Peer Reviewed

Once a death sentence, HIV/AIDS is now a treatable and preventable disease. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been a game-changer in HIV prevention since the FDA approved emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil (Truvada) in 2012 to prevent HIV transmission. While oral PrEP has significantly decreased infections, HIV transmission rates in the US remain concerning, with an estimated 31,800 new HIV diagnoses in 2022. New infections disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic populations, highlighting disparities in access to prevention and care.1

PrEP has proven to be highly effective in preventing HIV, with breakthrough infections being rare and often due to nonadherence or, in rare cases, viral mutations in patients who are adherent to their PrEP regimen.2 However, the daily pill form of PrEP can be challenging for patients to obtain consistently or remember to take. Adherence is crucial to effectiveness, and the risk of HIV transmission increases when patients do not take PrEP as prescribed. Several factors contribute to poor adherence, including patients’ perception of their own risk, younger age, and alcohol use.3

For most people, oral PrEP is well tolerated, with mild gastrointestinal side effects in the first month and a reduction in bone mineral density over time, although there is no increased fracture risk.3 Still, adherence remains a challenge. A meta-analysis showed that approximately 70% of individuals who started daily PrEP either discontinued or had suboptimal adherence within six months.4 This has prompted the development of alternative methods of PrEP delivery, including injectable PrEP.

In December 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable form of PrEP, cabotegravir (Apretude). An integrase inhibitor, cabotegravir is given as an intramuscular injection, with two loading doses four weeks apart followed by maintenance doses every eight weeks.5 In clinical trials, cabotegravir was found to be superior to Truvada in preventing HIV transmission.6 This is a crucial advance, especially for individuals who struggle with the daily pill regimen.

Patients with behavioral health challenges or those who wish to conceal their PrEP use to avoid stigma may find less frequent dosing with injectable PrEP to be beneficial.7 However, there are still barriers to its widespread uptake, including patients’ concerns about side effects, lack of awareness, and understandable distrust of the healthcare system among high-risk populations due to historical injustices. Transportation and time constraints can also prevent patients from attending regular clinic visits for injections.7 In addition to patient factors, healthcare providers need to be knowledgeable about injectable PrEP and to ensure that patients can receive their doses regularly.7

Cabotegravir was a pioneering first step, but an even longer-acting medication is on the horizon. In June 2024, Gilead released promising results from the PURPOSE 1 trial,8 which evaluated lenacapavir (Sunlenca), a capsid inhibitor that works at several stages of the viral replication cycle, for HIV prevention. Lenacapavir, injected only twice a year, was previously approved for treating multidrug-resistant HIV. In the PURPOSE 1 trial, lenacapavir injections every six months were compared to daily Truvada and emtricitabine/tenofovir (Descovy) in cisgender women and girls aged 16-25 in South Africa and Uganda. The results were striking: 100% efficacy in HIV prevention was achieved in the lenacapavir group, with no HIV infections reported among 2134 participants, compared to 16 cases among 1068 participants in the Truvada group and 39 cases among 2136 participants in the Descovy group.

While the adherence data for the Truvada and Descovy groups have yet to be released, it is likely that adherence played a significant role in the superior efficacy of lenacapavir compared to daily oral PrEP. These results are auspicious, although further studies are needed, particularly in cisgender men, transgender individuals, and nonbinary individuals who have sex with partners assigned male at birth. These populations are being evaluated in the ongoing PURPOSE 2 trial,9 with results expected in 2025.

Lenacapavir could dramatically reduce the burden of PrEP by requiring only two injections per year, making it easier to stay protected from HIV, especially in low-resource settings where access to daily medications can be inconsistent. However, like the eight-week injectable PrEP, there are still barriers to its adoption, including concerns about side effects, lack of provider and patient knowledge, and limited data in pregnant women.

The introduction of long-acting injectable PrEP, whether in the form of cabotegravir or lenacapavir, represents a significant step forward in HIV prevention. For patients who struggle with daily medication adherence, injectable PrEP is a more manageable option that can be tailored to fit their needs. However, it is important to address the challenges associated with its uptake and ensure that both patients and providers are educated about the benefits and logistics of injectable PrEP.

As more data emerge and lenacapavir becomes available, healthcare providers may consider transitioning patients using cabotegravir to lenacapavir, given the potential for fewer clinic visits and sustained HIV protection.7 With continued research and education, injectable PrEP could transform HIV prevention strategies, providing more people with the tools they need to stay HIV-free.

Allison Tu is a Class of 2027 medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Reviewed by Michael Tanner, MD, Executive Editor, Clinical Correlations

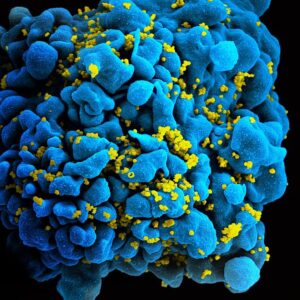

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, source: NIAID Creative CommonsAttribution 2.0 Generic license

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2018–2022. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2024;29(1). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed September 11, 2024.

- Ambrosioni J, Petit E, Liegeon G, Laguno M, Miró JM. Primary HIV-1 infection in users of pre-exposure prophylaxis. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(3). doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30271-X.

- Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, Sista N. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: where have we been and where are we going? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63 Suppl 2(0 2):S122-129. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f69.

- Zhang J, Li C, Xu J, et al. Discontinuation, suboptimal adherence, and reinitiation of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(4):e264-e268. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00030-3.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention. Published December 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention. Accessed September 12, 2024.

- Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):595-608. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101016.

- Miller AS, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. The potential of long-acting, injectable PrEP, and impediments to its uptake. J Urban Health. 2023;100(1):212-214. doi:10.1007/s11524-022-00711-w.

- Bekker LG, Das M, Karim QA, et al. 2024 Jul 24. Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir or Daily F/TAF for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Women. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2407001. Online ahead of print.

- Cespedes M, Das M, Hojilla JC, et al. Proactive strategies to optimize engagement of Black, Hispanic/Latinx, transgender, and nonbinary individuals in a trial of a novel agent for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PLoS One. 2022 Jun 3;17(6):e0267780. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267780. eCollection 2022.PMID: 35657826