Peer Reviewed

Evolutionary theory, much like medical practice, is governed by tradeoffs. In an ideal world, an environmental challenge would be met with a corresponding adaptation perfectly suited to the task, without caveat; but the natural world is not ideal, and there is always a catch. Medicine is likewise a balancing act. The ideal treatment is one without risk, and wholly effective against its target, benevolent in its effects; the ideal disease would be straightforwardly malignant, readily identified, and responsive to medical intervention. In practice, the lines are blurred: treatments can confer disease, and what causes disease may have benefit.

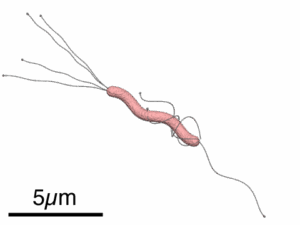

H pylori is one of a handful of ancient infectious organisms, a class that includes Mycobacterium tuberculosis, intestinal helminths, and filarial nematodes. It possesses highly specialized adaptations that allow it to thrive in a unique ecological niche: the bactericidal conditions of the human stomach (pH 1.5-3.5). These include the synthesis of acid-neutralizing urease; multiple flagellae to enable motility through thick gastric mucous to the epithelium below; and specialized proteins to anchor it, inflicting inflammatory damage to extract nutrients from epithelial cells while averting a destructive immune response.1,2 Colonization is typically established in childhood and maintained as a chronic infection into adulthood, with an estimated 80% of carriers remaining asymptomatic despite gastric immune cell infiltration and carcinogenic inflammation.3

This bacterium accompanied humanity in our migration out of Africa 60,000 years ago, with increasing evidence of H pylori colonization extending back at least 100,000 years–approximately one-third of our tenure as a species.4 Today, its global prevalence has been estimated at an impressive 43.9%, which represents a decrease from over half of the global population (52.6%) prior to 1990. The reasons for the decrease are multifold, attributed to general improvements in hygiene and sanitation associated with increasing socioeconomic status, as well as dedicated public health initiatives for eradication.5

With regard to the latter, H pylori owes the honor to its bad reputation as a well-demonstrated cause of gastric disease and mortality, giving rise to gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric lymphomas and gastric adenocarcinomas.2 Gastric malignancy represents a significant cause of mortality as the fifth most common cancer globally, having the third highest mortality rate. H pylori alone has been implicated in up to 75% of non-cardia gastric cancers, and up to 98% of those in the cardia.6 A meta-analysis of cohort studies estimated that individuals with H pylori are roughly six times more likely to develop gastric cancers (non-cardia), compared to those without.7 Complications of H pylori infection are not limited to the stomach. It has also been implicated in iron and vitamin B12 deficiency, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and childhood growth deficit, with their associated sequelae.1 Though an old associate of humanity, H pylori is far from an “old friend” and contributes considerably to global health burden.

Nonetheless, a curious consequence of natural selection is that organisms adapted to harsh conditions (infectious or otherwise) may in due time become somewhat reliant on those conditions, experiencing adverse consequences with their removal. The “disappearing microbiota” theory speculates that modern loss of ancestral bacterial diversity by various causes (iatrogenic, sanitation, decreased vertical transmission) predisposes to chronic disease through dysregulated immune development.8 Humanity has been host to H pylori since prehistory, and with relative ubiquity; evolutionarily speaking, H pylori presence in the microbiota is “standard,” and its recent decline is the aberration (one of many in our rapidly-shifting modern environment). On this basis, its absence has been suggested to have pathologic effects.

One consequence of interest is the association between H pylori eradication and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Inverse associations have been previously demonstrated between H pylori prevalence and the incidence and severity of GERD, which (like H pylori-associated gastritis) has its own serious sequelae, including esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma.1,9 These associations remain controversial, contested by other studies demonstrating benefit of H pylori eradication for GERD symptoms, although likely dependent on the type of gastritis under investigation. Protective effects of H pylori have been best demonstrated in populations with corpus-predominant or atrophic gastritis, as seen in Chinese cohorts in the form of significantly reduced severity and prevalence of GERD and its sequalae, with mixed or conflicting results in antrum-predominant cohorts (as in the US).9,10 These protective effects may be a result of hypochlorhydria induced by H pylori infection of the gastric epithelium, causing atrophy and impairment of acid production. Eradication of H pylori and restoration of acid-producing capabilities would thus raise the acidity of the refluxate. By this mechanism, in combination with other physiological changes of modernity–reduced esophageal peristalsis, lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction, increasing weight, and greater hiatal hernia incidence–H pylori eradication efforts may have an unintended tradeoff of worsening GERD.1,10

