Peer Reviewed

Let’s Start with a Case…

A 79-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation and stroke presents to the emergency department with new focal neurologic deficits in the setting of a recent upper respiratory tract infection. Notably, he reports it has been a while since he last took his Eliquis. Brain imaging reveals no acute findings but offers evidence of multiple chronic infarcts. These findings are characterized in future notes as a “history of cardioembolic infarcts attributed to nonadherence to anticoagulation therapy.” We asked him why he was “non-adherent” to Eliquis. His response: “It’s $600 a month.” To the medical student or trainee dutifully educated about the importance of anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation, yet often naïve to the complexities of insurance coverage, the case begs the question: Why are prescription medications so expensive? Aren’t they covered under Medicare? The answer is yes, although, unfortunately, coverage doesn’t guarantee affordability. From 2009 to 2018, Medicare enrollees spent an average of $2700 on prescription drugs per year.[1] Notably, during that same period, the average price of a prescription brand-name drug covered by Medicare Part D more than doubled.[2] According to a study by the Rand Corporation in 2018, US prices for brand-name originator drugs are three times higher than prices in comparable countries.[3] High prices also indirectly cost all taxpayers, as Medicare coverage of prescription drugs accounts for over $200 billion in federal spending.[4] Many experts believe that a major reason for these high prices is the fact that the federal government cannot negotiate pricing for drugs covered under Medicare with pharmaceutical companies.[5] Or rather, it couldn’t negotiate until now. Let’s take a step back a few decades to understand this historic change.

Medicare Part D

According to a study conducted in the United States in 2011, the vast majority (87.7%) of people aged 62 to 85 take at least one prescription medication, while at least one-third take five or more.[6] Yet, decades after its establishment in 1965, Medicare didn’t cover these outpatient medications, forcing people to pay out of pocket, often at enormous expense. In 2003, backed by a bipartisan consensus that something needed to change, President George W. Bush signed the Medicare Prescription Drug and Modernization Act into law, creating Medicare Part D. Briefly, Part D, which went into effect in 2006, is a voluntary option for people with Medicare to add coverage of outpatient medications that are self-administered at home, including drugs like apixaban (Eliquis) and atorvastatin (Lipitor). Part D coverage has two general options, each with slightly different eligibility requirements. Patients can either add a stand-alone plan (called Prescription Drug Plans or PDPs) or enroll in the comprehensive Medicare Advantage Plan, which falls under Medicare Part C and includes all other Medicare benefits.[7] Both options are provided by private companies via contracts with the federal government. As of 2023, over 50 million out of 65 million people with Medicare were enrolled in some form of Part D coverage.[8]

However, the legislation that created Part D included a provision known as the “non-interference clause,” which prohibits the federal government from negotiating with pharmaceutical companies or creating a price structure for reimbursement.[9],[10] Because Medicare represents a massive market share of prescription drug users and could thus wield immense leverage in negotiations as a single payer, it stands to reason that the clause helped to mollify pharmaceutical interest groups concerned about diminished profits and to ensure the legislation’s passage.

2023: Medicare Price Negotiations Begin

In August 2022, in the setting of rising inflation and increasing federal deficit, the Biden administration passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which, in addition to climate change initiatives, targeted Medicare Plan D, the first significant revision of the program in over a decade. Among other provisions, the legislation introduced a cap on the price of insulin paid by patients at $35 per month, a cap on out-of-pocket expenses at $2,000 a year, and a requirement that drug manufacturers pay rebates to the government should they raise prices for drugs covered under Plans D or B faster than the rate of inflation. As for the most controversial provision, the law also granted Medicare, or specifically the Secretary of Human Health and Services, the ability to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for pricing on certain prescription drugs covered by Medicare. The following ten initial medications were selected for negotiations:

| Brand | Generic | List price

(per month) |

Out-of-pocket cost to patient

(per month) |

| Eliquis | Apixaban | $561 | $55 |

| Jardiance | Empagliflozin | $570 | $0 to $50 or $169 |

| Xarelto | Rivaroxaban | $542 | $85 |

| Januvia | Sitagliptin | Not available | Not available |

| Farxiga | Dapagliflozin | $565 | $39 |

| Entresto | Sacubitril-Valsartan | Not available | Not available |

| Enbrel | Etanercept | $7,048 | $50 or $395 |

| Imbruvica | Ibrutinib | $13,000 | $0 to $45 |

| Stelara | Ustekinumab | $12,749 | Not available |

| Novolog | Insulin Aspart | Not available | Not available |

Medications with list price vs current average out-of-pocket cost to patient with Medicare Part D coverage for one month prescription. Source: Manufacturer Websites.

In future years, additional medications will be chosen for negotiations.[11] The selection process is quite detailed, and the chosen drugs must be responsible for large portions of Medicare spending, have been available for an extended period, and currently lack competition from other similar drugs.[12] In other words, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services picks brand-name medications that are expensive and have been around long enough for the manufacturer to have recouped expenses and made a profit but not long enough for a generic alternative to have been made to help bring down pricing. Negotiations for the first ten medications are to take place through 2024; new prices will come into effect in 2026.

