, this figure represents a 4- to 6-fold increased risk of malignancy compared with the age-matched general population, suggesting that cancer is not an uncommon occurrence in this patient cohort [12,13].

Establishing effective malignancy screening strategies for patients with a new diagnosis of unprovoked VTE is an area of ongoing investigation [3,8]. Given that VTE may be associated with virtually any malignancy, the screening required to thoroughly evaluate for underlying cancer may be invasive, expensive, and time-consuming. furthermore, screening may also incur a significant psychological costs [3, 12,13].

To determine an appropriate screening strategy, a recent multicenter, open-label, randomized-controlled trial by Carrier et al compared limited malignancy screening alone (history, physical examination, basic laboratory testing, chest radiography, and age-appropriate cancer screening) to limited screening plus computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis in patients with a new diagnosis of unprovoked VTE. The primary outcome was the diagnosis of occult malignancy during a 1-year follow-up period. This study demonstrated that 33 of the 854 individuals (3.9%, 95% CI, 2.8-5.4) were diagnosed with a new malignancy during the 12-month follow-up period. Fourteen of 33 (3.2%, 95% CI 1.9-5.4) received limited screening, while the remaining 19 patients (4.5%, 95% CI 2.9-6.9) underwent screening with supplemental CT of the abdomen and pelvis (P=0.28). Thus, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of biopsy-proven malignancies identified in these 2 cohorts [3,11]. Another open-label, randomized-controlled trial by Robin et al compared a limited cancer screening strategy (physical exam, laboratory testing, and basic radiographs) to limited screening plus 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and low-dose CT [8]. As in the study performed by Carrier et al [3], this trial showed that more extensive screening did not lead to a significant difference in the rate of cancer-detection [8].

Though these studies did not detect a statistically significant difference in the diagnosis of occult malignancy with the addition of extensive imaging in this population, we must also consider the clinical implications this type of screening may have on patient outcomes. A systematic review from 2017 sought to determine whether screening for malignancy after an unprovoked VTE was effective at reducing the rates of both cancer- and VTE-related morbidity and mortality [7]. Four studies with 1,644 participants were evaluated, including both of the aforementioned randomized-controlled trials [3,8]. The primary endpoints were all-cause mortality, as well as VTE- and cancer-related mortality. Due to early termination in 2 of the studies, the authors of this Cochrane review concluded that there was insufficient data to establish whether this more extensive malignancy screening, and thus, the possibility of earlier cancer detection, provided any clinical benefit with regards to reducing cancer- or VTE-related morbidity and mortality [7]. Similarly, another meta-analysis of 10 studies found that, while more extensive cancer screening diagnosed more occult malignancies than a limited strategy, there was insufficient data to say whether this translated into improved morbidity and mortality in this population [12]. Further studies are warranted to determine whether a more extensive screening strategy yields improved patient outcomes over a longer follow-up period.

While asking if and how to screen these patients for malignancy, we must take into consideration that extensive cancer screening is not always “benign.” In the above trials, 15-24% of patients randomized to the extensive cancer screening group were subjected to additional, potentially invasive, testing to rule out malignancy [11]. This testing is associated with both significant economic and psychological costs for these patients [11-13]. These negative implications must be considered when developing an approach to screening.

So, what do we do with all of this data?

Despite the fact that a new unprovoked VTE may indicate an undiagnosed malignancy, studies have not demonstrated great success with extensive malignancy screening after the initial VTE diagnosis [3,7,8,11]. Based on the available data, it remains unclear whether extensive cancer screening results in clinically significant patient outcomes, such as reduced patient morbidity or improved survival, and whether there is a role for such screening in this population [7,13]. The 2017 International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidelines recommend screening for malignancy in patients with the first unprovoked VTE as follows [13]:

- Patients with unprovoked VTE shoulder undergo limited cancer screening, including a thorough medical history and physical examination, laboratory investigations (complete blood count, calcium, urinalysis, and liver function tests), and chest X-ray.

- Age- and gender-specific cancer screening (colon, breast, cervix, and prostate) should also be performed according to national recommendations.

So, with all that being said—how should we approach these patients?