The stomach is also an endocrine organ, with the gastric corpus releasing two-thirds of the body’s supply of ghrelin, a hormone responsible for stimulating appetite. In much the same manner as acid production, H pylori infection has been proposed to reduce ghrelin production by damaging ghrelin-producing cells in the gastric epithelium, suppressing appetite and weight gain. This may be the mechanism by which H pylori infection in childhood induces growth delay, and by which adult H pylori carriers exhibit comparatively reduced body-mass index.1,10 In turn, H pylori eradication has been demonstrated to increase ghrelin levels.1 This decreased appetite suppression, taken together with concurrent decline in H pylori prevalence in Western countries, has been theorized to play a role in rising obesity and metabolic sequelae.

H pylori eradication has been implicated in yet another shift in modern medicine: the rise of atopic and inflammatory pathology. In accordance with the “hygiene hypothesis,” which theorizes that infectious exposures during early childhood are crucial for the development of immune tolerance and prevention of hyperreactivity, H pylori’s historical ubiquity in the human microbiome and early colonization in childhood may suggest a role in immune desensitization. Supporting this, inverse associations have been demonstrated between H pylori infection and asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis, although further investigation may be necessary to differentiate the effect of H pylori from co-infections also associated with less hygienic conditions.2,11 Similar negative associations exist for inflammatory bowel disease, which has also exhibited increasing prevalence with improvements in socioeconomic status and sanitary standards. This may be explained by H pylori’s long coevolution with host immune defenses: its success as a chronic infection may lie in its ability to upregulate production of regulatory T cells in gastric mucosa. The resulting anti-inflammatory effects are both immediate, reducing local inflammation to permit bacterial survival, and systemic, increasing levels of circulating regulatory T cells with immunosuppressive activity.1,12 Vanishing exposure to H pylori and similar infections in early childhood, though beneficial in prevention of their significant long-term complications and mortality, may yet contribute to loss of immunosuppressive mechanisms and give rise to diseases of immune dysregulation.

This is not to imply that H pylori is benign, nor to discourage screening, treatment, or public health campaigns of eradication. Chronic infection remains a significant contributor to global mortality and gastric malignancy. Nonetheless, it is always important to consider the full ramifications of any intervention, in public health or individual patients. One cannot assume that there exists treatment without tradeoff, whether from an evolutionary or a medical standpoint, and it is better to be informed as to the nature of that tradeoff than to assume a straightforward relationship between disease and cure.

H pylori has been adapting in tandem with human physiology for millennia; it has been shaped by the harsh selective pressures of our anatomy into a uniquely specialized organism. Is it unreasonable to wonder if we have not, in turn, been shaped by it?

Lauren Maytin is a Class of 2027 medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Reviewed by Michael Tanner, MD Executive Editor, Clinical Correlations

Image Courtesy of Y tambe, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

References

- Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(9):2475-2487. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/38605

- Jessurun J. Helicobacter pylori: an evolutionary perspective. Histopathology. 2021;78(1):39-47. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/his.14245

- Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):19. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-023-00431-8

- Correa P, Piazuelo MB. Evolutionary history of the Helicobacter pylori genome: implications for gastric carcinogenesis. Gut Liver. 2012;6(1):21-28. https://www.gutnliver.org/journal/view.html?volume=6&number=1&spage=21&year=2012

- Chen YC, Malfertheiner P, Yu HT, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and incidence of gastric cancer between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology. 2024;166(4):605-619. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016508523056871?via%3Dihub

- Shirani M, Pakzad R, Haddadi MH, et al. The global prevalence of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):543. https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-023-08504-5

- Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49(3):347-353. https://gut.bmj.com/content/49/3/347

- Blaser MJ. The theory of disappearing microbiota and the epidemics of chronic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(8):461-463. https://www.nature.com/articles/nri.2017.77

- Wu JC, Sung JJ, Chan FK, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with milder gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(4):427-432. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00714.x

- Zhao T, Liu F, Li Y. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on esophageal motility, esophageal acid exposure, and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1082620. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1082620/full

- Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Heliobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):821-827. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/412291

- Bagheri N, Azadegan-Dehkordi F, Rahimian G, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Shirzad H. Role of regulatory T-cells in different clinical expressions of Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Med Res. 2016;47(4):245-254. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0188440916301059?via%3Dihub