Will Patients Benefit?

So, with all that said, will price negotiations make a difference? Will our patients actually pay less for their Eliquis and Jardiance? The simple answer is we don’t know. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the healthcare provisions in the law will save the federal government $283 billion over a decade, so in an indirect way, it is likely that there will be some cost savings for everyone.[13] That said, the price negotiation provision may not hold. Although all manufacturers of the first ten drugs selected for negotiation have agreed to come to the table, six of them, plus the US Chamber of Commerce and pharmaceutical trade groups, have also filed lawsuits challenging the provision on the grounds that it violates multiple constitutional amendments.[14] If the price negotiation program survives, critics argue it will effectively function as government price controls and discourage drug manufacturers from developing new drugs, particularly for conditions affecting older patients.[15]

Finally, returning our case, it turns out we buried the lead for illustrative purposes. Our patient is a former US Marine, eligible for care and prescription benefits through the Veterans Health Administration, which just so happens to have been one of a select number of federal agencies that is already negotiating prices with drug manufacturers. In fact, a report by the US Government Accountability Office determined that in 2017, the VA paid 49% less for brand-name prescription drugs than Medicare.[16] Our patient’s Eliquis is a Tier 3 copay drug at the VA, meaning he would be responsible for an $11 monthly copay, compared to the estimated $55 monthly copay with Medicare. Whether the VA model is applicable to Medicare warrants a deeper discussion that is at the crux of policy debates. As physicians, however, it is important to stay abreast of policy changes that have a significant impact on the cost of medications, so that we can consider the financial implications for our patients as we prescribe them.

Alison Cline is a Class of 2026 medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Reviewed by Michael Tanner, MD, Associate Editor, Clinical Correlations , Professor, Department of Medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

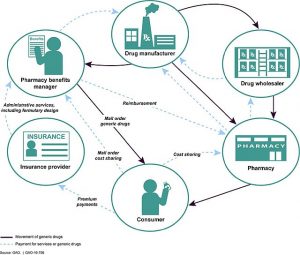

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons: This image is excerpted from a U.S. GAO report: www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-706

References

- Congressional Budget Office. Prescription drugs: Spending, use, and prices. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57772. Published January 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023

- Congressional Budget Office. Prescription drugs: Spending, use, and prices. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57772. Published January 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023

- Mulcahy, AW, Whaley, CM, Gizaw, M, Schwam D, Edenfield N, and Becerra-Ornelas AU. International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Current Empirical Estimates and Comparisons with Previous Studies. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 10 Prescription Drugs Accounted for $48 Billion in Medicare Part D Spending in 2021, or More Than One-Fifth of Part D Spending That Year. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/press-release/10-prescription-drugs-accounted-for-48-billion-in-medicare-part-d-spending-in-2021-or-more-than-one-fifth-of-part-d-spending-that-year/. Published July 12, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 10 Prescription Drugs Accounted for $48 Billion in Medicare Part D Spending in 2021, or More Than One-Fifth of Part D Spending That Year. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/press-release/10-prescription-drugs-accounted-for-48-billion-in-medicare-part-d-spending-in-2021-or-more-than-one-fifth-of-part-d-spending-that-year/. Published July 12, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, Gillet V, Alexander GC. Changes in Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication and Dietary Supplement Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med.2016;176(4):473–482. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8581

- Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-the-medicare-part-d-prescription-drug-benefit/ . Published October 17, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation website. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-the-medicare-part-d-prescription-drug-benefit/ . Published October 17, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, 117 Stat. 2066, 108th Congress (2003)

- Harvard Law Today. Can Medicare negotiate on popular drugs — or does a new law violate the Constitution? https://hls.harvard.edu/today/can-medicare-negotiate-on-popular-drugs-or-does-a-new-law-violate-the-constitution/. Published June 21, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- U.S. Department of Human Health and Services. HHS Selects First Drugs for Medicare Price Negotiation. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/08/29/hhs-selects-the-first-drugs-for-medicare-drug-price-negotiation.html. HHS Website. Published August 29, 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- Stolberg SG, Robbins R. U.S. Announces First Drugs Picked for Medicare Price Negotiations. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/29/us/politics/medicare-drug-pricing-negotiations.html. Published August 29, 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. CBO Scores IRA with $238 Billion of Deficit Reduction. https://www.crfb.org/blogs/cbo-scores-ira-238-billion-deficit-reduction. Published September 7, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2023.

- Stolberg SG, Robbins R. U.S. Announces First Drugs Picked for Medicare Price Negotiations. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/29/us/politics/medicare-drug-pricing-negotiations.html. Published August 29, 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- Stolberg SG, Robbins R. U.S. Announces First Drugs Picked for Medicare Price Negotiations. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/29/us/politics/medicare-drug-pricing-negotiations.html. Published August 29, 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Reports and Testimonies. Prescription Drugs: Department of Veterans Affairs Paid About Half as Much as Medicare Part D for Selected Drugs in 2017. U.S. Government Accountability Office website. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-111. Published December 15, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023.