Peer Reviewed

After the elementary school shooting in Newtown, CT in December 2012 that left 20 children and 6 adults dead, the country reacted as it had following the July 2012 movie theatre shooting in Aurora, CO, and the public meeting shooting involving Representative Gabrielle Giffords on January 11, 2011 in Tucson, AZ. Some called for tighter firearm safety laws, while others stood by the adage that “Guns don’t kill people,” and that this was no time to politicize a tragedy. The issue of mental health soon followed, with calls for greater awareness and resources directed toward mental health services. While these important issues draw together the realms of healthcare, policy, and legislation, there is another related matter seldom discussed. What role, if any, do physicians play in asking patients about firearms?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 31,347 deaths due to firearms in 2009 [1]. Approximately 60% were suicides, 37% were homicides, and the remainder were accidental shootings.

There were 32,886 deaths due to motor vehicle accidents in 2010, the lowest ever. In fact, motor vehicle fatalities have steadily declined throughout the years. Much of this progress has been accomplished through traffic safety research. As a result, airbags and seatbelts are now required in all vehicles. Data, often collected by physicians at medical visits, spurred educational campaigns and harsher penalties for drunk driving [2]. When it comes to firearms, it’s a different story. National organizations such as the CDC do not analyze gun violence data, since they cannot use federal money to advocate for gun safety and control [3].

Many are familiar with the saying “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” In medicine, we screen for all sorts of conditions in the hope of preventing or ameliorating diseases ranging from hypertension to cancer. We ask personal questions about alcohol and drug use, sexual health and mental health, domestic violence and abuse, suicidal and homicidal behavior. Gun use is a part of that conversation, since suicidal or homicidal individuals with access to guns are more likely to take action [4]. Essentially, we make inquiries about anything and everything that could be health-related.

Physicians have been making recommendations about firearm safety at least as long as an editorial titled “The Indiscriminate Sale of Revolvers,” appeared in the Lancet in 1893 [5]. Presently, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association recommend that physicians inquire about firearms and counsel patients on safety precautions, with individual doctors advocating for discussion as well [6,7]. However, the evidence regarding the efficacy of counseling–mostly conducted in the outpatient pediatric setting–is mixed, with 4 out of 7 trials demonstrating improved storage of firearms [8].

Efficacy aside, what has become a larger barrier and point of controversy is whether or not physicians even have a right to broach the subject. In 2011, a pediatrician in Florida asked one of her patients to find a new physician when the patient refused to answer questions about whether or not she owned firearms. This culminated with Governor Rick Scott signing into law “An Act Relating to Privacy of Firearms Owners.” The bill essentially stated that licensed health care workers were not legally allowed to ask about firearms unless they believed that guns were directly related to the medical issue at hand [9]. A few months later, a U.S. District Court judge granted a preliminary injunction, saying it violated the First Amendment. The state is in the process of appealing the ruling.

Firearm usage and safety are controversial topics in this country. For better or worse, physicians often find themselves injected into these conversations, since we have the ability to affect both individuals and populations with our actions. It’s a question worth discussing: should healthcare workers speak with patients about gun use and counsel them on safety? And, perhaps more importantly, would it have an impact?

Commentary by Antonella Surbone, MD, PhD, FACP, Ethics Editor, Clinical Correlations

Why should healthcare workers not speak with patients or parents about gun use and counsel them on safety? Unfortunately, the topic of gun control involves political and financial interests that seem to go beyond the traditional understanding of “safety” and the physician’s moral and professional duty to make reasonable inquiries on this account.

While our “ability to affect both individuals and populations with our actions” may not always reach as far as we would wish, commitment to life, rather than infliction of suffering or death in all forms, remains a keystone of the medical profession.

Jennifer Zhu is a 4th year medical student at NYU School of Medicine

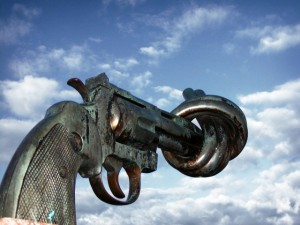

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Peer Reviewed by Antonella Surbone, MD, PhD, FACP, Ethics Editor, Clinical Correlations

References

1. Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Miñino AM, Kung H-C. Deaths: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60(3).

2. Bass JL, Christoffel KK, Widome M, et al. Childhood injury prevention counseling in primary care settings: a critical review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1993;92(4):544–550.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding opportunity announcements; additional requirements. AR-13: Prohibition on use of CDC funds for certain gun control activities. www.cdc.gov/od/pgo/funding/grants/additional_req.shtm#ar13. Accessed December 19, 2012.

4. Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow MJ. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):929-936.

5. The indiscriminate sale of revolvers. Lancet. 1893;141(3626):428.

6. American Medical Association-Medical Student Section. Firearms: safety and regulation. Digest of policy actions: policy number 145.000. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/mss/digest_of_actions.pdf. Updated November 2010. Accessed December 19, 2012.

7. Fleegler EW, Monuteaux MC, Bauer SR, Lee LK. Attempts to silence firearm injury prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):99-102.

8. McGee KS, Coyne-Beasley T, Johnson RM. Review of evaluations of educational approaches to promote safe storage of firearms. Inj Prev. 2003;9(2):108–111.

9. Florida House of Representatives. CS/CS/HB 155: An act relating to the privacy of firearms owners. http://www.myfloridahouse.gov/sections/Bills/billsdetail.aspx?BillId=44993 Accessed December 19, 2012.

5 comments on “Should Physicians Ask Patients about Guns?”

What is unfortunate about this review, although undoubtedly well-meaning, is that it exhibits the usual knee-jerk reaction of someone who is an urban-based young person who has never been exposed to the shooting sports, hunting or the sheer enjoyment of target shooting. What would this 4th year medical student at NYU say if she lived in a rural setting where outdoor sports, including a strong hunting and shooting culture is prevalent, and where it would take a half hour, at best,before the first policeman could arrive in an emergency? It’s very self-satisfying to pontificate about guns from the perspective of someone like her, and impose her narrow views on others!

Instead of putting the onus on the vast majority of sensible, mature and lawful gun owners, how about those in our profession who treat mental illness and fail to raise” red flags” with authorities when they encounter potentially dangerous patients?

A timely article just released by the American College of Physicians:

http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=1860325

I vociferously disagree with the first comment posted above. As a native Texan who did grow up with guns in the home, I do think that it is entirely reasonable to ask patients if they have guns in the home (especially if children are present) and what precautions they have taken to safeguard those weapons. The issue of the medical community’s role in advocating for patient safety when it comes to gun ownership really isn’t (nor should it be) a political, privacy, or even a constitutional concern. Physicians do and should ask about other potential dangers and safety measures in the home, including chemicals, medicines, smoke detectors, seatbelts, helmet use, etc. Only gun ownership is controversial. This discussion between the physician and patient is about promoting patient safety, not taking away anyone’s constitutional rights. We really do need to move behind this “knee-jerk reaction” from gun rights advocates that any question about guns is an attack on the 2nd amendment. We as a society tolerate and encourage healthy dialogues about other constitional liberties, including freedom of speech, religion, the press, and against search and seizure. Why can’t we do that when it comes to guns?

I stick to Ishmeal’s point that patients should be asked if they have guns in their homes and if any precautions were taken. Still, I don’t believe that guns are those to kill people. People kill people. We must treat the cause.

Thanks to our Editor for posting the link to the American College of Physicians’ Policy Position Paper on “Reducing Firearm-Related Injuries and Deaths in the United States”. Please read it in view of our professional responsibilities.

Comments are closed.