Faculty Peer Reviewed

A healthy 40-year-old woman comes into your office for a routine health exam. After you have performed a clinical breast exam, she asks you whether she should be examining her breasts on her own at home…

Breast self-exam (BSE) seems sensible. Empowering a patient to develop a sense of a personal norm could allow for easier recognition of breast changes, and could perhaps lead to earlier evaluation by a medical professional. There is a great deal of controversy, however, about the recommendation of this practice to patients. Few studies have looked at the efficacy of BSE, and therefore the risks and benefits remain somewhat unclear. Patients and physicians are faced with ambiguous or even disparate guidelines, including those from the American Cancer Society that suggest counseling women about the risks and benefits of BSE,[1] or from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that recommend that women have “breast awareness,†but recommend against routine instruction in BSE.[2]

The literature suggests that technique and level of skill may be important variables to consider when evaluating BSE. A case-control study by Newcomb and colleagues determined that the performance of more thorough breast self-exams resulted in a 35% decrease in the occurrence of late-stage breast cancer when compared with women who did not perform breast self-exams, independent of exam frequency. Thoroughness of the exams was evaluated by self-reported description of recommended BSE techniques, and, although a small number of women met criteria for a thorough exam, this was by no means the norm. Ultimately, the authors concluded that, despite the decrease in late-stage breast cancer as a result of a more thorough exam, because the majority of the women in the study reported a lack of self-proficiency in BSE, the typical performance of BSE provides no benefit.[3] The importance of a thorough exam is further supported by a study by Harvey and colleagues that stresses the importance of three components of the BSE: visual inspection of the breast, palpation with the finger pads, and examination with the three middle fingers. When compared with women who performed all three of the components in regular breast self-exams, women who omitted one or more of these components had an increased chance of death due to breast cancer or distant metastases (OR=2.20, 95% CI 1.30-3.71, p=0.003), even after adjustment for confounding variables.[4] Based on these data, it seems possible that patient education regarding the necessary components of a thorough BSE could produce a potential benefit, even though with typical practice of BSE no benefit was seen; however, a meta-analysis of trials involving BSE instruction failed to identify lower mortality in the BSE group (pooled RR=1.01, 95% CI 0.92-1.12).[4] The benefit of a thorough exam shown by the Newcomb and Harvey studies likely represents only a theoretical benefit without supportive data in practice.

A 2003 Cochrane Database meta-analysis examined the only two randomized clinical trials that have studied BSE versus no intervention in an attempt to determine whether screening for breast cancer by BSE reduces mortality.[8,9] Ultimately, the systematic review found no statistically significant difference in breast cancer mortality with BSE when compared with the control group (RR=1.05, 95% CI 0.90-1.24), but close to twice as many biopsies with subsequent benign results were performed in the BSE group (RR=1.89, 95% CI 1.79-2.00). This review indicates that the performance of breast self-exams represents a potential harm with no concomitant benefit,[5] a conclusion that is further supported by two additional meta-analyses that examined both observational and case control trials in addition to the randomized clinical trials.[6],[7] Of note, while both randomized clinical trials reported increased identification of benign tumors in the BSE group, the Russian study by Semiglazov and colleagues also found that increased numbers of malignant tumors were identified in the BSE group (RR=1.24, 95% CI 1.09-1.41),[8] a finding not supported by the study of women in Shanghai by Thomas and colleagues (RR=0.97, 95% CI 0.88-1.06).[9] Although the results of the Russian study show that BSE may promote identification of malignant tumors, both studies found no significant difference in tumor size or stage at diagnosis in the malignancies identified when comparing control versus BSE groups,[8,9] implying that increased identification is not synonymous with earlier identification. The failure of BSE to confer a mortality benefit can seemingly be explained by the lack of earlier identification of malignancy with this technique. Furthermore, both studies included intensive instruction in BSE, and their failure to show decreased mortality with BSE confirms that the benefit of a thorough exam proposed by the Newcomb and Harvey studies is only theoretical and does not have evidentiary support in these subsequent studies.

Based on the data available at this moment, several groups have reached very different conclusions. After evaluating BSE through a systematic review of the literature and the use of population modeling techniques, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against the practice of physicians teaching patients how to perform a BSE (grade D recommendation). [10] The USPSTF recommendation is in direct opposition to recommendations offered by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which recommends BSE, despite the lack of definitive data to support or refute the recommendation, because the practice of BSE has the potential to identify palpable breast cancer.[11] Despite the lack of concrete evidence, studies show that a majority of primary care providers polled feel that BSE is “somewhat effective†and a majority also recommend BSE to their patients aged 40 and older, but only a minority classify this examination as “very effective.â€[12] Ultimately, disparate guidelines are present, but based on the accumulated data regarding the efficacy of BSE, the evidence does not support physicians recommending BSE or teaching their patients the techniques required to perform it. Studies have failed to show a mortality benefit with BSE and instead have shown a potential harm, with increased biopsy rates of benign tissue in the BSE groups. While study findings indicate that intensive instruction in BSE does not decrease mortality, the potential benefit associated with certain components of BSE technique remains largely unaddressed, and represents a possible focus of future studies.

Katherine Husk is a 4th year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

Peer reviewed by Nate Link, MD, NYU Langone Medical Center

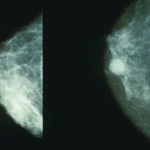

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References

[1]. Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003:53(3):141-169.

[2]. Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009:7(10):1060-1096.

[3]. Newcomb PA, Weiss NS, Storer BE, Scholes D, Young BE, Voight LF. Breast self-examination in relation to the occurrence of advanced breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991:83(4):260-265.

[4]. Harvey BJ, Miller AB, Baines CJ, Corey PN. Effect of breast self-examination techniques on the risk of death from breast cancer. CMAJ. 1997:157(9):1205-1212.

[5]. Kösters JP, Gøtzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:(2):CD003373. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12804462

[6]. Hackshaw AK, Paul EA. Breast self-examination and death from breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003:88(7):1047-1053.

[7]. Baxter N; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Preventive health care, 2001 update: should women be routinely taught breast self-examination to screen for breast cancer? CMAJ. 2001:164(13):1837-1846.

[8]. Semiglazov VF, Manikhas AG, Moiseenko VM, et al. Results of a prospective randomized investigation [Russia (St.Petersburg)/WHO] to evaluate the significance of self-examination for the early detection of breast cancer. Vopr Onkol. 2003:49(4):434-441.

[9]. Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002:94(19):1445-1457. http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/94/19/1445.full

[10]. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009:151(10):716-726, W-236. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf09/breastcancer/brcanrs.pdf

[11]. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 452: Primary and preventive care: periodic assessments. Obstet Gynecol. 2009:114(6):1444-1451.

[12]. Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Han PK, Benard VB, Breen N. Breast cancer screening beliefs, recommendations and practices: Primary care physicians in the United States. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3101-3111. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21246531

One comment on “Breast Self-Examination: Worth the Effort?”

Comments are closed.