Peer Reviewed

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. After all, it is far better to detect a serious illness before it develops its full harmful potential, or even prevent it from occurring at all, than to tackle the problem after the fact. When it comes to health prevention guidance, the recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) represent the standard of care.

The mission of the USPSTF is to “improve the health of all Americans by making evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services and health promotion.â€1 The first USPSTF was convened by the U.S. Public Health Service in 1984, concluding their work in 1989 with the publication of the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of 169 Interventions. A second Task Force was convened in 1990, leading to the second edition of the guide in 1996. In 1998, Congress gave authority to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to provide support to the Task Force through the 1998 Public Health Service Act. Since 2001, a rotating group of 16 volunteer experts have been nominated by the Secretary of Health and Human Services to serve four-year terms on the Task Force. Experts are chosen across various primary-care disciplines, including internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, behavioral health, obstetrics and gynecology, and nursing.2 These members meet three times a year, in March, July, and November, to discuss and vote on recommendations in the works.

So how does the Task Force make recommendations? First, a research plan is drafted, posted online for public comment, and finalized.3 After the research phase is complete, an evidence report is developed, and a recommendation statement is drafted. The USPSTF assesses factors such as the adequacy of evidence, the certainty of the evidence for net benefit of the preventive service, and the magnitude of the net benefit.4 These too are posted for public comment before they are finalized. The final recommendation statement must be ratified by the members of the Task Force and is then released for publication.

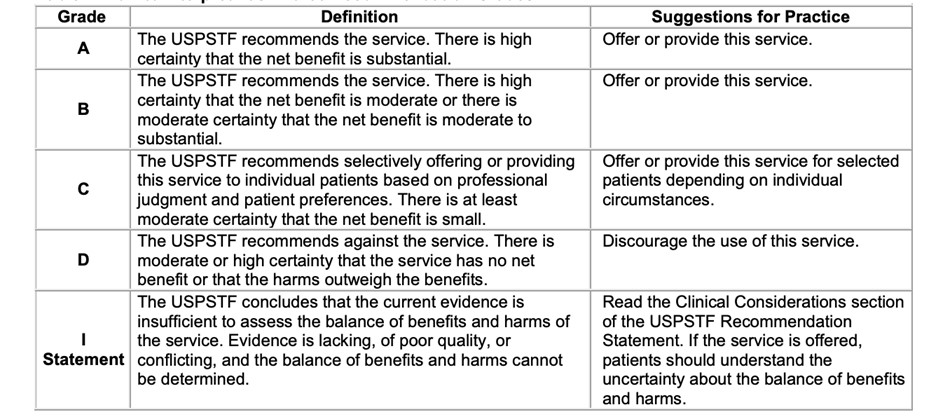

Letter grades are assigned to each recommendation statement that the USPSTF releases (Table 1). An “A†letter grade is a vote of confidence: there is high certainty that the benefit of the recommendation is substantial. A “B†grade is quite positive also: the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty of moderate-to-substantial benefit. A “C†grade indicates selectively offering the service to patients depending on individual circumstances. Actively discouraged services are given a grade of “Dâ€. An “I†grade indicates that there is currently insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. The Task Force does not consider the costs of a preventive service when determining a recommendation grade. Initially, the Task Force was purely advisory, although with the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicare was required to cover services with a USPSTF “A†or “B†rating, thereby connecting Task Force recommendations to coverage requirements for the first time.5

Table 1

While the USPSTF provides recommendations based on proven evidence of improved outcomes, subspecialty groups in the United States also provide their own recommendations, which are often more aggressive than those of the USPSTF. For example:

- American Cancer Society breast screening guidelines. The ACS recommends annual screening, and women should continue screening as long as they are in good health and are expected to live at least 10 more years, including over the age of 75.6

- American Urological Association (AUA) prostate cancer screening guidelines. While the USPSTF views prostate cancer screening as an individualized decision for men aged 55 to 69 and recommends against screening for men over 70, the AUA takes a more proactive stance, recommending screening for men at higher risk and at an earlier age, even as early as age 40.7

- American College of Cardiology (ACC) statin use guidelines. When it comes to statin use as primary prevention, both the USPSTF and the ACC use the PREVENT risk calculator, but the ACC recommends a broader use of statins for intermediate-risk individuals and older adults, including as low as 5% ten-year ASCVD risk.8

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Barrett’s esophagus (BE) screening guidelines. The ACG recommends a single screening endoscopy for patients with chronic GERD symptoms and 3 or more additional risk factors for BE, including male sex, age >50 years, white race, tobacco smoking, obesity, and family history of BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma in a first-degree relative.9

With such discrepancies between the USPSTF recommendations and subspecialty group guidelines, it is often up to the physician to interpret these guidelines and place them into practice.

The USPSTF is perhaps not well known to the general public, but at each primary care appointment, health maintenance practices are guided by recommendations from the USPSTF. After forty years tasked with minding the nation’s health, the USPSTF has proven itself essential in guiding preventive health.

Lydia Pan is a Class of 2026 medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Reviewed by Michael Tanner, MD, Executive Editor, Clinical Correlations

Image courtesy of https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/

References

- Siu A. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force procedure manual. December 2015. Accessed August 7, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/inline-files/procedure-manual2017_update.pdf.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Our members. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/current-members. Accessed August 7, 2024.

- Guirguis-Blake J, Calonge N, Miller T, et al. Current processes of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: refining evidence-based recommendation development. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):117-122. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00170

- Barry MJ, Wolff TA, Pbert L, et al. Putting Evidence into Practice: An Update on the US Preventive Services Task Force Methods for Developing Recommendations for Preventive Services. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(2):165-171. doi:10.1370/afm.2946

- Gluck AR, Gostin LO. Cost-Free Preventive Care Under the ACA Faces Legal Challenge. 2023;329(20):1733–1734. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.6584

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update from the American Cancer Society. 2015;314(15):1599–1614. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12783

- Wei JT, Barocas D, Carlsson S, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA/SUO guideline part I: prostate cancer screening. J Urol. 2023;210(1):46-53.

- American College of Cardiology & American Heart Association. 2018 AHA/ACC cholesterol treatment guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(24):2935-2957. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680