As it stands now, we must maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for malignancy without subjecting patients to extensive and unnecessary testing. That is, the 4 words that we as clinicians fear most: use your clinical judgment.

Commentary by David Green, MD. PhD. Director Anticoagulation Lab NYU Langone Health Center

The association of malignancy and clotting events has been recognized for more than a century. Mechanistically, this can be understood by the fact that thrombin, the terminal enzyme of coagulation, is also a potent growth factor for tumor cells, and associated stromal and tumor cells express tissue factor which initiates coagulation. Thrombosis is a marker of more clinically aggressive cancers. Occasionally, clotting events may precede the clinical diagnosis of an occult malignancy. No study to date has shown a survival benefit for patients with VTE who undergo comprehensive cancer screening as compared to age appropriate cancer screening. The reason is straightforward: the subclinical occult malignancies that are detected are usually advanced/metastatic, and there is not likely to be a significant survival advantage to earlier detection and treatment of advanced neoplastic disease.

Dr. Allison Guttmann is an Associate Editor, Clinical Correlations and current Chief Resident for the internal medicine residency program at NYU Langone Health

Peer reviewed by David Green, MD. PhD. Director Anticoagulation Lab, NYU Langone Health

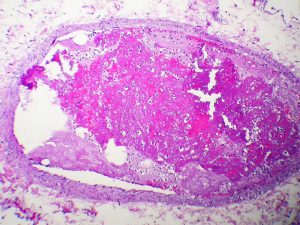

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

- Riva N, Donadini MP, Ageno W. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of venous thromboembolism: similarities with atherothrombosis and the role of inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(6):1176-1183. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25472800

- Stanifer JW. Virchow’s triad: Kussmaul, Quincke and von Recklinghausen. J Med Biogr. 2016;24(1):89-100.

- Carrier M, Lazo-Langner A, Shivakumar S, et al. Screening for occult cancer in unprovoked venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):697-704. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1506623

- Gupta A, Sarode R, Nagalla S. Thrombophilia testing in provoked venous thromboembolism: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1195-1196. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28586816

- Cheng YJ, Liu ZH, Yao FJ, et al. Current and former smoking and risk for venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001515.

- White RH, Murin S, Wun T, Danielsen B. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after surgery-provoked versus unprovoked thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):987-997. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20149075

- Robertson L, Yeoh SE, Stansby G, Agarwal R. Effect of testing for cancer on cancer- and venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related mortality and morbidity in people with unprovoked VTE. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD010837. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28832905

- Robin P, Le Roux PY, Planquette B, et al. Limited screening with versus without (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT for occult malignancy in unprovoked venous thromboembolism: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):193-199. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26672686

- Ross JA, Miller MM, Rojas Hernandez CM. Comparative effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) versus conventional anticoagulation for the treatment of cancer-related venous thromboembolism: A retrospective analysis. Thromb Res. 2017;150:86-89.

- van der Hulle T, den Exter PL, van den Hoven P, et al. Cohort study on the management of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism aimed at the safety of stopping anticoagulant therapy in patients cured of cancer. Chest. 2016;149(5):1245-1251.

- Khan F, Vaillancourt C, Carrier M. Should we screen extensively for cancer after unprovoked venous thrombosis? BMJ. 2017;356:j1081. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28330840

- van Es N, Le Gal G, Otten HM, et al. Screening for occult cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(6):410-417. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28828492

- Delluc A, Antic D, Lecumberri R, Ay C, Meyer G, Carrier M. Occult cancer screening in patients with venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(10):2076-2079. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28851126

3 comments on “How Far Should We Search for Malignancy in the Seemingly “Unprovoked” Venous Thromboembolism?”

How can we characterize this as being at once both “subclinical/occult” as well as “advanced metastatic?” Does it remain “subclinical and occult” until that sudden moment when it explodes throughout the body into an advanced major neoplastic metastatic manifestation? What about all those markers from Robbins that we memorized though rarely clinically monitoring?

I guess,screen most common malignancy as per risk factors and demographic factors …but I would like to look more for thrombophilia profile

What about occult, undiagnosed thrombophilia’s?. They presence could explained both, unprovoked and the “easier” development of provoked DVT-VTE. Would you agree with a “full” coagulation work up?.

Comments are closed.