Peer ReviewedÂ

Last December, an unremitting sore throat led President Barack Obama to see an ENT. When the fiberoptic exam revealed soft tissue swelling in his throat, his physicians ordered a CAT scan. After a 28-minute visit to Walter Reed Hospital and a normal imaging study, he was diagnosed with acid reflux.  It is likely that the president’s doctors were acting in an overabundance of caution. Unfortunately, President Obama is not the first American president to get superfluous medical care. For Obama, an unnecessary CAT scan was likely harmless, but for one of his predecessors, James A. Garfield, medical overreach turned out to be deadly.Â

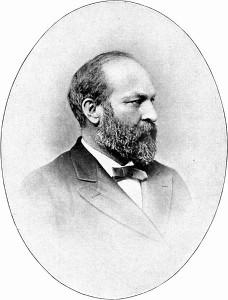

Unlike more popular and longer-tenured presidents, many are unfamiliar with the details of Garfield’s life. As reviewed in Candice Millard’s book, “Destiny of a Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President,†Garfield was born in squalor in rural Ohio and by age 26 had worked his way up from janitor to President of Williams College. He was a Union General in the Civil War, winning the key battle of Middle Creek, which kept Lincoln’s home state Kentucky in the Union. He was an eight-term congressman and senator. At the 1880 Republican National Convention, he was nominated for President, mostly against his own wishes. He only served in office for 200 days (the 2nd shortest presidential term behind William Henry Harrison’s 31 days).

On July 2, 1881, the President rushed to catch a train at Sixth Street Station in Washington D.C. There, his assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, shot him on the right side of his back. Guiteau was an unbalanced individual who believed that God had commanded him to assassinate the President. In his out of touch reality, Guiteau believed this action would allow him to become Ambassador to France. Guiteau was eventually tried, convicted, and hanged for murder. However, during the trial, part of Guiteau’s defense was that the true murderers of President Garfield were actually his doctors.  Oddly enough, as Millard careful analyzes, there may be some truth behind his statement.

Back at the train station, Garfield’s condition was bleak. The bullet entered his back, four inches to the right of his spinal column, damaging a lumbar vertebra and several ribs before lodging itself behind the pancreas. It did not damage any vital organs, nor did it hit the spinal cord. Some have argued that he likely would have survived if just left alone. Unfortunately at the time of the shooting, there was no way to determine the location or trajectory of the bullet.

On the floor of the train station, no less than 10 doctors invasively examined the president; the most infamous was the aptly named Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (his given name was Doctor). Robert Todd Lincoln, Secretary of War and son of Abraham Lincoln, called on Dr. Bliss after the shooting. Lincoln had always been impressed with the care Dr. Bliss had provided to his father after his assassination at Ford’s Theater.

Unfortunately Dr. Bliss’s medical practices were out of date and at times fraudulent. He was once thrown in prison for accepting bribes. Additionally, he forayed into medical quackery with his miracle substance cundurango, which he marketed as “The wonderful remedy for cancer, syphilis, scrofula, ulcers, salt rebum and other chronic blood diseases.†“Destiny of the Republic†scrutinizes Bliss’s rejection of antisepsis. Even though most European physicians adopted Joseph Lister’s theories and methods on antisepsis, American physicians remained dogmatic in their attitudes against cleanliness. Bliss surrounded himself with physicians who also did not buy in to Lister’s hypotheses. One of these physicians was Frank Hamilton, a surgeon at Bellevue Medical College. Hamilton preferred using warm water on surgical wounds to prevent infection.

After several physicians had done manual exams of the president’s wound (using unwashed hands), Bliss placed 2 unsterilized probes inside of the bullet wound in an attempt to determine the trajectory. Convinced that the bullet was near the liver (based on his blind, unsterilized exam), Bliss’s medical care for the next 80 days mostly revolved around attempting to locate the bullet. However, he was hampered by his own arrogance. While using a modified metal detector developed by Alexander Graham Bell, he only allowed the inventor of the telephone to investigate the president’s right side, near the liver. Had he allowed examination of the president’s left side, he likely would have found the bullet. This tool went on to serve a unique purpose as an imaging modality before access to the x-ray was widely available.

At the White House, Bliss and his medical staff performed several procedures to lance abscesses and place drainage tubes (while not using clean instruments). As the President’s condition worsened over the next 11 weeks, Bliss refused to admit that the president was septic and dying, saying several weeks into his medical care “Not the minutest symptom of pyemia has appeared thus far in the President’s Case. The wound is healthier and healing rapidly.†Meanwhile, “septic acne,†or pus-filled abscesses, formed all over Garfield’s body, including his arms, back, and even his parotid gland (which burst and drained into the President’s middle ear). Bliss and his men continued to place drainage tubes and lance abscesses. Later, at autopsy, a long sinus tract with multiple abscesses was found going toward the liver (with no bullet nearby).

More than the president’s overwhelming sepsis, Bliss was concerned with his extreme 80lb weight loss (from 210 to 130 pounds). To counteract the president’s cachexia, Bliss prescribed rectal feeding, reminiscent of CIA torture practices. In the rectal feeds, Bliss included beef bouillon (predigested with hydrochloric acid), warmed milk, egg yolks, and opium every 4 hours for 8 days. He also used varying mixtures of whiskey and charcoal in his feeds.

While James Garfield’s presidency and assassination are now only footnotes of American history, his plight was certainly a tragedy that potentially could have been avoided. Candice Millard’s book not only tackles the topic with attention to medical details, but it is also readable and enjoyable. She suggests that had Bliss and his counterparts bought in to Joseph Lister’s methods (as Europeans had already done and American physicians would do in about 15 years), the president’s life may have been saved. Additionally, her conclusion is that Bliss’s obstinance in refusing to recognize Garfield’s septic shock likely prolonged the President’s suffering. Today, we should use this story as a lesson: sometimes less medical intervention and care is better — even for a President. Every potential invasive test has a consequence, and we must always weigh its risks and benefits. It is imperative that we stay up to date with current research and medical practices and not become set in our traditional protocols. The medical community in the 1880s realized this lesson as well. A medical critic at the time said, “ If Garfield had been a ‘tough,’ and had received his wound in a Bowery dive, he would have been brought to Bellevue Hospital … without any fuss or feathers, and would have gotten well.â€

Dr. David Kudlowitz is a 3rd year resident at NYU Langone Medical Center

Peer reviewed by Neil A. Shapiro, MD, Editor-In-Chief, Clinical Correlations

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Reference:

Millard C. Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President. New York, NY : Doubleday, a division of Random House; 2011.